Mums Everywhere

From late August through at least the end of October just about every merchandiser that sells plants features a full range of chrysanthemums in an array of colors. These beautiful fall bloomers are generally cushion mums and are often labeled as “hardy”, but, in fact, they are raised under carefully controlled conditions to provide an impressive seasonal display, not an annual reappearance in the garden. Sometimes, if you plant these mums in protected spots many weeks before the first frost, they may establish roots and survive the winter. If you are an avid gardener and conditions are just right, you might try that, but the vast majority of people treat hardy mums as annuals. After the flowers fade, most of the plants are bound for the curb or compost pile.

I have successfully overwintered a few “hardy” mums, and they have surprised me by flowering in successive years. But for reliable fall color, the best bet is old-fashioned garden mums, now available in some garden centers and through online vendors.

Reliable Bloomers

Among the most reliable garden mums are the plants sometimes called “Korean chrysanthemums”, even though they did not actually hail from Korea. Instead they were most likely descended from a species with the nearly-unpronounceable name of Chrysanthemum zawadskii, which is native to Korea, Japan, northern China and Manchuria. English botanist Graham Rice theorized that the zawadsii chrysanthemums may have been crossed with a Japanese dwarf species, Chrysanthemum yezoense. The result was the so-called “rubellum” group of mums (sometimes known as Chrysanthemum x rubellum), which cropped up in England around 1929 and arrived in the United States in 1936.

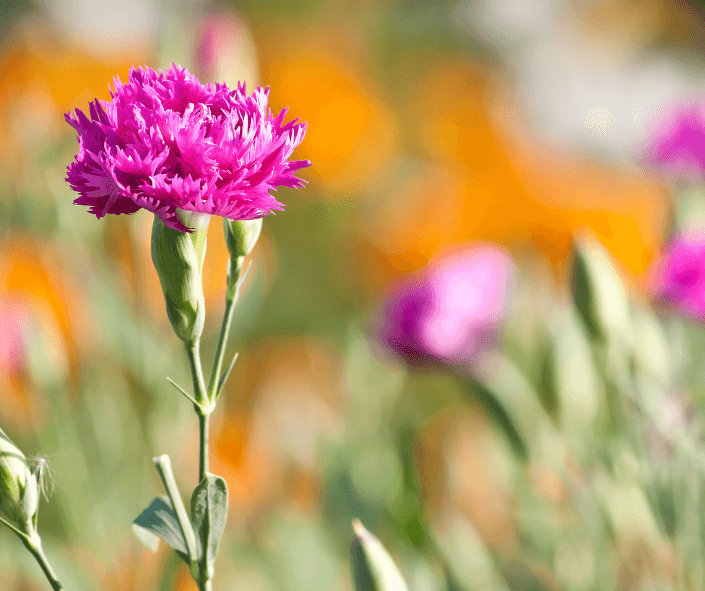

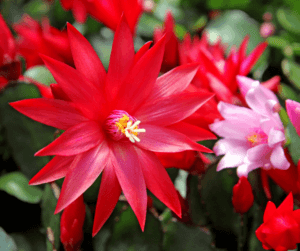

The rubellums caught the eye of Alexander Munnings, a Connecticut breeder and nurseryman. Munnings promptly crossed them with other mum species. The result was the Korean chrysanthemums, which are distinguished by a daisy-like appearance and a growth habit that is looser and less formal than the common garden center varieties. Korean chrysanthemums are generally later bloomers, bringing down the curtain on the fall growing season. Masses of them bloom each fall around Halloween in the Conservatory Garden at New York’s Central Park.

Old Favorites With New Appeal

Now that gardeners have rediscovered the beauties of plants with a “wildflowery” look, the Korean chrysanthemums have come into their own once more. One of the best known is ‘Clara Curtis’, with narrow pink, daisy-like petals surrounding golden centers. At 18 to 24 inches tall and wide, it grows will in either gardens or large containers, and will return reliably year after year, increasing in size in congenial surroundings. ‘Sheffield’ is a little taller, with the same flower form adorned with apricot-colored petals.

‘Mary Stoker’ has been delighting gardeners with its yellow flowers since its introduction in 1942. Depending on light and soil conditions, those blooms may have a slight pink or apricot tinge. Light shade is no deterrent to the plant, which also grows relatively quickly.

Another popular rubellum type is the color-shifting ‘Venus’, with a daisy form and petals that open white and age to pale pink.

Happy Plants, Abundant Flowers

Like other daisy and chrysanthemum types, the rubellum mums prefer a sunny spot and absolutely must have well-drained soil to combat root rot. At planting time, amend heavy soil with a good organic amendment like Fafard® Premium Natural and Organic Compost. Established plants can get through dry spells, but do better with a bit of supplemental water during weeks with no rain. Promote branching and good flower production by cutting back the tips of young shoots around Memorial Day and the Fourth of July. The plants appreciate winter mulch, which should be removed in early spring. Happy garden mums will multiply via underground roots and can be easily divided every few years, and will generally be ignored by deer and other garden marauders.

Finders Keepers

In the fall, you may be able to find Korean orat good local nurseries and garden centers, generally displayed among the perennials, rather than with the cushion mums. This gives potential buyers the advantage of being able to see the plants in bloom. Online vendors also carry selections of these longtime favorites, sometimes in both spring and fall inventories.

About Elisabeth Ginsburg