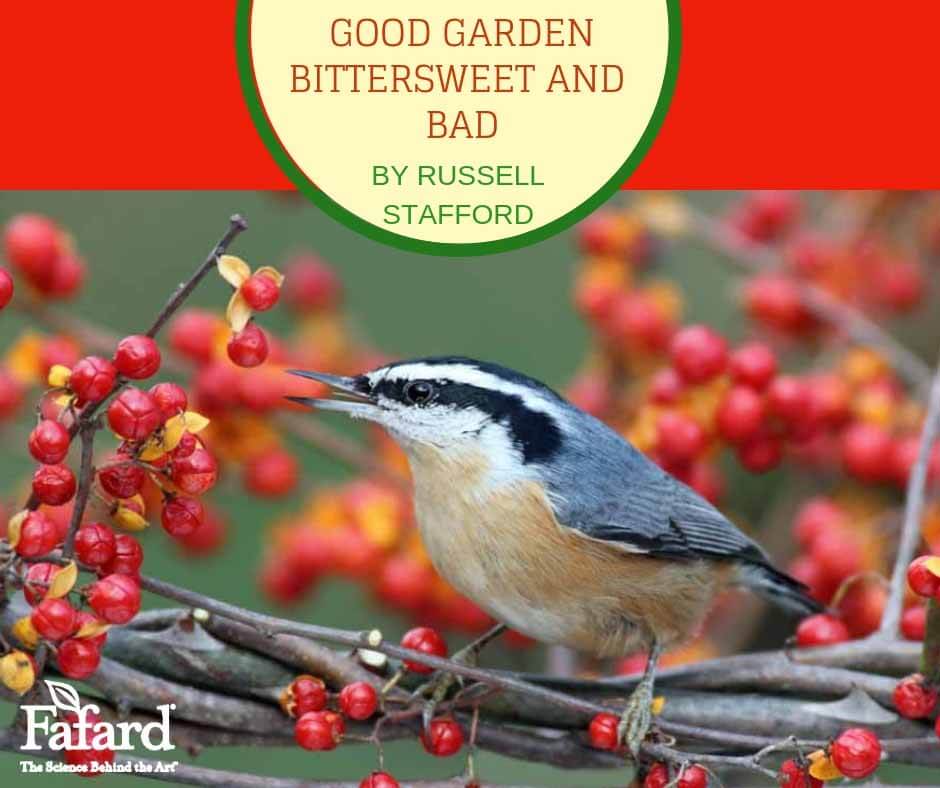

When it comes to garden plants gone wrong, few have gone wronger than oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus). Introduced from East Asia to Western horticulture in the early eighteenth century, this twining vine was widely planted for its ornamental clusters of yellow pea-sized fruits that open in fall to reveal brilliant-red interiors. Now it’s widely reviled for its ability to seed itself everywhere by way of those showy, bird-attracting fruits. Left unchecked, these seedlings can rapidly morph into tree-consuming monsters, smothering everything in their 60-foot reach. Visit just about any garden or woodland in the eastern U.S. and there they are, lurking in the undergrowth or clambering into the canopy.

Good and Bad Bittersweet

This black sheep of the Celastrus tribe has also sullied our attractive and relatively well-behaved native species, Celastrus scandens. The showy orange fruits of American bittersweet are darker in hue than those of its Asian relative, and they appear in elongated bunches at the stem tips rather than in small clusters in the leaf axils. It grows more sedately than Celastrus orbiculatus, self-sows less enthusiastically, and coexists more harmoniously. Ironically, its more restrained growth also puts it at a competitive disadvantage in natural areas, where it is often smothered by its mayhem-making relative. The most apropos response to the rampages of oriental bittersweet is to grow MORE of our native bittersweet – not less.

You can create a refuge for American bittersweet by giving it a sizeable pergola or other structure for its 20- to 30-foot stems to twine around and through. Full sun to light shade and lean or average, well-drained soil are ideal (amend heavy or sandy soils by digging in a couple of inches of Fafard Manure Blend or Premium Natural and Organic Compost). American bittersweet also functions well as a shrubby ground cover for a slope, stone wall, or woodland edge. Plants flower and fruit on the current season’s growth, so pruning is best done in late winter and early spring, before bud-break.

Bittersweet Varieties

Most bittersweet plants bear only male or female flowers, with one of each typically required for fruiting to occur. One male plant (e.g., ‘Indian Brave’) will pollenize as many 10 females (such as ‘Indian Maiden’ and ‘Diana’). Two recently introduced cultivars – ‘Autumn Revolution’ and ‘Sweet Tangerine’ – are self-fruitful, requiring no companion. You can also purchase or grow unsexed seedlings. If so, plant several to increase the chances that at least one is a female. You can remove any superfluous males after they reach flowering size.

Harvest the inedible fruits for holiday decorations after their husks begin to split open in late fall. They make a dramatic addition to a Thanksgiving centerpiece or a Christmas wreath. You’ll also feel considerable satisfaction and pride knowing that they come from our beleaguered and deserving native bittersweet, rather than from its roguish, woodland-consuming cousin. To double down on your sense of satisfaction, leave some fruits so that the robins, mockingbirds, flickers, yellow-rumped warblers, ruffed grouse, and other native birds can share in the delight – and distribute the seed.