Back when one-size-fits-all gardening was a thing, ground covers for shade were seemingly as easy as one-two-three: creeping myrtle (Vinca minor), English ivy (Hedera helix), and Japanese spurge (Pachysandra terminalis). That is before they all began invading wildlands. All were neatly arrayed under an equally ubiquitous Norway maple or Bradford pear– both equally invasive and troublesome.

It was bound to happen. Introduce lots of vigorous, spreading plant species, and you increase the likelihood they will become pests themselves by invading local native plant communities. It did not take long for all three non-native, go-to ground covers to be added to the invasive plant lists of many U.S. states, particularly in the American Southeast and Northwest.

Unfortunately, going ubiquitous presented additional problems in the garden. As anyone who has ever tried to maintain the “perfect” lawn and garden can attest, mass plantings are easy pickings for mass invasions of pests and diseases. Japanese spurge loses a lot of its allure when it’s riddled with Volutella blight, as is all too common these days.

Well-Mannered Groundcovers for Shade

Fortunately, excellent (and arguably superior) ground cover alternatives abound, many of them native. Feeding the soil with quality compost, such as Fafard Premium Garden Compost Blend, at planting time will encourage good establishment from the start.

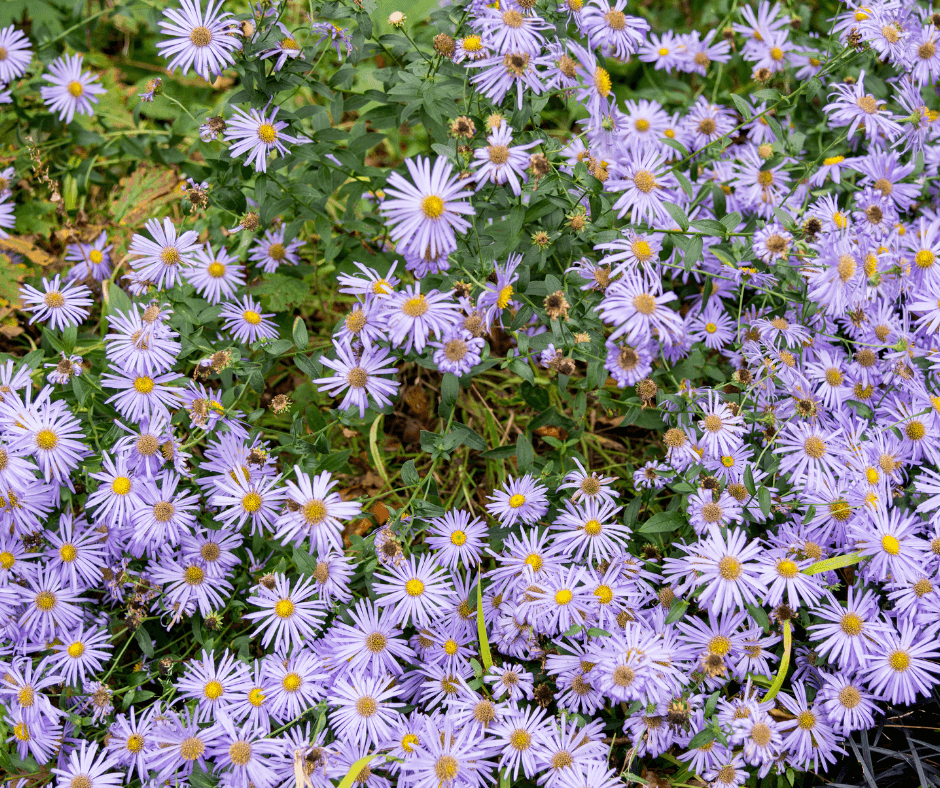

Twilight Aster

Who says ground covers have to hug the ground? Some situations call for something taller. Twilight Aster (Aster x herveyi ‘Twilight’ (aka Eurybia x herveyi)) spreads by rhizomes into large swards of broad-leaved rosettes that give rise in summer to leafy 2-foot-tall stems. Plants are crowned with clusters of pale lavender flowers for many weeks in late summer and fall. An incredibly adaptable thing, ‘Twilight’ can handle situations from dry shade to damp sun. This eastern U.S. native goes dormant in winter.

Sedges

Botanically speaking, they’re not grasses, but sedges provide much the same look for shade with their clumps of narrow-bladed leaves. Masses of low sedges such as Carex pensylvanica and Carex rosea (both eastern U.S. natives) make excellent low-foot-traffic lawn substitutes. For a bolder look, try a clump of seersucker sedge (Carex plantaginea), whose strappy puckered evergreen leaves contrast effectively with lacier shade subjects such as ferns.

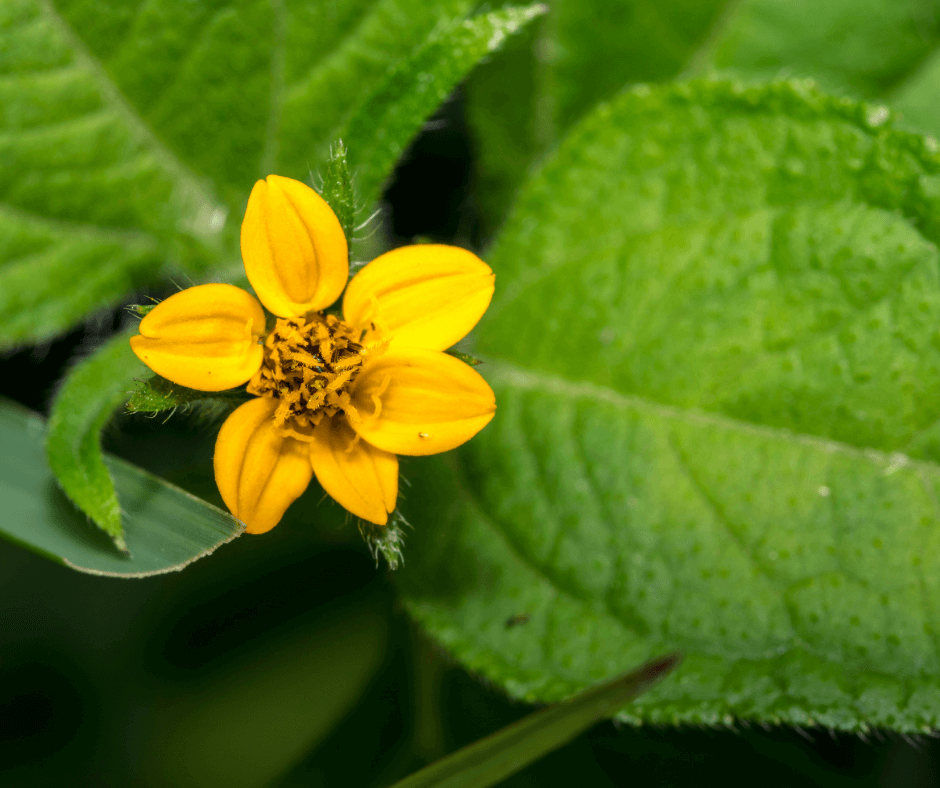

Green-and-Gold

Green-and-gold (Chrysogonum virginianum) is a hardy, attractive woodland native. “Green” references the dense spreading rosettes of fuzzy, crinkled, heart-shaped leaves that hold their color and substance through much of winter. The “gold” is provided by the numerous little yellow “daisies” that spangle the plants in spring and repeat sporadically until fall. Native to woodlands in the Southeast U.S., Chrysogonum virginianum is hardy well north of that, to Zone 5.

Robin’s Plantain

Often occurring as a rather doughty lawn weed, this plantain (Erigeron pulchellus) is a nearly evergreen eastern U.S. native that occasionally assumes much more pulchritudinous forms. The cultivar ‘Lynnhaven Carpet’, for example, grows into handsome carpets of broad fuzzy gray-green leaves that are decorated in spring with pink daisies on 18-inch stems. It’s one of those rare plants you can plug into the garden just about anywhere – sun or shade. Another delightful selection of robin’s plantain is ‘Meadow Muffin’, with contorted leaves that give its rosettes a bit of a cow-pie look.

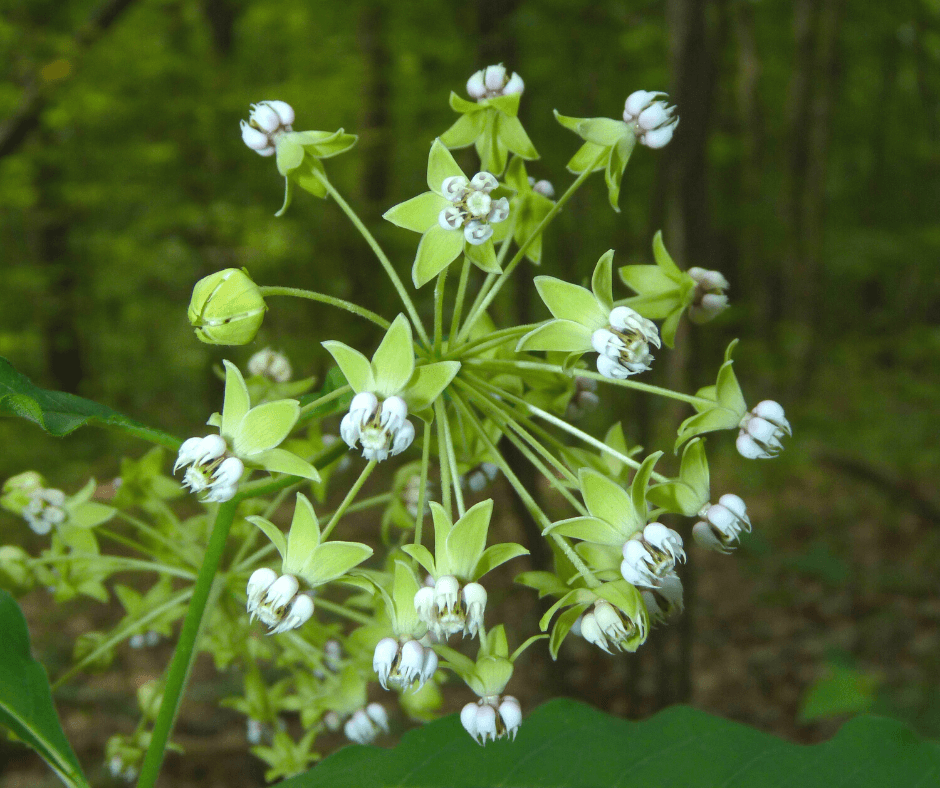

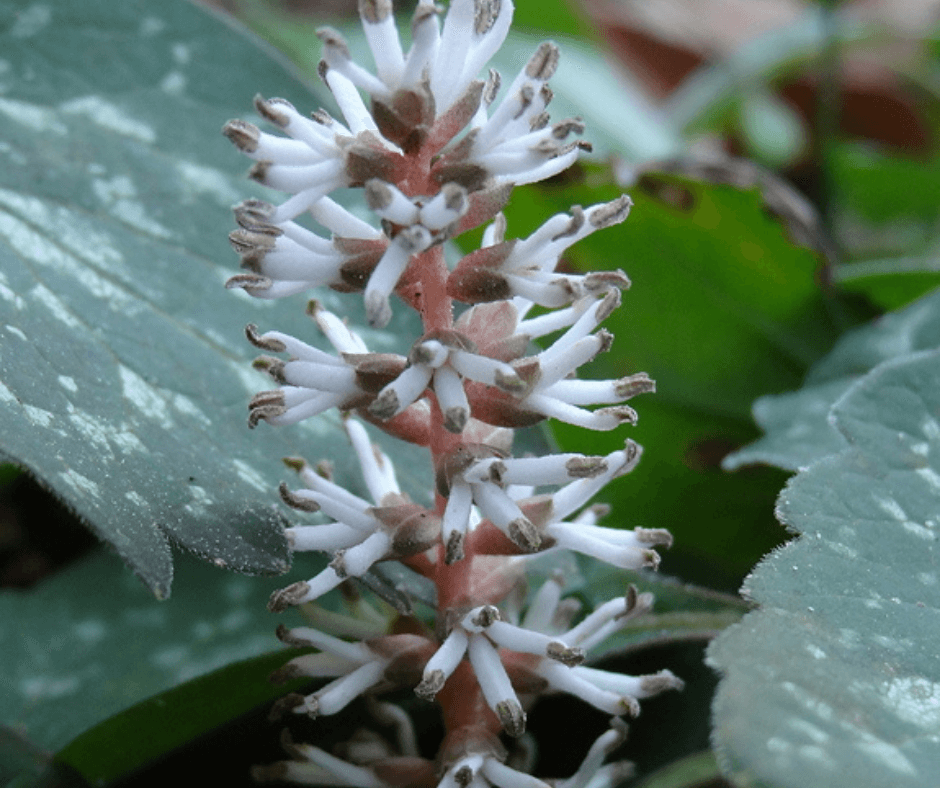

Allegheny Spurge

Although not a rapid runner like the aforementioned Japanese spurge, our Southeast native Allegheny spurge (Pachysandra procumbens) far outdistances it as a desirable ornamental. The whorled evergreen leaves – arrayed in mounded 6-inch-tall clumps – are elegantly splashed with silver mottling, lending the plant a distinguished look totally lacking in Pachysandra terminalis. Things get even splashier in spring when conical clusters of frilly white flowers push from the ground, along with the fresh-green new leaves, as the previous year’s foliage fades. It’s one of those early-season garden scenes that makes your heart leap up. Allegheny spurge thrives in moist humus-rich soil, so give it a dose of Fafard compost if your soil is overly sandy or heavy.

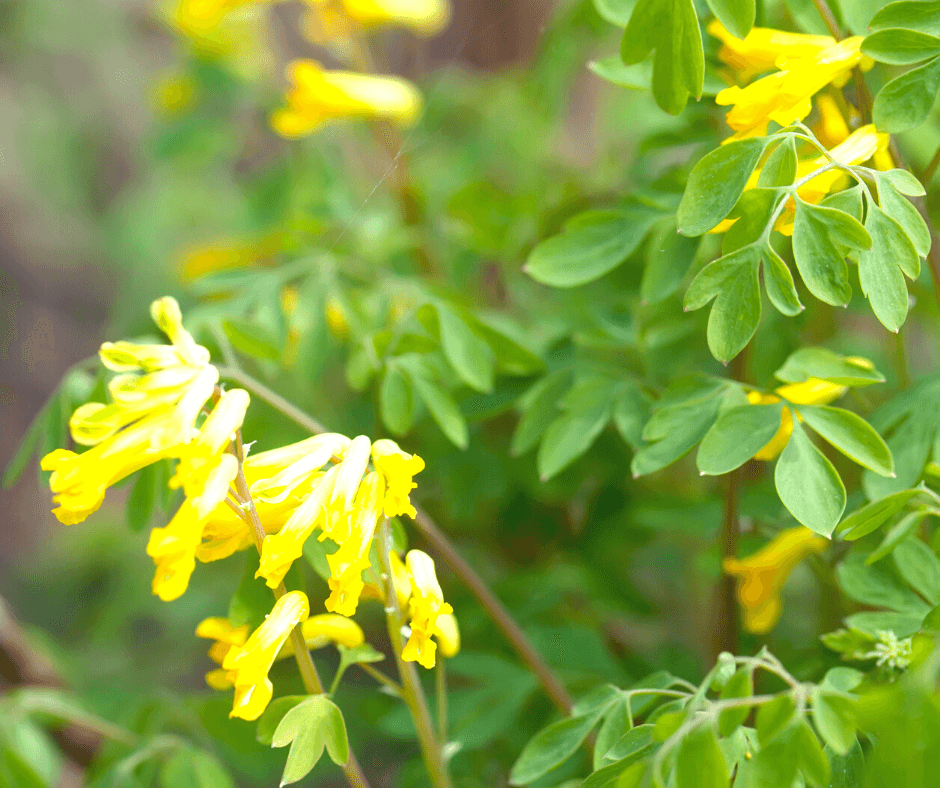

Ragwort

Golden ragwort (Packera aurea) and its near look-alike roundleaf ragwort (Packera obovata) provide quick cover for more informal garden areas. Low swaths of bright green rounded leaves emerge from their rapidly spreading roots in early spring, followed a few weeks later by heads of small yellow “daisies” on 2-foot stems. Use golden ragwort in moist garden situations, and roundleaf ragwort in moist to dry niches. They’re both native to much of central and eastern North America.

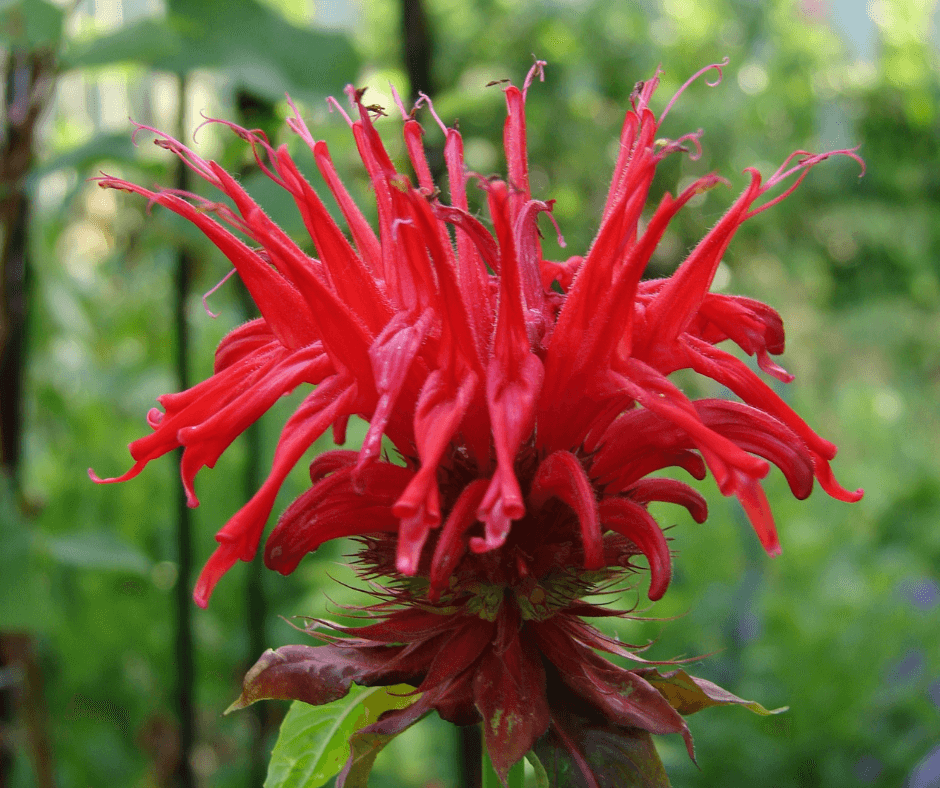

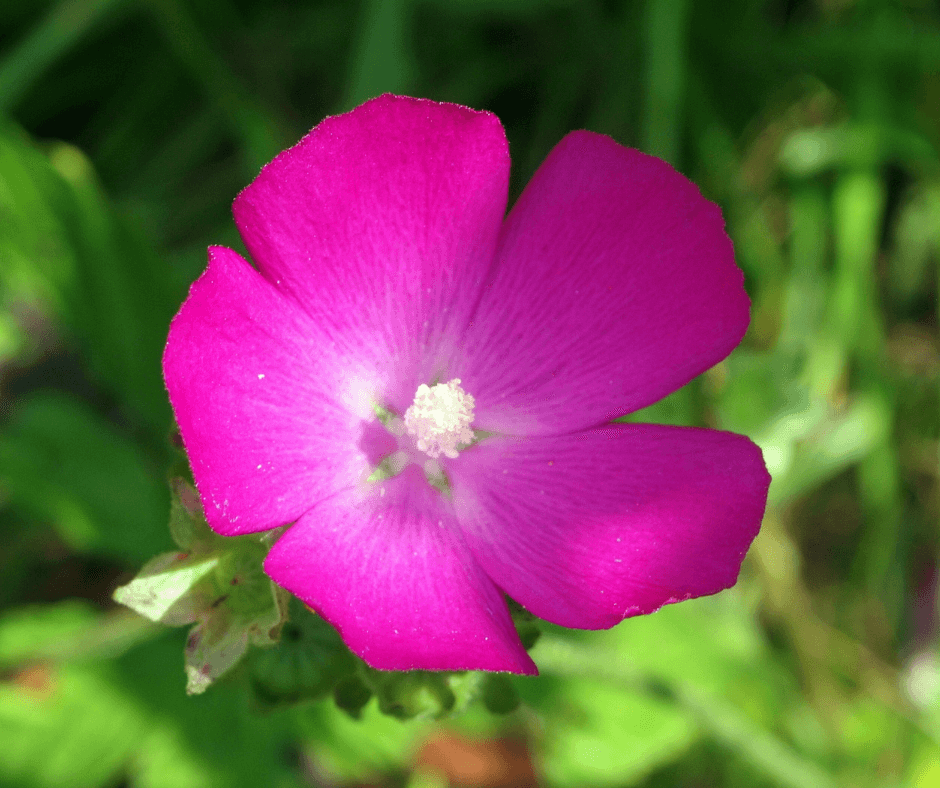

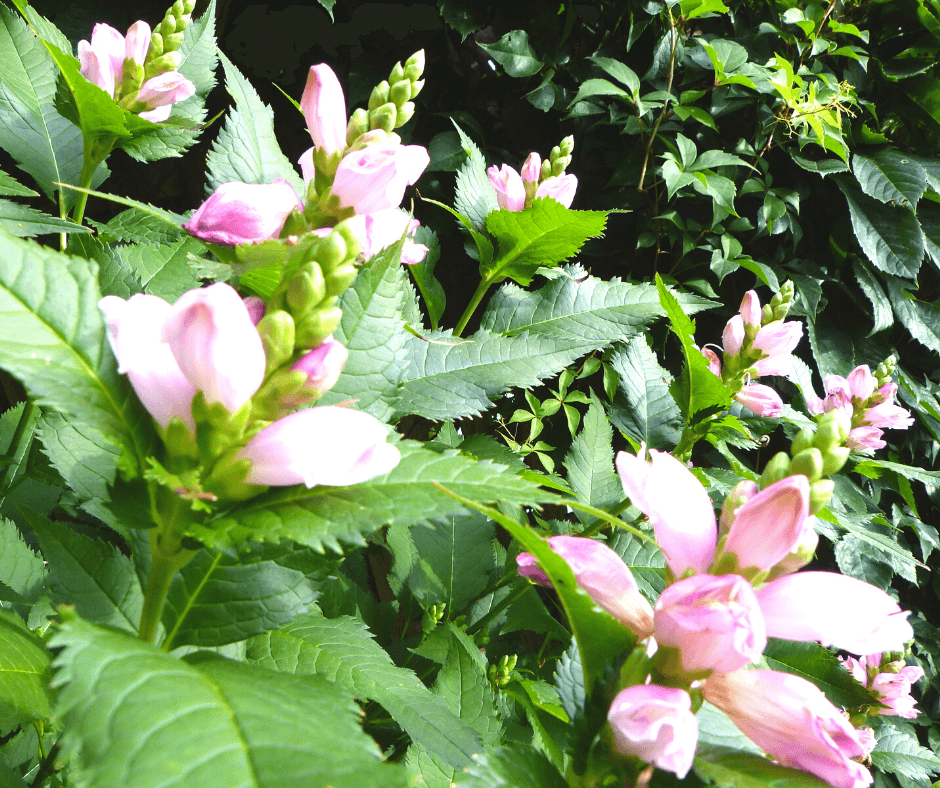

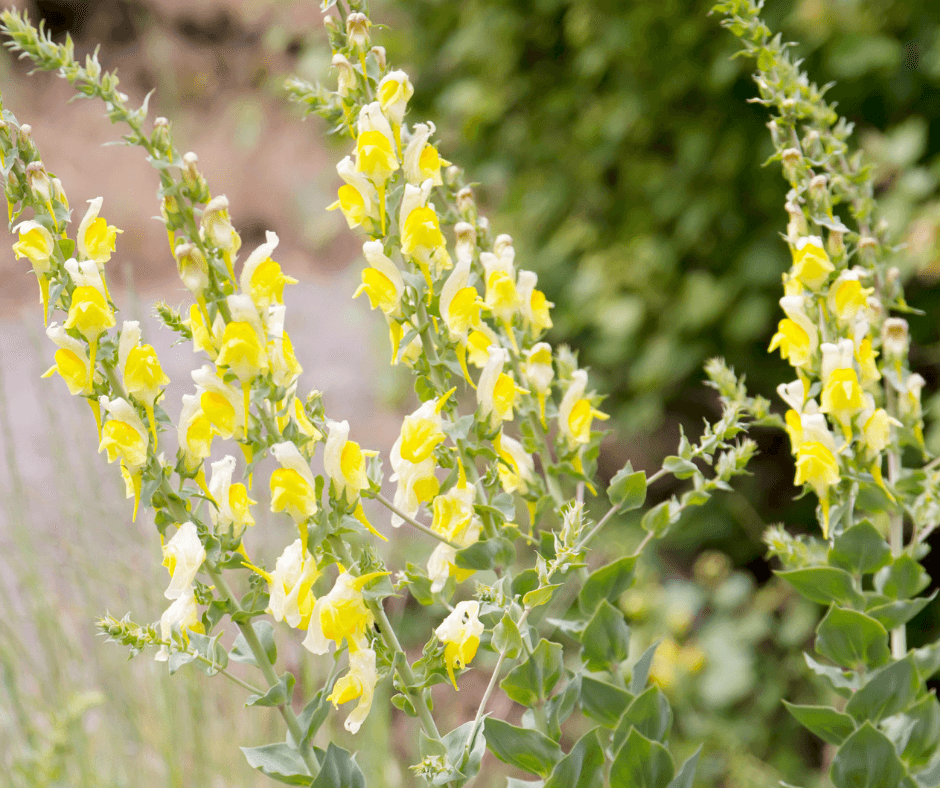

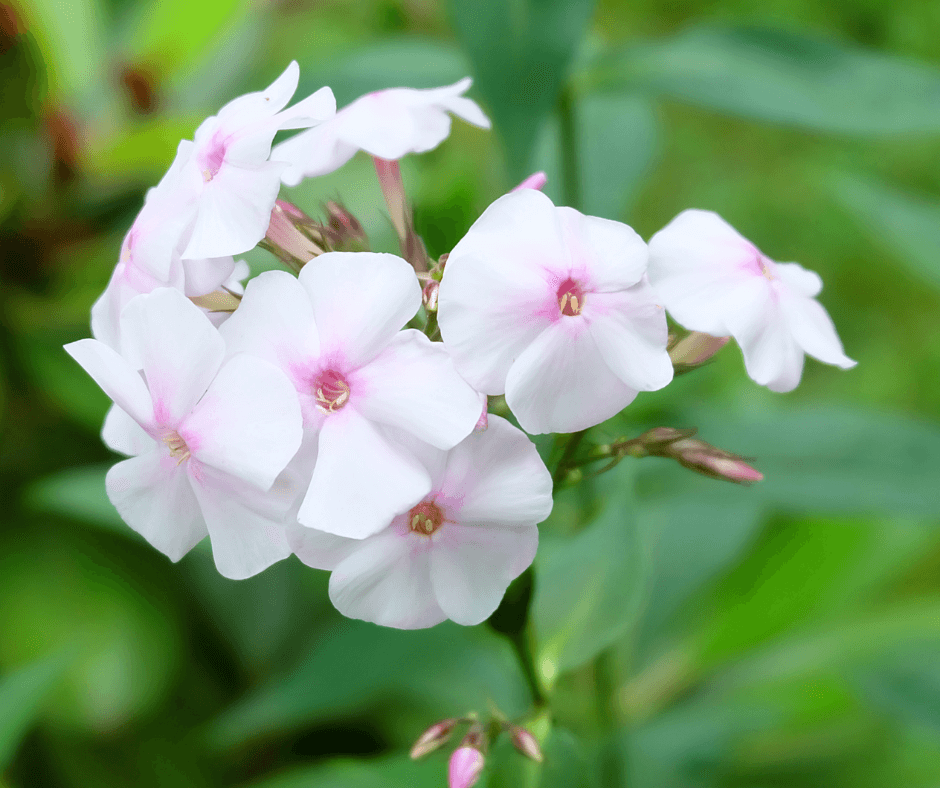

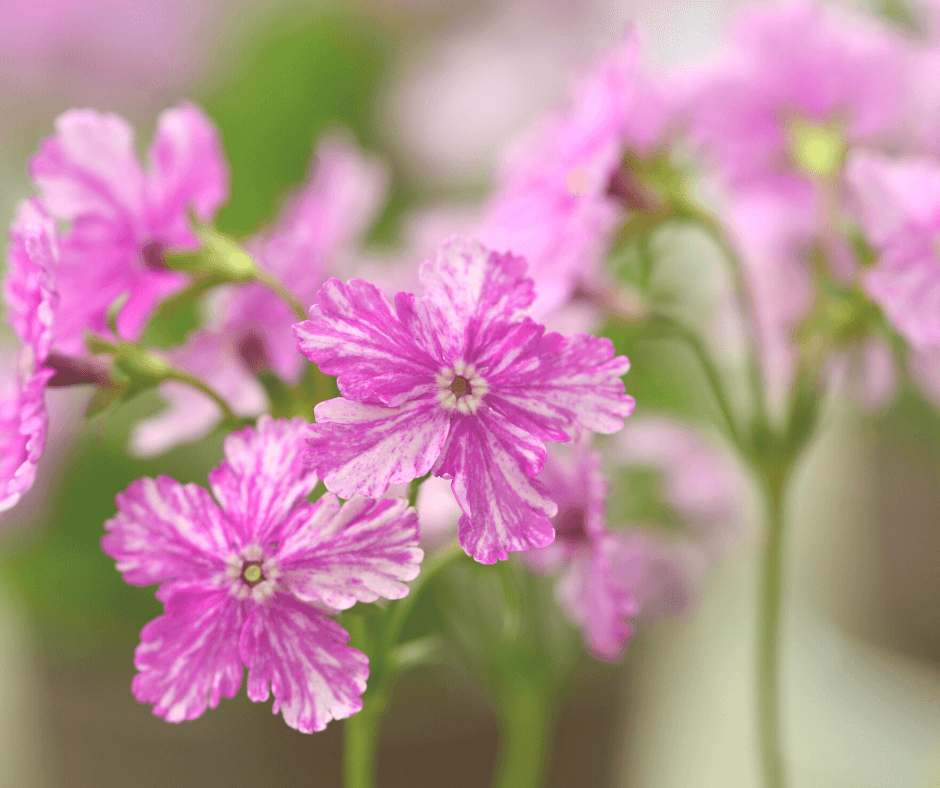

Creeping Phlox

Don’t let its rather dainty appearance deceive you: this evergreen woodland creeping phlox (Phlox stolonifera) from eastern North America will expand into a ground-hugging carpet of small spoon-shaped leaves. It also provides a spring garden highlight when it opens its clusters of proportionately large round-lobed flowers, poised on 6-inch stems. Blue-, pink-, violet-, and white-flowered selections are available, but probably the best for ground cover is the vigorous cultivar ‘Sherwood Purple’.

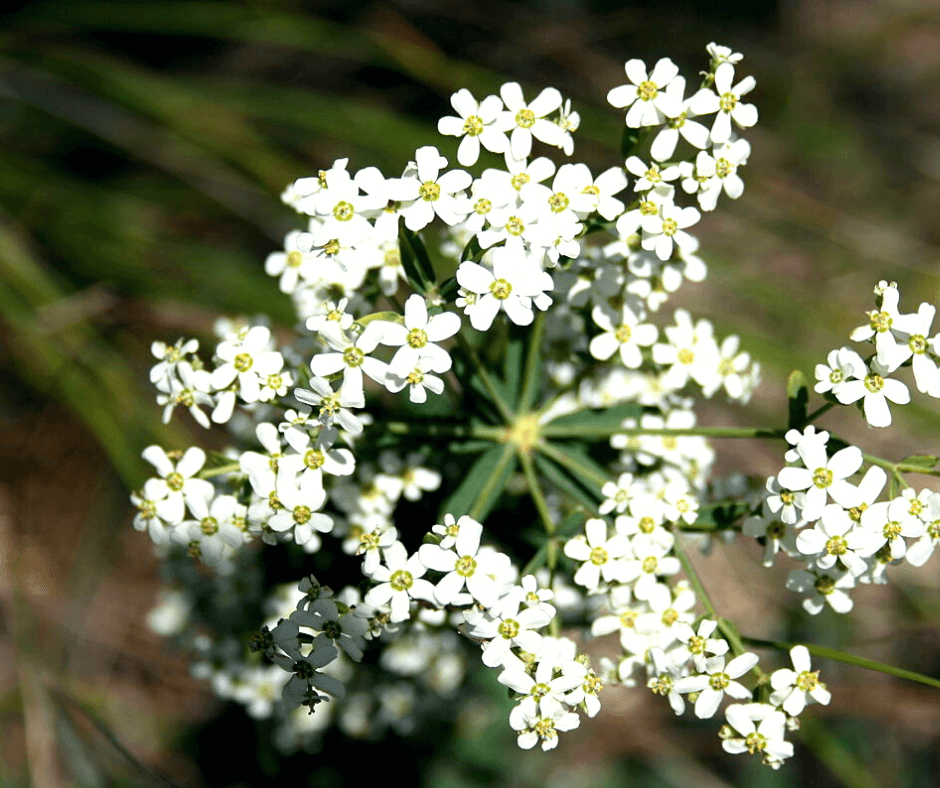

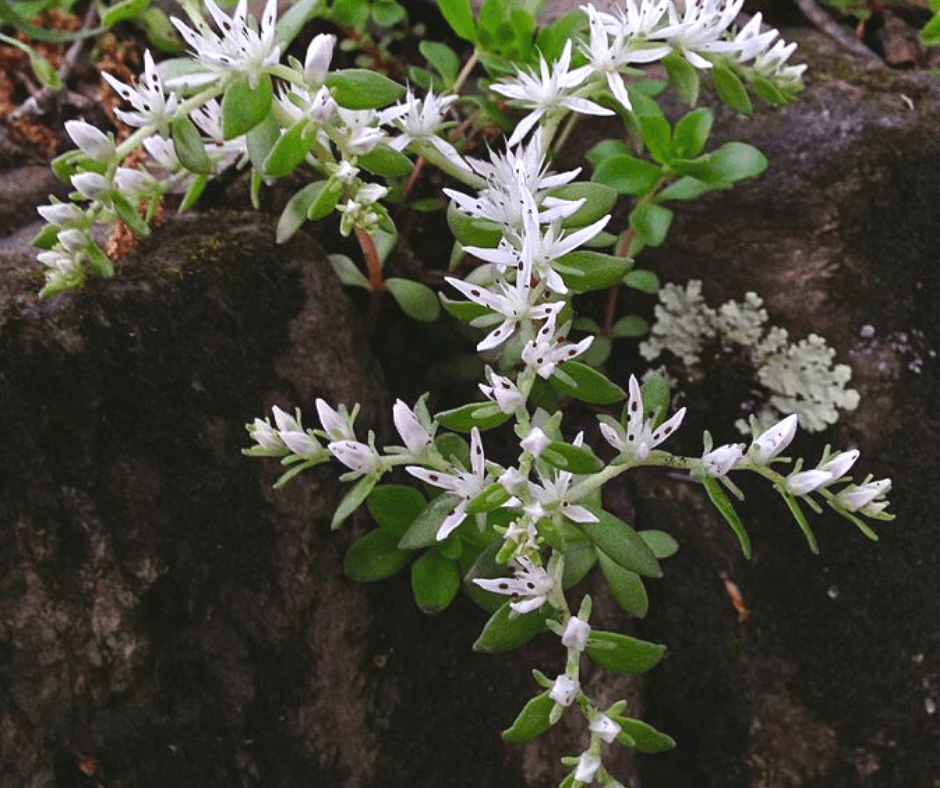

Whorled Stonecrop

If you think stonecrops are drought-loving sun plants, you’re probably not acquainted with Sedum ternatum. Hailing from moist partly shaded habitats over much of central and eastern North America, it makes an excellent small-scale ground cover in similar garden conditions, although it also succeeds in sunnier, drier sites. Its dense low hummocks of fleshy ear-shaped leaves are studded with sprays of white flowers in spring. This highly effective shade plant is still rather rare in gardens – perhaps because of its family associations.

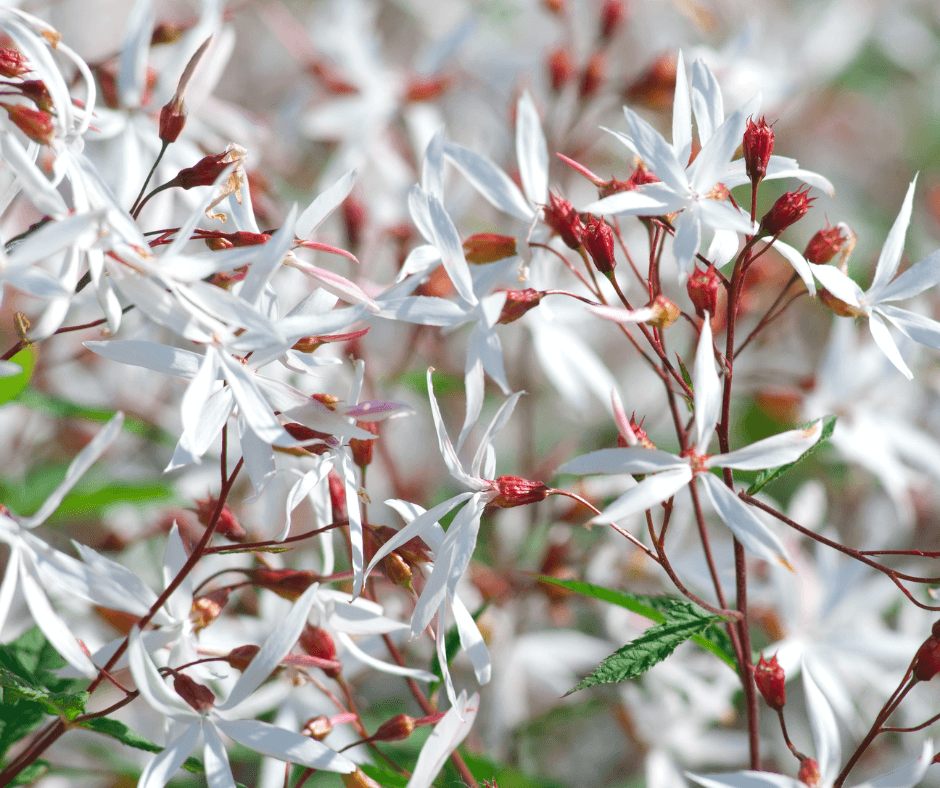

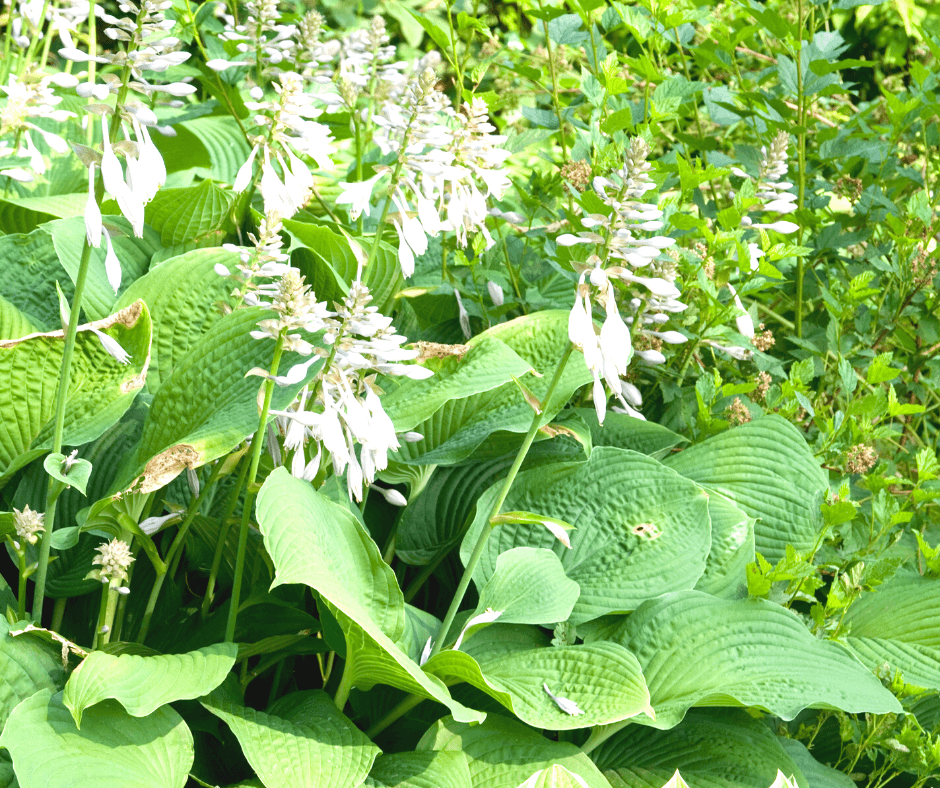

Foamflower

Frothy 6-inch spikes of white flowers appear in spring above spreading expanses of handsome maple-shaped basal leaves. These features of foamflower (Tiarella cordifolia), combined with a tough constitution, make for one of the best and most popular native ground covers for easter U.S. gardens. Its variety collina is a clumper rather than a runner, so it’s a better choice where a less rambunctious ground covering plant is required.

Barren Strawberry

Dense swaths of strawberry-like leaves expand steadily and tenaciously to provide attractive semi-evergreen ground cover in most any garden niche, from dry shade to full sun. Saucer-shaped yellow flowers dot the plants in spring, with a few repeat blooms later on. Recently moved to the genus Geum, barren strawberry (Waldsteinia fragarioides aka Geum fragarioides) is one of the best native ground covers for eastern U.S. gardens – under whatever name.