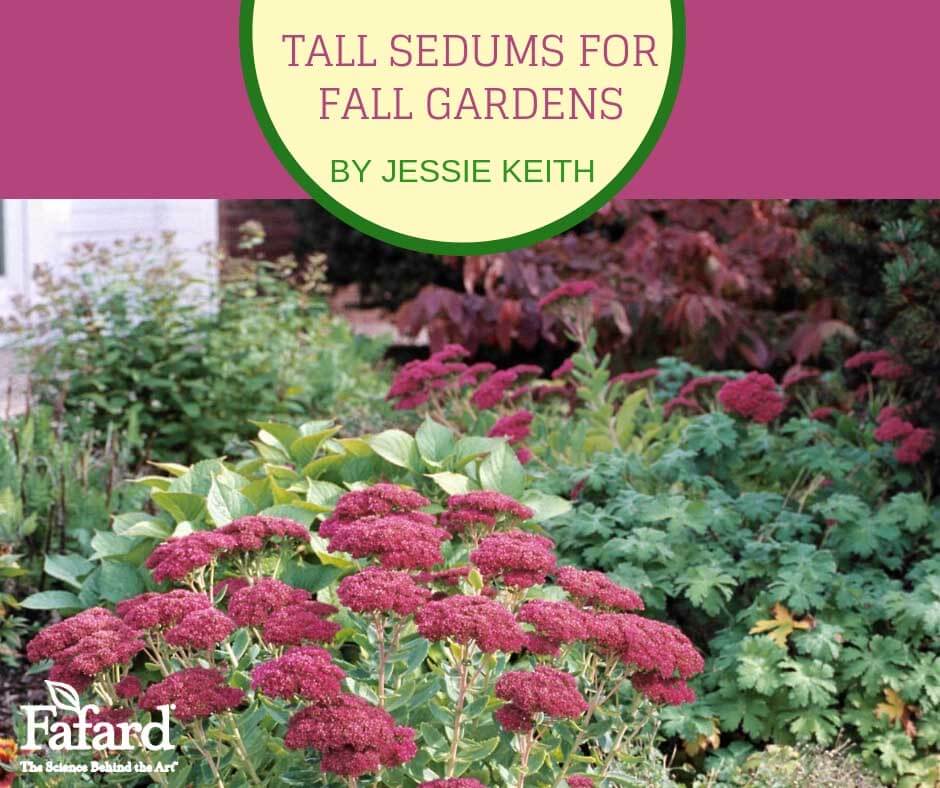

Tall sedums (Sedum spectabile hybrids) provide mounds of lush, blue-green foliage through summer, but late summer and fall are when they really shine. Their sturdy stems support rosy-pink blooms that glow in the late-season sun. New varieties make growing and designing with these tried-and-true perennials even more gratifying and fun.

Bold Tall Sedums & Planting Combos

New tall sedums have broken the mold of the old-fashioned, dusky pink ‘Autumn Joy’ of grandmother’s garden. Extra bright flowers and unique foliage colors, like bronze, purple and near-black, mark some of the newer varieties. Some are extra tall while others are very compact and more densely flowered.

Sedum ‘Thunderhead’

Take the ‘Thunderhead’ introduction by Terra Nova Nurseries, its giant, bright, rose-red flower heads stand on strong, 18-inch stems above bronzy green foliage. For a great combo, plant it in swaths alongside soft, mounding, blue-green ‘Blue Zinger’ sedge and bright yellow-flowered Helianthus ‘Low Down’, which only grows to 2 feet high.

Sedum ‘Dark Magic’

One for outstanding foliage as well as flowers is the 2015 introduction ‘Dark Magic’, which has deepest burgundy foliage all season and large heads of burgundy pink flowers in late summer and fall. The compact plants only reach 12-inches high, making this a great plant for border edges. Its upright habit complements lower, mounded grasses and perennials like evergreen, lavender-flowered germander (Teucrium chamaedrys) or tidy thyme (Thymus spp.) plants.

Sedum ‘Crystal Pink’

For a lighter more silver-pink flower try the compact ‘Crystal Pink’, which becomes completely covered with clouds of palest green and pink flowers in late summer or fall. Plants reach no more than 12-inches, and their light flowers complement taller, darker-colored annuals and perennials.

Sedum ‘Frosty Morn’ and ‘Autumn Delight’

Another cheerful sedum is the cool ‘Frosty Morn’. This variegated counterpart to ‘Autumn Joy’ is surprisingly vigorous. Its bright mounds of foliage complement darker-leaved plants and are best planted in clumps of five to seven plants to show off the effect of the ivory-edged leaves. Late in the season, they become topped with subtle, dusty pink flowers. A bolder variegated sedum is ‘Autumn Delight’, which sports chartreuse and blue-green variegated leaves and bright rose flowers.

Sedum ‘Autumn Fire’

Gardeners looking for classic tall sedum looks but more exciting flowers might consider ‘Autumn Fire’. Their flattened clusters of rose-pink flowers are rich rosy pink, and the plants themselves have a significant presence in the landscape with their dense stems that reach 2 to 3 feet high.

Growing Tall Sedums

Growing Tall Sedums

Tall sedums prefer drier feet, but they aren’t as drought tolerant as some of the short, spreading Sedum species able to withstand really high heat and drought. Plant tall sedums in porous, mineral-rich soil with added organic matter, such as Fafard Premium Natural & Organic Compost, for perfect rooting.

All sedums attract bees and butterflies, making them perfect for pollinator gardens. After fall flowering, the seedheads should be left until they are no longer ornamental. In early winter, they hold up moderately well before being flattened by snow. Cut them back on a dry midwinter’s day, and wait until the soils warm in spring and their rosettes of fleshy leaves begin to grow again.