Some shrubs produce flowers that do more than draw the eye; they also delight us with their delicious scent. The most obvious examples are hybrid tea roses and common lilac (Syringa vulgaris), which owe a good deal of their renown to the legendary bouquet of their blooms. Yet many other shrubs offer equally alluring fragrance, often at seasons when lilac and rose are at a lull. Here’s a seasonal summary of a few of the best.

Asian Witch Hazels

Asian witch hazels (Hamamelis x intermedia and H. mollis) – The ribbon-like yellow, orange, or red petals of these large shrubs unfurl on mild days in late winter (this year, they started blooming in mid-January here in balmy Rhode Island). Plant Asian witch hazels to the south of paths, doorways, and other winter viewpoints, where their gossamer petals will glow against the slanting rays of the winter sun, and where mild southern breezes will waft the flowers’ lemony scent to passersby. Witch hazels offer a bright encore in fall, their leaves assuming sunset tones that distantly echo the hues of their winter flowers. Hardy from USDA Zones 5b to 9, they succeed in full to partial sun and in just about any soil that’s not soggy or parched.

Winter Honeysuckle

Winter honeysuckle (Lonicera fragrantissima) – A welcome sight and scent in the late winter garden, this East Asian native perfumes the air with small, white, funneled blooms that open on mild days from January to early April. A deciduous, 6-foot shrub in the colder sectors of its zone 5 to 9 hardiness range, it behaves – or rather misbehaves – as a moderately to highly invasive 8- to 12-foot evergreen in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeast. It’s thus best reserved for northern U.S. gardens. Its hybrid Lonicera × purpusii (including ‘Winter Beauty’) does much the same thing. All forms of winter honeysuckle favor full to partial sun and well-drained, average to fertile soil.

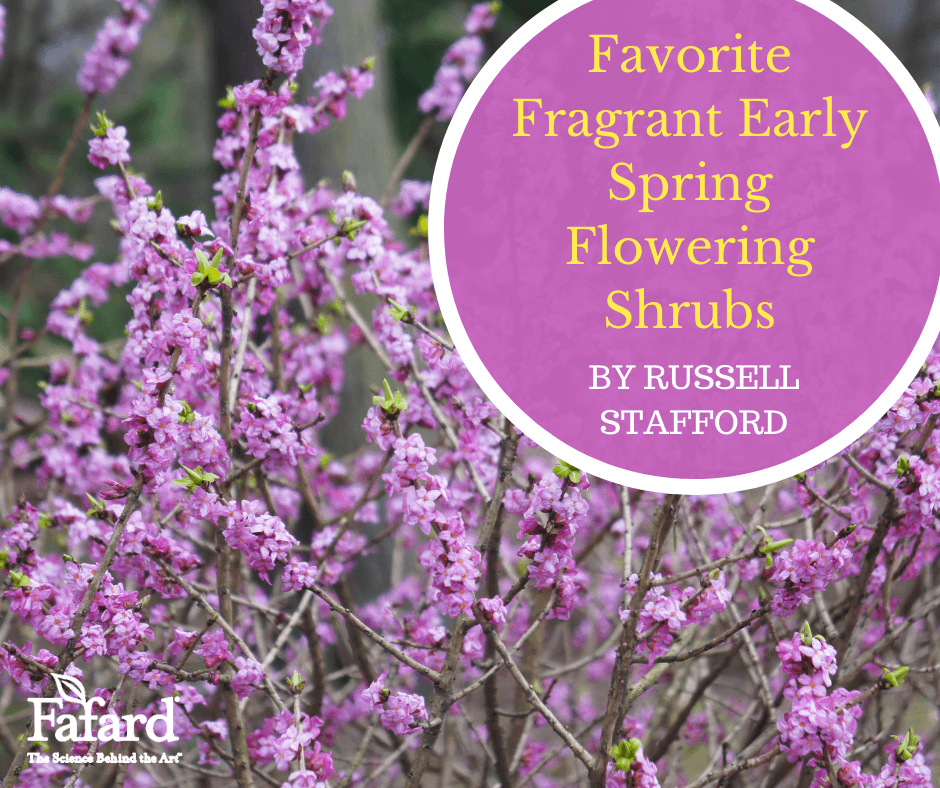

February Daphne

February daphne (Daphne mezereum) – Intensely fragrant mauve-pink flowers crowd the naked, erect branches of this sparse, 3- to 4-foot shrub in late winter and early spring – a bit later than its common name would suggest. White-flowered cultivars are also available. Poisonous red fruits follow the flowers, and sometimes give rise to volunteer seedlings. A long-time garden favorite in its native Eurasia as well as in the U.S. and Canada (where it’s hardy from zones 4 to 7), it does best with plenty of elbow room, humusy well-drained soil, and full to partial sun. Give it a late-spring top-dressing of Fafard® Premium Topsoil to keep its roots cool, healthy, and happy.

Spring-Flowering Viburnums

Korean spice viburnum (Viburnum carlesii) – The searching clove-like fragrance of Korean spice viburnum’s tubular, pinkish-white blooms is a welcome and warming presence in the mid-spring garden. The domed flower clusters typically open around the first of May in USDA Zones 5 and 6. Korean spice’s hybrid Judd viburnum (Viburnum x juddii) offers similar flowers and grayer, less aphid-prone leaves, in a similar, 6- to 8-foot package. The flowers of fragrant snowball (Viburnum x carlcephalum), another carlesii hybrid, are waxier and of heavier substance, and occur in larger, denser, almost spherical clusters. For tighter spaces there’s Viburnum carlesii ‘Compactum’, which matures at about 3 feet. Most forms and hybrids of Korean spice viburnum prosper in full sun from zones 5 to 8, and turn smoky burgundy tones in fall. Fragrant snowball is slightly less hardy, to zone 6.

Korean Abelia

Korean abelia (Abelia mosanensis, aka Zabelia tyaihyonii) — An unassuming shrub most of the year, Korean abelia grabs sensory center stage in mid-spring when it envelops its branches in funnel-shaped pink flowers. The swarms of beguilingly spicy blooms draw every butterfly (and human) within sniffing distance. The flowers also attract hummingbirds, desipite the fact that these birds have little to no sense of smell. This 4- to 6-foot shrub makes a great choice for full sun and average to fertile soil in zones 5 to 9.

Caucasian Daphne

Caucasian daphne (Daphne x transatlantica) — Late spring is also when this little love begins its lengthy bloom season. Wafting a complex and seductive fragrance containing hints of clove and vanilla, the glistening white flowers flush first in May and June, repeating the performance multiple times throughout summer and early fall. No other shrub in the 3-foot range can surpass it for flower power and scent. The variegated cultivar ‘Summer Ice’ compliments the blooms with white-edged leaves. All forms of Caucasian daphne are ideally suited for planting near paths and patios and other areas where their flowers and scent can cast their spell. Full to part sun and humus-rich, well-drained soil is ideal, as is a niche protected from harsh winter wind and crushing snow loads. Plants are hardy from zone 5 to 8.

Summersweet

Summersweet (Clethra alnifolia) joins the fragrance fest in early summer. Its candles of fuzzy white or pink flowers carry a distinctive (and irresistible) scent with root beer undertones. The finely toothed, insect- (and deer-) resistant leaves of this rock-hardy eastern North American native are a lustrous dark green, turning brilliant butter-yellow in fall. Compact cultivars of summersweet (such as ‘Hummingbird’ and ‘Sixteen Candles’) make splendid shrubby ground covers for sun or shade, suckering to eventually cover considerable territory. Full-size, 6- foot varieties such as pink-flowered ‘Ruby Spice’ are among the premier shrubs for the summer garden. All forms do best in moist, humus-rich soil in zones 4 to 8.

Swamp Azalea

Swamp azalea (Rhododendron viscosum) is another summer-blooming native shrub with a wonderful scent (which hints at cloves rather than root beer). It, too, loves moist soil, making it an obvious garden companion for summersweet. Also well worth planting within its zone 5 to 8 hardiness range are several swamp azalea hybrids such as pale-yellow-flowered ‘Lemon Drop’.

Glory-Bower

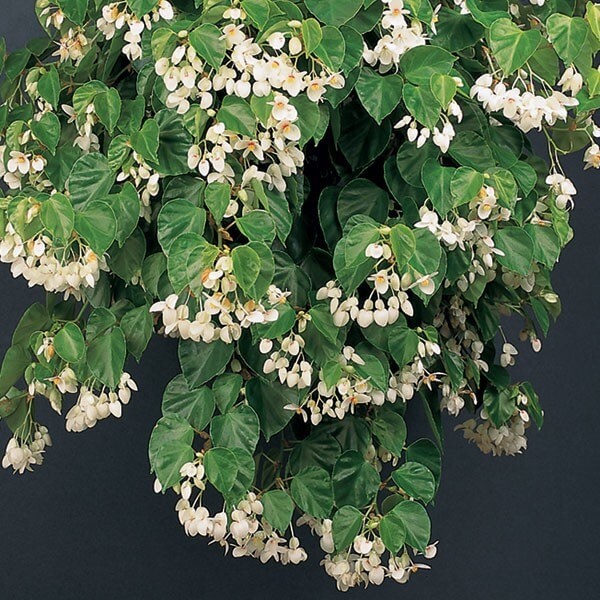

Glory-bower (Clerodendrom trichotomum) — For late-season fragrance there’s this large suckering shrub (which reaches arboreal stature in warmer parts of its zone 6 to 9 hardiness range). The starry pale pink flowers begin in August and continue for many weeks, eventually giving way to blue-black berries nested within showy maroon calyces. This rather rambunctious East Asian native is not for small spaces or for locations where it might invade nearby natural areas (especially in the southern portions of its zone 6 to 9 hardiness range). It tolerates some shade, but prefers full sun.