Midsummer is a hot time in the perennial garden. This is true not only of the weather, but also of the flowers that hold sway at this season. Rudbeckias (featured here last month), sunflowers, coreopsis, heleniums, goldenrods, bee balms, and numerous other large perennials with hot-colored flowers reach their peak from July into September, saturating the garden with their dazzling hues.

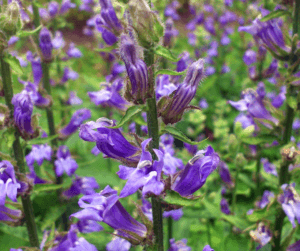

Blue-flowered perennials that bloom in summer make a refreshing, cooling contrast to these dominating fiery hues. Their relative rarity has led to near-overuse of several of them including English lavender (Lavandula angustifolia), hybrid sage (Salvia x sylvestris), spiked speedwell (Veronica spp.), and Persian catmint (Nepeta racemosa). The ranks of blue-flowered perennials include quite a few other excellent choices, however.

Spark’s and Bicolor monkshoods (Aconitum ‘Spark’s Variety’; Aconitum ‘Bicolor’)

Literally a midsummer standout in full to part sun and rich moist coolish soil, ‘Spark’s Variety’ sends up stately branching clusters of deep violet-blue, helmet-shaped flowers in July and August. The 4- to 5-foot stems sometimes need staking. The variety ‘Bicolor’ owes its name to its two-tone violet-blue and white flowers, borne on 40-inch stems at about the same time as those of ‘Spark’s Variety’. As with all monkshoods, they do best in areas with relatively moderate summers in USDA Hardiness zones 3 to 9, and suffer in hot humid conditions. Handle monkshood roots and other parts with caution: they contain potent toxins that make them a potential risk, especially in proximity to children, pets, or edible plants.

African lily (Agapanthus spp.)

Some cultivars of these southern African natives are remarkably hardy, wintering in USDA Zone 6 (or even 5) under a thick coarse mulch (such as oak leaves). Among the hardiest are the selections ‘Galaxy Blue’ and ‘Blue Yonder’, which bear rounded clusters of blue trumpet-shaped flowers from early- to mid-summer on upright 3-foot stems. Other hardy cultivars include white-flowered ‘Galaxy White’, as well as a group of blue- and white-flowered variants that go under the collective name ‘Headbourne Hybrids’. The clumps of strap-shaped basal leaves are also ornamental. Hardy species have deciduous foliage, whereas most cold-tender Agapanthus are evergreen, qualifying them as four-season houseplants (or garden subjects, where suitable). Deciduous varieties can be dug and stored bare-root over winter.

Anise hyssop (Agastache spp.)

The eastern U.S. native Agastache foeniculum provides a summer-long display of lavender-blue spikes atop 3- to 4-foot stems. Pollinators of all sorts swarm the flowers.

Its anise-scented and-flavored leaves contribute to the edible garden as well, making a spicy addition to salads and stir-fries. An enthusiastic self-sower, anise hyssop will happily seed itself about the garden, if allowed. Hybrids between anise hyssop and its East Asian relative Agastache rugosa tend to be sterile (no seedlings) and relatively compact; these include ‘Blue Fortune’, ‘Black Adder’, and ‘Blue Boa’. They’re also a bit less hardy than Agastache foeniculum, to USDA Zone 5 rather than 3. All agastaches do best in sunny, well-drained garden niches.

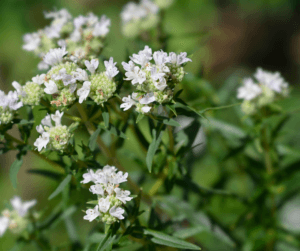

Calamint (Calamintha nepeta)

Hazy swarms of small pale blue or white flowers hover above low mounded clumps from early summer until frost. The headily mint-scented leaves of this sun-loving perennial flavor many traditional dishes in Italy, where the plant is known as nepitella or mentuccia. Calamint also makes for an excellent mojito. It’s ideal for massing in perennial plantings, or for dressing up vegetable and herb gardens. Plants are hardy from zones 4 to 10.

Plumbago (Ceratostigma plumaginoides)

Few ground covers are as colorful as plumbago. Scatterings of deep sky-blue, rounded flowers spangle its spreading, foot-tall stems beginning in summer. Bloom continues into fall, as the foliage turns showy wine-red hues. Happiest in sunny, well-drained sites in hardiness zones 5 to 10, plumbago also accepts a modicum of shade. Shear plants back in late fall or early spring.

Tube-flowered clematis (Clematis heracleifolia)

A total departure from the large-flowered, vining hybrids by which many gardeners know clematis, this large shrubby perennial produces clusters of fragrant, tubular blue blooms in mid- to late summer. The 3- to 4-foot stems sprawl rather than climb, typically requiring staking. Selections and hybrids of the subspecies davidiana (including the cultivar ‘Wyevale’) are distinguished by their showy, wide-flaring flowers that appear a bit earlier in the season than those of the straight species. Sun to partial shade, good well-drained soil, and relatively mild zone 3 to 9 summers suit all forms of the species best. Plants will be especially happy if you give them a spring mulching of Fafard® Premium Natural & Organic Compost.

Great blue lobelia (Lobelia siphilitica)

Also oxymoronically known as blue cardinal flower, this central and eastern North American native is a close cousin and compatriot of the incandescently red-flowered Lobelia cardinalis. It’s a more adaptable and long-lived garden plant than its scarlet relative, however. Give it a moist to dryish, sunny to partly shaded location and just about any type of soil and it will bring forth its 3-foot candelabra spires of mid-blue flowers in July and August. When not in bloom, it retreats to a low rosette of gently toothed, tongue-shaped leaves. After a year or two, you’re likely to have several more such rosettes and spires, thanks to self-sowing.

Russian sage (Perovskia spp.)

The aromatic grayish-green foliage and slender spires of violet-blue flowers of this shrubby perennial give it something of the feel of an oversized lavender. The individual leaves are broader and more toothed than those of lavender, however, and the flowers come somewhat later in the season, from July to October. Perovskia atriplicifolia – the prototypical Russian sage – ascends (to more than 4 feet tall, but numerous more compact hybrids and varieties are available. These include ‘Blue Spritzer’, which flowers prolifically on 30-inch stems with oval, untoothed leaves; ‘Little Lace’, with relatively deep-hued blooms and finely divided leaves on 32-inch plants; and ‘Denim ’n Lace’, an especially showy 32-inch-tall selection that features deeply toothed leaves and 24-inch spikes of relatively dark-hued purple flowers. Russian sage thrives in sun and lean soil. Plants should be cut back to a few inches from the ground in spring, before leaf-break.

Balloon flower (Platycodon grandiflorus)

Inflated flower buds that do indeed resemble miniature balloons open to cupped 5-pointed flowers in early summer. Typically purple-blue, they also come in white, pink, or a variegated mix of these colors. The buds of a few varieties such as ‘Komachi’ do not open, remaining as balloons. Flowering occurs atop clustered upright 30-inch stalks that arise from tuber-like roots relatively late in spring. Dwarf varieties such as 10-inch-tall ‘Apoyama’ are also available. Balloon flowers make good subjects for well-drained, sunny to partly shaded niches in zones 3 to 10.

Downy skullcap (Scutellaria incana)

This native of dry woodlands and other challenging habitats in the central and eastern U.S. is undoubtedly one of the best and most overlooked blue-flowered perennials for sunny to partly shaded sites in those regions and beyond (zones 3 to 9). Branching clusters of tubular, two-lipped, mid-blue flowers ornament the garden for many weeks starting in early summer, attracting bumblebees and hummingbirds. They occur on erect, 3-foot-tall plants, with self-sowing often occurring.