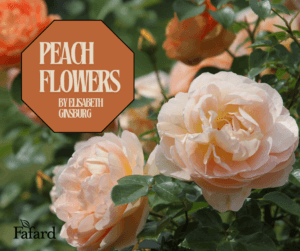

Every year the color specialists at Pantone select a “color of the year”. For 2024 the color is “Peach Fuzz”, a soft yellow/orange shade that conjures images of ripe fruit and summer sunsets. The “fuzz” part adds homey, comforting associations.

In the garden peach is a good companion, harmonizing with shades of white, blue, green and even certain pinks. Even though the Pantone “Peach Fuzz” is a defined hue, peach flowers and foliage can run the gamut from pale tones to shades that are close to coral. Peachy blooms are popular with florists and frequently makes trips up the aisle in brides’ hands

Spring into Peach

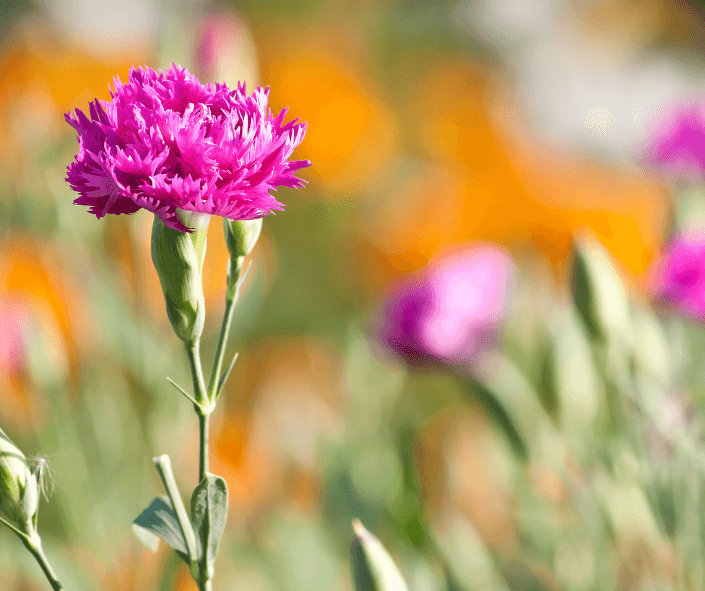

Peach starts the garden year with a bang. Some of the “pink-cupped” daffodils, like the heirloom variety ‘Mrs. Backhouse,’ actually bloom in peach tones (depending on soil and light conditions). Real peach thrills sprout with the tulips, like the much loved Triumph tulip ‘Apricot Beauty’ that boasts large blooms and tall stems. Later in spring, the peachy drama amps up with varieties like the late spring flowering ‘Stunning Apricot’, which blooms in a slightly more saturated shade. Fragrance lovers can revel in ‘Gypsy Queen’, a hyacinth that has been transmitting peachy garden vibes since its introduction in 1927. If you have the space, invest in a flowering quince bush like the ‘Peach’ variety that is part of the Double Click® quince series. Mature quinces cover themselves in blooms, delighting bees and humans.

Summer Daisies

Early summer is daisy time, and the daisy clan is full of choice peaches. The annual cosmos ‘Apricotta’ has an almost ombre quality, with peach petals shading to pink. Many coneflowers (Echinacea) bloom in peachy hues, but the appropriately named ‘Apricot’, a single-flowered variety that is part of the Fresco™ series, with gray-green foliage and non-fading color.

The tickseed or coreopsis range has expanded almost exponentially of late, and includes the threadleaf variety, ‘Crème Caramel’, which is not really caramel-colored, but peachy-pink.

In the shade garden the double impatiens ‘Ole Peach’ lightens things up with pert little blooms that work at border edges, containers and window boxes.

Daisies, including the peachy ones, thrive on sunshine, consistent moisture and a good soil amendment like Fafard® Premium Natural and Organic Compost.

Peachy Leaves and Shady Business

In shady situations, peach tones can come in the form of tall foxgloves like Digitalis ‘Dalmatian Peach’. The plants are generally biennial, but if you let them, they self-seed regularly. For spots that are both damp and somewhat shady, feather astilbes, like ‘Peach Blossom’ fill the bill.

For foliage color that spans the seasons and stands out in the shade, try shade-tolerant varieties of perennial coral bells (Heuchera) like compact ‘Peach Flambe’ and ‘Peachberry Ice’. Both bear dainty spring flowers on tall, slender stems, but the leaves, which are opulently ruffled, are the real attraction. Heucheras also have neat mounding habits making them good team players in the garden.

Climbing to the Sky

Sometimes space it at a premium and climbing plants are a great answer. ‘Giant Peach Sunrise’ mandevilla, part of the Sun Parasol® series climbs between six and 10 feet in full sun or very light shade. It is frost tender, but makes a splash during the growing season. Black-eyed Susan vines (Thunbergia), are easy-to-grow annual climbers that also paint walls and supports in peachy colors.

What About Roses?

The universe of peach-tinted roses seems to grow every year. David Austin’s ‘The Lark Ascending’ is medium peach with a loosely cupped flower form, while his ‘Roald Dahl’ is a more intense shade. ‘Oh Happy Days’™ is a soft, eye-catching hybrid tea, and ‘Peach Profusion’ offers pointed buds and a multitude of blooms on a floribunda shrub. If landscape or groundcover roses are more your style, you can count on ‘Peach Drift’® roses that grow only about two feet tall and 1.5 feet wide. The Knock Out® rose family has taken the garden world by storm, and includes ‘Peachy Knock Out’® among its members.

Fall Fancies

Dahlias, once thought to be old hat, are now riding a wave of popularity, with peach-flowered varieties available in a range of flower forms and levels of color intensity. Daisy-like ‘Apple Blossom’ is on the yellow end of the peach spectrum, while the pom pom-type, ‘Amber Queen’ offers a more saturated color that is closer to orange. Low-growing ‘Easy Duzzit’ is a collarette variety, with peach shadings. It is perfect for smaller scale displays in containers.

Perennial garden chrysanthemums, long among gardeners’ favorites are distinct from the “hardy” varieties that are widely available in stores in fall. Once planted, the garden types return and flourish for years. Some of the peachiest varieties include daisy-flowered ‘Mary Stoker’, which opens in yellow tones, but ages to peach. ‘Chiffon’ is a cushion mum with petals that shade from pale at the tips to rosy peach at the centers of the flowers. It truly shines in a sunny fall border and helps close out the gardening season on a cheerful note.

The season for fresh peach fruit is short, but in the garden, the peach season provides a ready supply of delectable treats throughout the growing year.