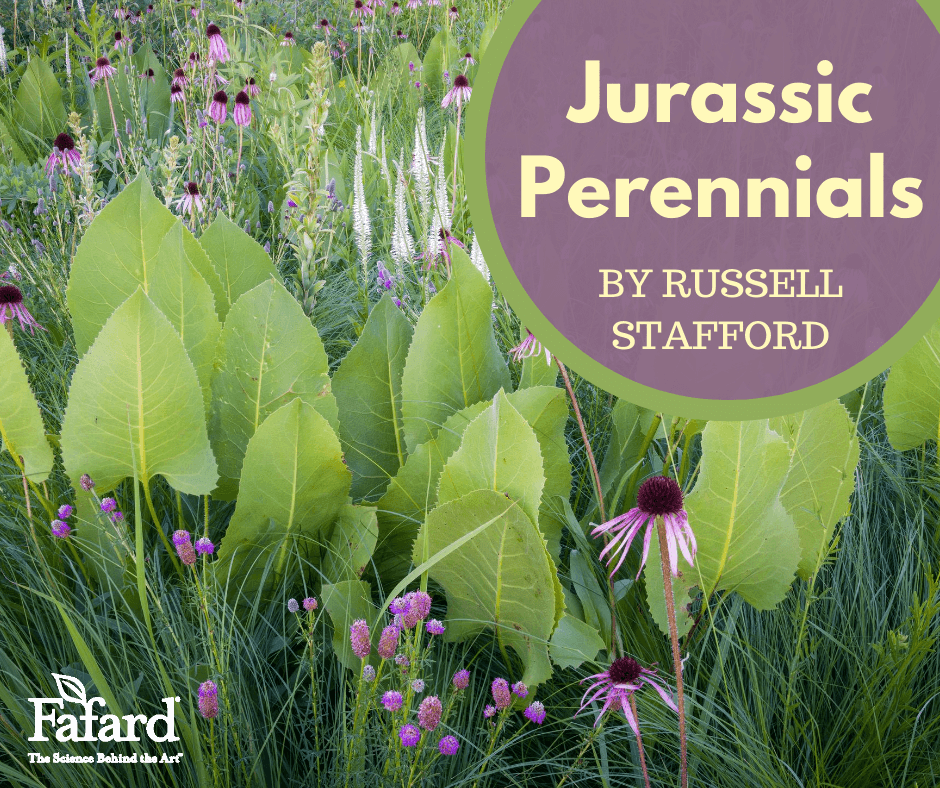

Most garden perennials are bit players, chiming in with their month or two of bloom before fading from the scene. That’s why every perennial border can use a few plants that provide spring-to-fall presence. Among the best such plants are the giant-leaved perennials profiled below. Their lush, bold foliage provides ample interest and structure throughout the growing season, while the flowers of other plants flit by.

Large-Leaved Perennials For Shade

Big, Bold Hosta (Hosta spp.)

Of course! Hostas are shade-garden favorites for several reasons. They’re incredibly tough and adaptable, tolerating drought and other forms of abuse (some will even do well in hot sunny niches). They offer showy and sometimes fragrant flowers (e.g., August lily, Hosta plantaginea) that peak during the summer months. But most of all, they produce broad leaves in a wide variety of colors, shapes, textures, and forms. Behemoths such as ‘Sum and Substance’ and ‘Empress Wu’ mature into 4-foot-tall, 6-foot-broad clumps of huge 2-foot-wide leaves. They’re the sort of thing you can build a whole border around.

Rodgersia (Rodgersia spp.)

Quite a few bold-leaved perennials are native to woodlands, where they use their ample foliage to maximize the capture of sparse sunlight. They’re also often partial to damp soil, to compensate for water lost from their leaves via evaporation. So it is with species of Rodgersia. Emerging late in spring, they unfurl large deeply lobed umbrellas that cover gaps left by flagging early spring perennials. The foliage of some Rodgersia varieties flushes in dramatic shades of burgundy and bronze before fading to green in summer. Flowering occurs in early summer in white or pink sprays reminiscent of their rose-family kin, the astilbes.

Give your rodgersia a moist, fertile, humus-rich soil, and it will wow you with massive clumps of jagged foliage. To get your soil up to snuff, add a generous amount of Fafard Premium Natural & Organic Compost. Astilboides tabularis – a close relative of Rodgersia – produces equally impressive clumps of rounded leaves, and favors similar conditions.

Umbrella Leaf (Darmera peltata)

Also thriving in partial shade and rich moist soil is this Western U.S. native, Darmera peltata, which in favorable sites can grow to 5 feet tall and wide. The 18- to 24-inch-wide leaves arise in late spring on tall stems that attach to the leaf blades at their centers, parasol style. Rounded clusters of pale pink flowers appear on fuzzy stems in early spring, before the leaves break ground. Plants suffer in regions with hot humid summers such as the Southeast United States.

Shredded Umbrella Leaf (Syneilesis aconitifolia)

If you took a Darmera and cut its foliage into lacy segments, you’d have something like shredded umbrella leaf. The 18-inch-wide leaves form shaggy clumps that grow to 2 feet tall and wide. They’re perhaps at their most delightfully shaggy when pushing out of the soil in mid spring. The fat silver-furred shoots look for all the world like miniature trolls emerging to possess the garden.

Japanese Butterbur (Petasites japonicus and hybrids)

Warning: this gargantuan perennial will smother everything in its reach under vigorously spreading clumps of 3-foot-wide leaves. It’s thus best placed in solitary confinement, such as in a driveway island bed. Curious, leafy, rounded clusters of shaggy whitish flowers precede the foliage in early spring, giving no hint of the magnitude of what’s to follow.

Golden Groundsel (Ligularia spp.)

Got a soggy, semi-shaded area in your garden where a mega-leaved plant would look good? Ligularia would be perfect. Ligularia dentata produces expansive, long-stemmed, kidney-shaped leaves that are typically dark green but sometimes verge on black-maroon (as in the cultivar ‘Britt-Marie Crawford’). Large clusters of yellow daisy-flowers open above the 3-foot-tall, 4-foot-wide foliage clumps in midsummer. Other mesmerizing ligularias include L. stenocephala, with clumps of large arrow-shaped leaves topped by tall spires of yellow flowers in summer; and Ligularia japonica, whose rounded leaves are dissected into numerous narrow segments.

Large-Leaved Perennials For Sun

Chinese rhubarb (Rheum palmatum)

Fertile, moist, cool, humus-rich soil in full sun is ideal habitat for this leviathan – particularly where there’s lots of room for its rambling rhizomes. Lobed in maple fashion, the immense leaves measure as much as 3 feet wide. Equally gigantic are the towering plumy white flower clusters on 6- to 8-foot stems in late spring. Variety ‘Atrosanguineum’ features rose-pink flowers and colorful leaves that flush maroon in spring before maturing to the usual rich-green.

Prairie dock (Silphium terebinthaceum)

The upright, oval- to arrow-shaped, 2-foot long leaves of this massive perennial are a signature element of the American prairie. They also make quite the foliar statement in a sunny border. Yellow daisies on statuesque, 6- to 10-foot stems provide a statement of their own in late summer.

Glade mallow (Napaea dioica)

The neighbors may wonder whether you’re growing a particularly robust form of Cannabis sativa. They’ll wonder no longer in early summer when clusters of white flowers open on towering 5- to 7-foot stems. The lush clumps of lobed, foot-wide leaves that are the main reason for growing this midwestern native, however – preferably in moist, fertile, humus-rich soil in full to part sun.

Whether you have sun or shade, plant any one of these grandiose perennials as a bold garden statement. Space is required.