Flower bulbs, water, and a vase (or two) are all you need to bring a splash of spring to your windowsill this winter. It’s as simple as plant-growing gets. The water provides moisture for the bulbs’ roots. The vase provides a container for the water and support for the bulbs’ stems and leaves. And the bulbs take it from there. Everything’s inside these miraculous little plants-in-a-package: the buds, the roots, and the stored food that fuels roots and top growth. Give them the proper stimulus, and they’re off and blooming – no soil required, in many cases.

Paperwhites

Simplest of all are paperwhite narcissus, which require nothing more in the way of stimulus than a hit of water. Place several of them at the bottom of a bubble vase (illustrated) or a tall cylindrical glass vase (6 inches wide by 10 inches deep is an ideal size). Add around an inch of water (don’t worry – they’ll be fine). Move the vase to a cool dimly lit location. Finally, bring the vase out into cool full light when the bulbs begin to push roots. Re-water when necessary. In 3 to 5 weeks, you’ll have paperwhite blooms, their stems neatly propped by the sides of the vase. To further counteract flopping, amend the water with a touch of alcohol, which promotes compact growth.

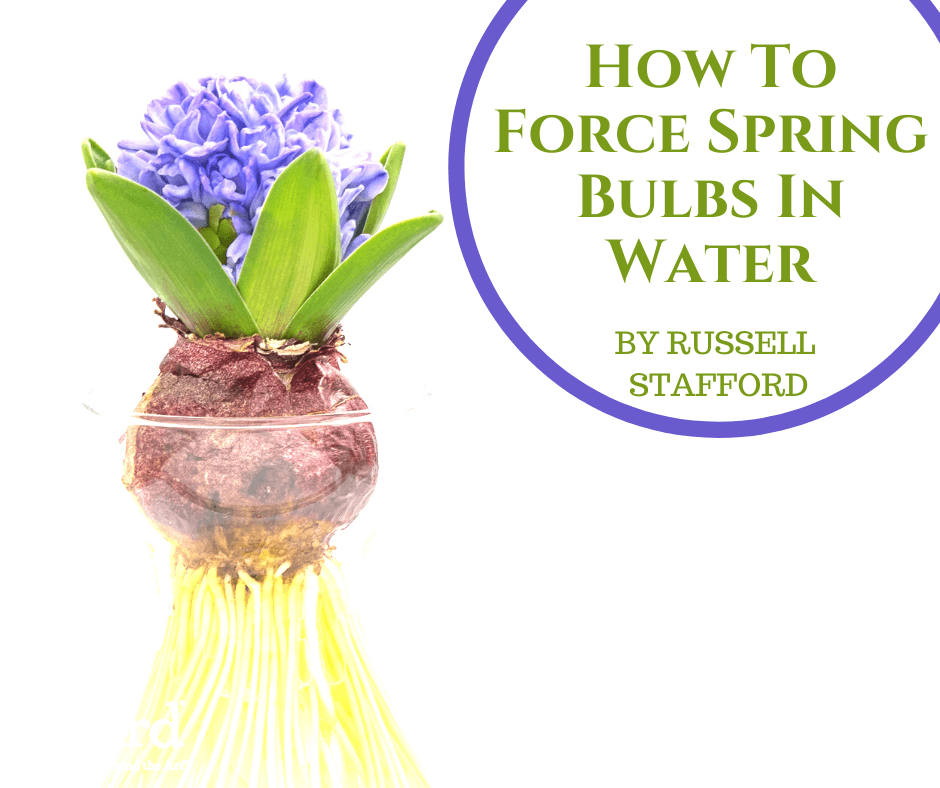

Most other bulbs are generally not as fine with sitting in an inch of water. Fortunately, you can buy forcing jars made just to address this challenge. The bulb nestles in a bowl-shaped receptacle at the top of the jar, which is filled with water just to the bulb’s base. Add water as needed to keep the developing roots immersed.

Amaryllis

Bulb-jars purpose-made for amaryllis (botanically known as Hippeastrum) are available from several suppliers. Some are vase-like bulb supports, while others provide space for pebbles to be placed at the base for root support. As with paperwhites, newly bought amaryllis can be forced directly with no pretreatment necessary. Within weeks, you’ll reap the reward of a spectacular display of huge, richly hued, trumpet-shaped blooms. (Click here to learn more about growing Amaryllis.)

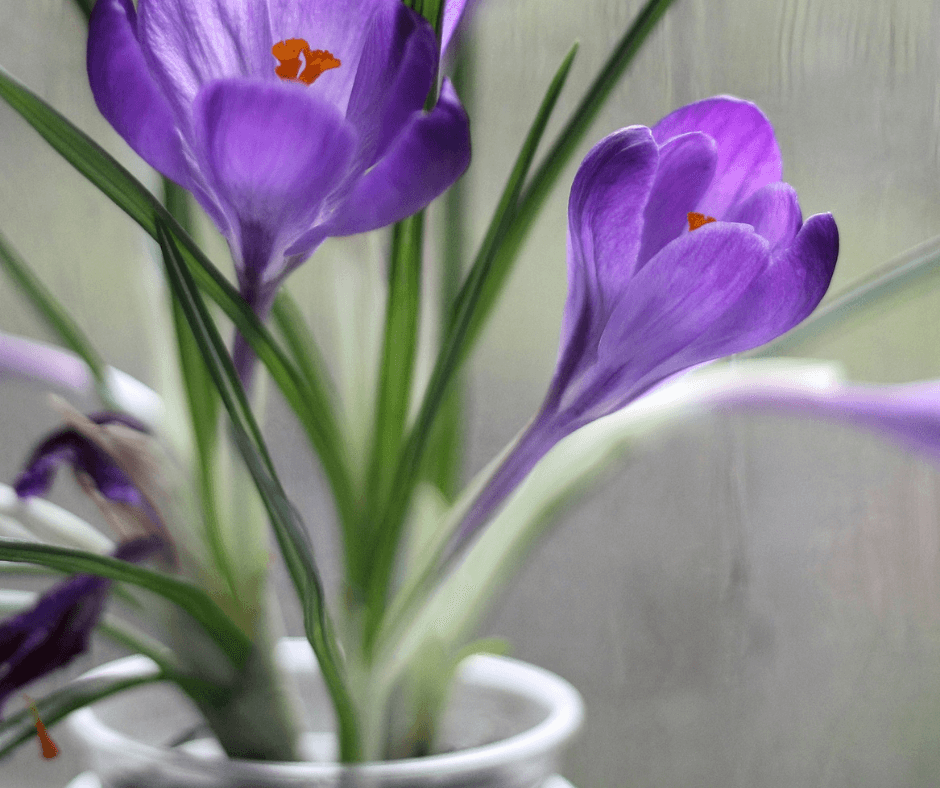

Hyacinths, Crocus, and More

You’ll also find bulb-jars designed specifically for hardy bulbs such as hyacinths, crocuses, or whatever else will fit (scillas, grape hyacinths, trumpet daffodils, and early tulips are among the other bulbs that force well). Hardy bulbs present a special pretreatment challenge, though: many of them won’t send up flowers until they’ve experienced a few weeks of cold and have started rooting. One easy solution is to put the jarred bulb in a refrigerator or other chilly, dark place for several weeks, and move it into the light and warmth once roots extend and plump buds appear. Some hardy bulbs, such as Tazetta narcissus (including ‘Geranium’ and ‘Cragford’) and double hyacinths, need only cold; no rooting required. A few weeks in the refrigerator in a paper bag and they’re ready to head for their jars and get growing.

Or you can make your own “bulb jar”. Place pebbles in a narrow cylindrical vase, leaving a few inches of space at the top. Place the bulb (or bulbs) on the pebbles, and add water to the bulb’s base. Proceed as above. In a couple months, you’ll have spring in winter

All spring-blooming anemones like rich, well-drained soil. Wood and snowdrop varieties prefer partially shady situations, while Grecian and poppy anemones relish more sunshine. If your soil is poor or poorly frost-free end it with a high-quality product like

All spring-blooming anemones like rich, well-drained soil. Wood and snowdrop varieties prefer partially shady situations, while Grecian and poppy anemones relish more sunshine. If your soil is poor or poorly frost-free end it with a high-quality product like