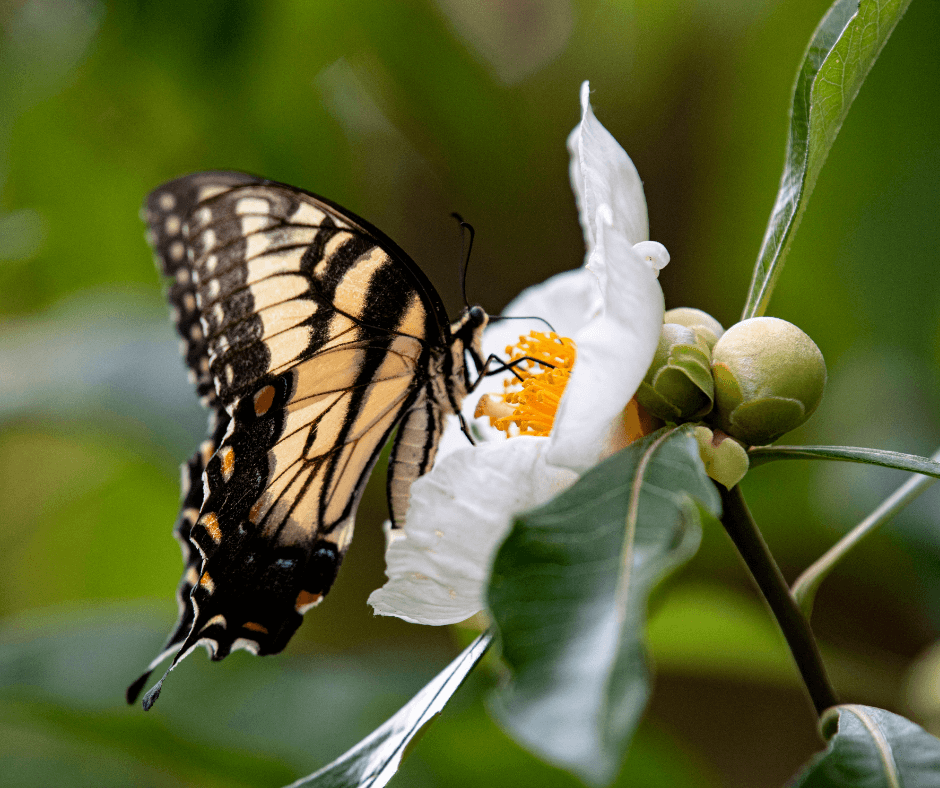

In spring, when everything bursts into flower, the world is full of trees in bloom. But springtime is also the time to plan and plant ahead for the season, anticipating flowering trees and shrubs with a different time of bloom, like Stewartias. Their large, ivory, Camellia-like flowers would be worthy of a spring show, but they arrive in late summer when gardens are in need of their beauty.

The fact is, stewartias are welcome landscape additions at just about any time, and you can find one to fit just about any size garden. They are also plants that are showy in all seasons, whether in flower or not. Their mottled bark and beautiful statuesque habits are always lovely, and in the fall you can anticipate colorful leaves. Here are some of the best of these well-behaved Asian trees and shrubs.

Japanese Stewartia

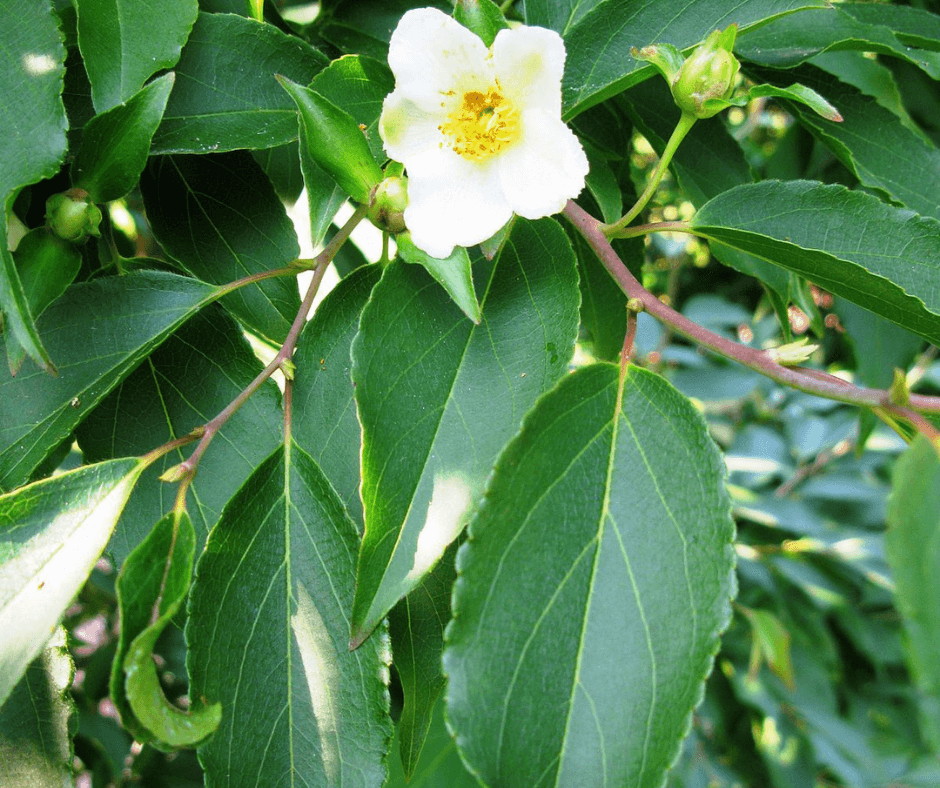

If you have the room, Japanese stewartia (Stewartia japonica) is an all-around great tree that offers four seasons of interest. Growing between 20 and 40 feet tall, with a pyramidal canopy, its branches have slightly toothed, ovoid leaves that are a cooling dark green during the growing season. In the fall, they flame up in shades of yellow, red, and burgundy, putting on a great show.

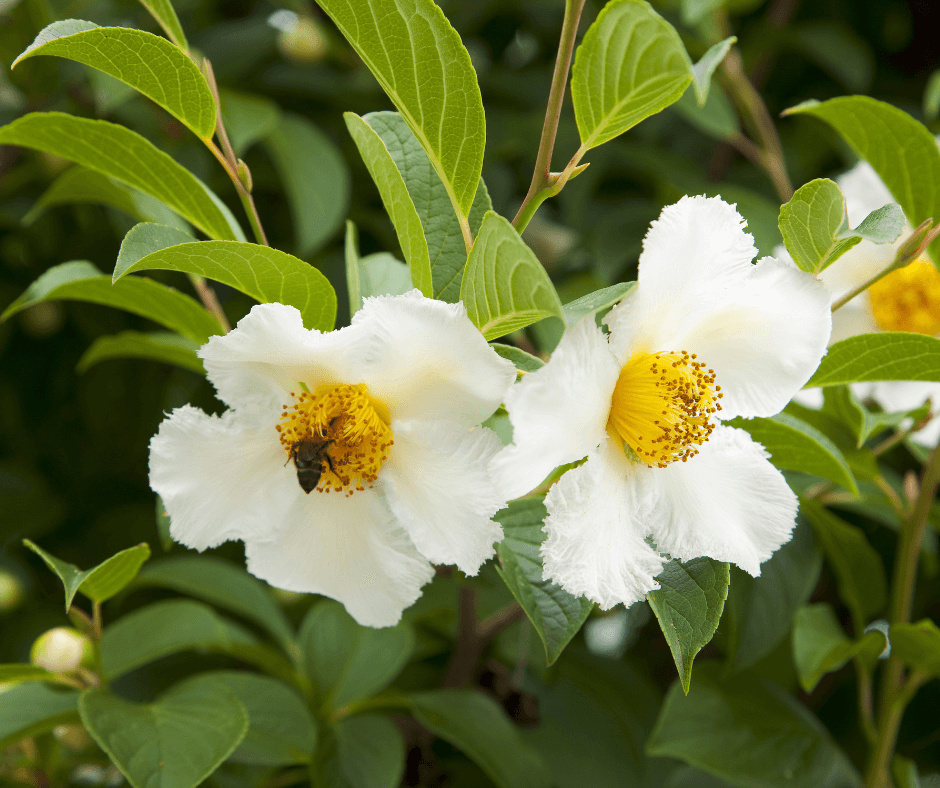

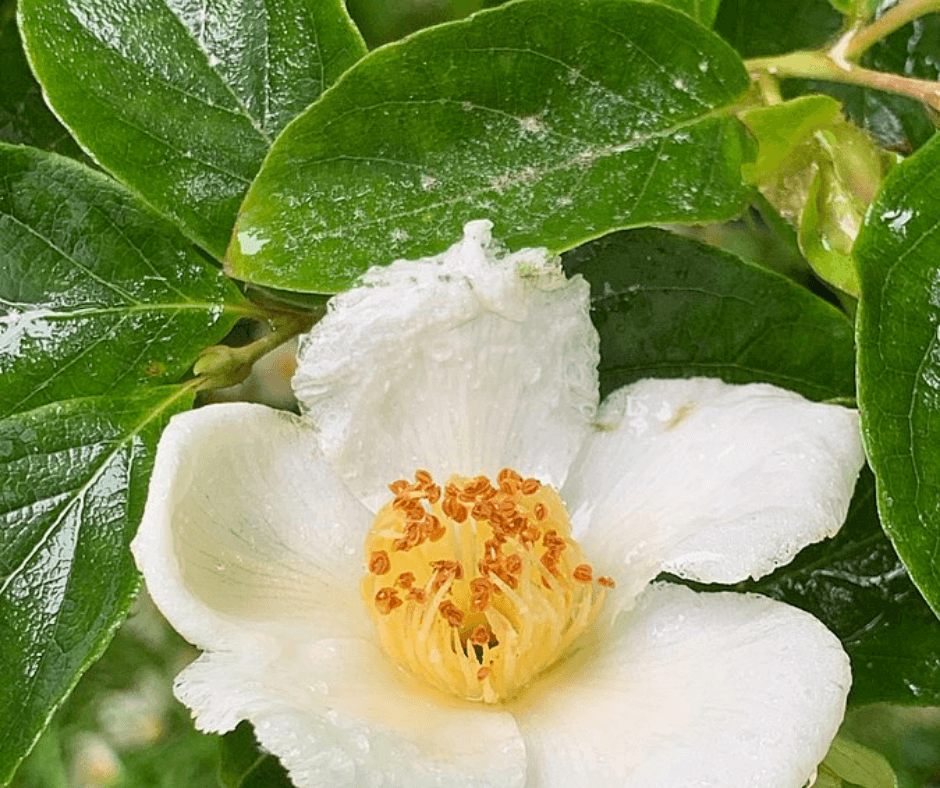

Before all of that foliage drama, Japanese stewartia flaunts its family relationship with camellias by pumping out beautiful, white, Camellia-like flowers. Each bloom is at least 2 inches wide and features five to eight petals surrounding a center of golden-orange stamens. While only minimally fragrant, the flowers are maximally elegant and borne abundantly on trees that are hardy to USDA Plant Hardiness Zones 5-8.

In the colder months, when both leaves and flowers are things of the past, Japanese stewartia continues to shine with multi-colored, exfoliating bark. This bark, which peels gradually from the tree, looks a little like camouflage, but a lot more interesting, with patches of gray, sepia, tawny orange-brown, and taupe covering the trunk. It is a feast for the eyes at all times, but especially in seasons when visual interest may be at a premium.

Tall Stewartia

Tall stewartia (Stewartia monodelpha) is another native of Japan, hardy to USDA Plant Hardiness Zones 6-8, with characteristics similar to those of Japanese stewartia. Young plants have a somewhat shrubby habit, but assume a tree form with age, reaching up to 25 feet tall in height. Tall stewartia features large, dark-green leaves that turn deep red in the fall. The bark does not exfoliate as colorfully as that of Japanese stewartia, but as the tree ages, the bark smoothes out and turns a stunning shade of cinnamon brown. The camellia-like flowers are more cupped in shape than those of other stewartias and sport attractive anthers in their centers.

Chinese Stewartia

Chinese stewartia (Stewartia sinenesis), which is hardy to Zones 5-7, can be grown in tree or shrub form. Left to its own devices, it will reach 15 to 25 feet tall, but like other stewartias, it can be kept smaller when pruned after flowering. The white flowers are somewhat smaller than those of Japanese stewartia but are profuse and surrounded by leaves that are reddish when emerging in spring, dark green in summer, and red again in the fall. The cinnamon-brown bark exfoliates in strips to reveal smooth, tan underbark, sometimes with pinkish overtones.

Mountain Stewartia

The Asian stewartias have American cousins, the best known is Stewartia ovata, sometimes known as mountain stewartia or mountain camellia. Native to the southeastern United States, and hardy to Zones 5-9, it is a little smaller than Japanese stewartia with a height and spread of 10 to 15 feet. It also excels in versatility because it can be grown as a tree or a multi-stemmed shrub. Like its Japanese relative and true to its common name, it features Camellia-like flowers and leaves that glow red and orange in the fall. Its gray-brown bark, while attractively ridged and furrowed, does not exfoliate like that of the Japanese species. Still, for those hankering for stewartias, but confined to smaller spaces, mountain stewartia is an excellent choice.

Stewartia Relatives

Stewartia and camellia are both members of the Theaceae or tea family. Their equally beautiful relatives include the all-American Franklinia tree (Franklinia alatamaha), which was discovered in Colonial America and now extinct in the wild. Specimens of this beautiful small tree can be found at many botanical gardens and arboreta. They are also available at select garden centers.

All the stewartias make excellent stand-alone specimens, but can also anchor partly shaded garden beds, and situations that resemble their native habitats at the edges of wooded areas. They thrive best in rich, consistently moist soil and locations that are protected from harsh winds. To get a young specimen off to a good start, mix the soil in the planting hole with a nutritious soil amendment like Fafard Premium Topsoil, which is ideal for boosting the soil of newly planted trees and shrubs. Water regularly while the plants establish sturdy root systems and mulch generously around, but not touching the plants’ trunks or main stems.