Annuals aren’t just a summer thing. True, many popular annuals – such as marigolds, zinnias, castor beans, portulacas, and celosias – are unabashed heat-lovers, languishing in chilly conditions and hitting full stride during the long sultry days of July and August. Among the most valuable annuals, however, are those that thrive in cool weather. They’re especially useful for filling the floral doldrums that tend to haunt gardens in late spring and fall.

Most cool-season annuals germinate reliably in relatively chilly soil (below 45 degrees F) and tolerate a goodly amount of frost. Sow them outdoors in late winter or early spring (depending on your locale), and they’ll be up and flowering well before the summer annuals get going. Or for extra-early bloom, start plants indoors and transplant them to the garden several weeks before the last frost date. Cool-season annuals take center stage again in the fall. Sow them 3 months before the first frost date for a late floral display, or plant out store-bought plants in late summer.

Great Cold-Hardy Annuals

Some especially cold-hardy annuals – including all of those described below – will even overwinter as seed or seedlings into USDA hardiness zone 6/7 (or colder, in some cases), arising in spring to bloom weeks before spring-sown plants. These can be planted in the garden in the fall as seeds or young transplants, or existing plantings can be allowed to self-sow. If you’re starting plants indoors, be sure to give them lots of light and a good potting mix such as Fafard Ultra Container Mix with Extended Feed.

Pansies (Viola × wittrockiana) are among the most popular cool-season annuals – and for good reason. Not only do they flower continuously in fall and early spring (and beyond), but they also throw some blooms during mild winter spells in USDA zones 6 and warmer. Sold by the thousands in garden centers and other venues in fall and spring, they come in all colors, usually with a signature deep-purple “face” at the flower’s center. Violas – hybrids of Viola cornuta – are close relatives of pansies that also flower prolifically during the cool seasons, as well as in winter warm spells. Short-lived perennials typically bear smaller flowers than those of the pansy tribe, with streaking rather than “faces” at their centers. Both pansies and violas do well with either early-spring or late-summer sowing and planting. The Victorian Posy Pansy mix is an excellent choice for those who start their own flowers from seeds.

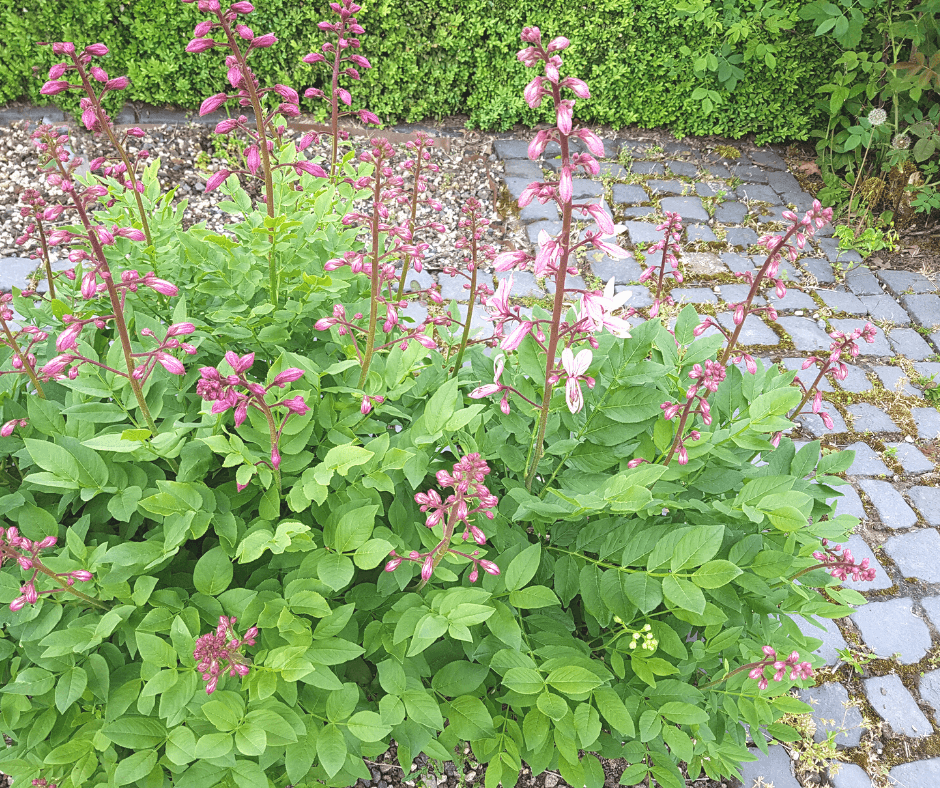

Like pansies, snapdragons (Antirrhinum majus) overwinter outdoors throughout much of the U.S., making them ideal candidates for late-season planting into USDA zone 5. Overwintered seedlings bloom early in the season, lifting their colorful spires to the sun in late spring. In USDA zones 5a and colder, start seed indoors in late winter, a few weeks before the last-frost date. Early-blooming snapdragon varieties such as those in the Potomac, Chantilly, and Costa series provide an additional head-start on the flowering season, blooming days to weeks earlier than other varieties. They flower in the full range of snapdragon colors, including white, yellow, pink, red, and purple.

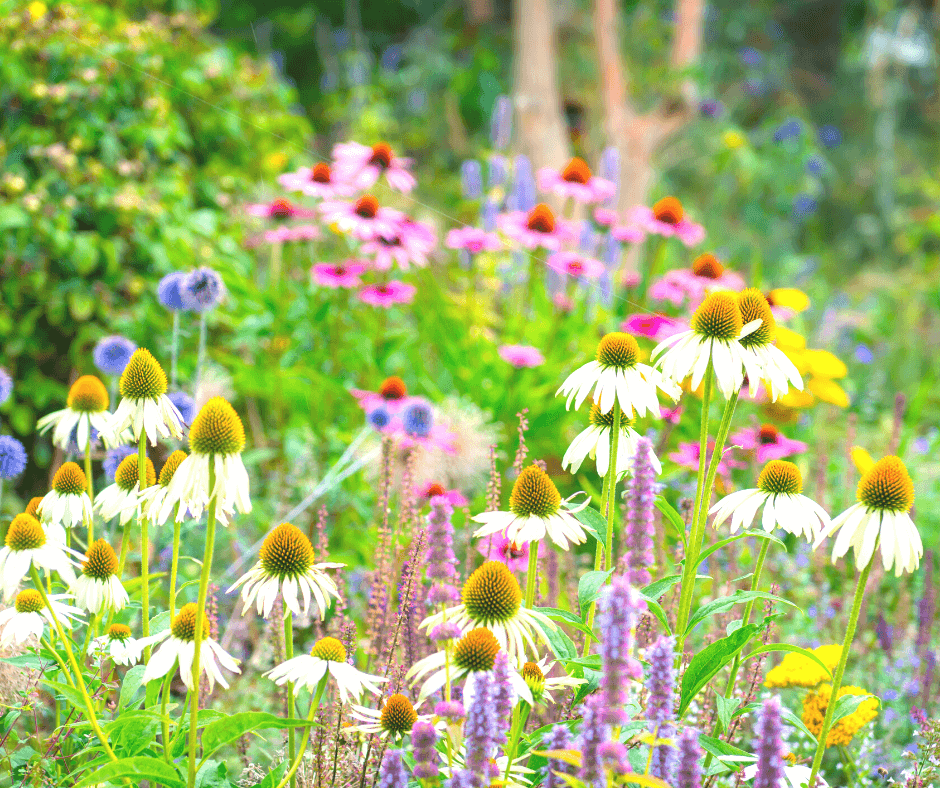

Also ideal for fall planting are gloriosa daisies (Rudbeckia hirta), which are exceptionally winter-hardy (to USDA zone 3). Overwintered plants open their bright yellow to burgundy “black-eyed Susan” flowers in late spring or early summer, repeating until frost. Varieties include ‘Indian Summer’, with classic bright yellow “black-eyed Susan” flowers on 3-foot stems; ‘Cherokee Sunset’, whose double blooms on 30-inch stems come in various tones and combinations of yellow, bronze, and maroon; and the green-coned, tawny-eyed ‘Prairie Sun’. If seedlings don’t survive winter in your area, try sowing seed in the garden in fall, for early germination next spring. Plants will readily self-sow if you don’t deadhead them. Of course, late winter or early spring sowing works too, either indoors or out.

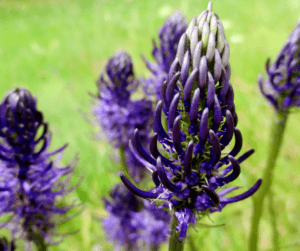

Other classic candidates for fall planting or sowing for spring are Larkspurs (Consolida ajacis) and cornflowers (Centaurea cyanus). They bring an abundance of blue to the late spring garden, in two different forms. Larkspurs produce quantities of dainty butterfly-shaped blooms on 30- to 50-inch spikes. Cornflowers, in contrast, bear frilly pompons atop wiry 3- to 4-foot stalks. In addition to classic blue varieties such as ‘Blue Spire’, larkspurs come in an assortment of other colors including white, pink, lavender, and combinations thereof. Cornflowers, too, are available in a wide color range, from blue (e.g., ‘Blue Diadem’) to pink to red to maroon.

Lesser-Known Cool-Season Annuals

The ranks of cool-season annuals that do well with spring or fall planting or sowing include a number of relatively little-known but highly ornamental species that deserve much wider use:

Blue woodruff (Asperula orientalis) throws airy sprays of little sky-blue flowers on low, typically lax stems. It’s especially lovely in containers, making a lacy understudy for bigger, bolder leaved annuals such as flowering tobaccos and amaranths.

Also flowering in blue is Chinese forget-me-not (Cynoglossum amabile). The clusters of rounded, bright blue blooms do indeed recall those of standard forget-me-not (Myosotis spp.), but they occur on much more durable plants that blossom in late spring and repeat in summer and fall. The pink-flowered variety ‘Mystery Rose’ is equally ornamental.

A perky little thing with spikes of bright blooms that resemble snapdragons, Moroccan toadflax (Linaria maroccana) is perfect for massing in garden beds and containers, in forms such as the pastel assortment ‘Fairy Bouquet’ or bright purple ‘Licilia Violet’.

The poppy tribe contains several cool-season treasures, none better than Shirley poppy (Papaver rhoeas), with its numerous pastel (such as ‘Mother of Pearl’ and the Falling in Love mix) and red (e.g., ‘American Legion’) forms; and Spanish poppy (Papaver rupifragum), a cheerful orange-flowered thing that’s especially winning in its double-flowered form, ‘Flore Pleno’ or ‘Tangerine Gem’.

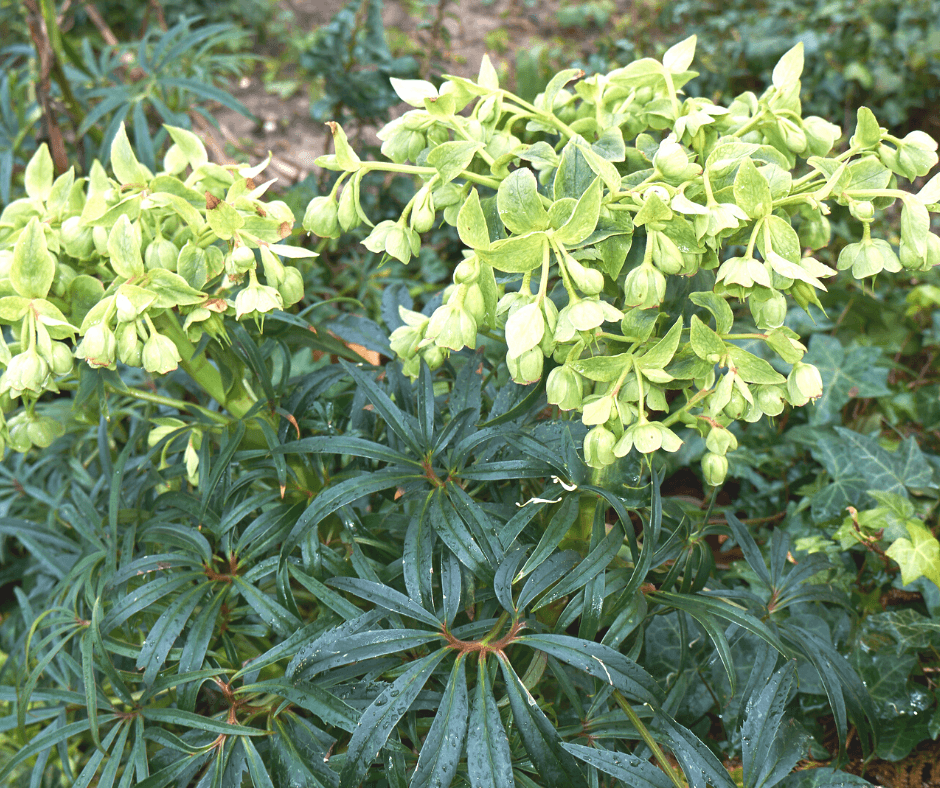

Although not quite as cold-hardy as most of the above, Green-gold (Bupleurum griffithii) weathers winters to USDA Zone 7, and is amenable to late winter and early spring planting in colder zones. Its large flat-headed clusters of chartreuse blooms on 3-foot stems make splendid accents for cut flower arrangements.

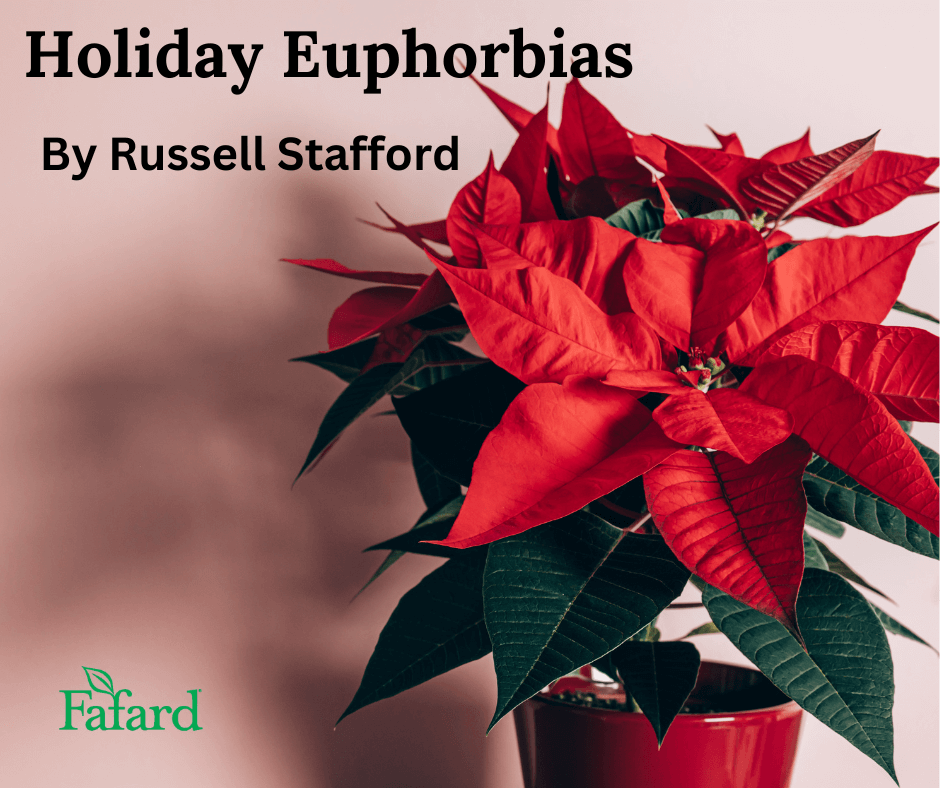

Under whatever name, Euphorbia pulcherrima received little horticulture notice for the first 100 years after its introduction to cultivation in the late 1820s. It was too scraggly and lanky (not to mention cold-tender) for most gardens, and as a cut flower it was too short-lived.

Under whatever name, Euphorbia pulcherrima received little horticulture notice for the first 100 years after its introduction to cultivation in the late 1820s. It was too scraggly and lanky (not to mention cold-tender) for most gardens, and as a cut flower it was too short-lived. It’s easy to keep poinsettias going after they’ve reached your holiday table. Bright indirect light, warmth (55F minimum), and moderate humidity are all to their liking. Water only when the soil surface is dry and the pot is appreciably lighter due to drying.

It’s easy to keep poinsettias going after they’ve reached your holiday table. Bright indirect light, warmth (55F minimum), and moderate humidity are all to their liking. Water only when the soil surface is dry and the pot is appreciably lighter due to drying. A second – and characteristically prickly – holiday icon from the genus Euphorbia is crown of thorns, Euphorbia milii. Inflorescences comprising paired red-orange lip-shaped bracts cluster toward the tips of this spiny, sparsely branching, 2- to 3-foot shrub. Plants that receive ample light flower almost continuously. Spoon-shaped leaves are spaced along the branches, with plants becoming bare toward their base with age.

A second – and characteristically prickly – holiday icon from the genus Euphorbia is crown of thorns, Euphorbia milii. Inflorescences comprising paired red-orange lip-shaped bracts cluster toward the tips of this spiny, sparsely branching, 2- to 3-foot shrub. Plants that receive ample light flower almost continuously. Spoon-shaped leaves are spaced along the branches, with plants becoming bare toward their base with age.