Edible landscaping can be a kick – especially if you take full advantage of the dizzying diversity of fruiting trees and shrubs. While old-time (and often pest-prone) favorites, such as apples and pears, certainly have their place, so too do scores of lesser-known but equally rewarding fruit-bearing species, including those portrayed below. They’ll bring excitement and new flavors to your garden – as well as fewer pest problems than those ubiquitous old-timers. And many of them are beautiful to boot (which can’t be said of most apple and pear trees).

Carpeting Cranberries

Home-grown cranberries (Vaccinium macrocarpon, USDA Hardiness Zones 2-7) are so much more rewarding and ecologically friendly than market-bought ones. Even better, the plants that bear them are highly ornamental, their creeping stems weaving into dense ground-covering swaths of dainty glistening evergreen foliage. Give this North American native a moist humus-rich acidic soil and ample sun, and it will steadily spread into a 3-foot-wide, 6- to 8-inch-high hummock that covers itself in ornamental red berries in late summer.

Commercial cranberry varieties such as ‘Stevens’ produce especially heavy crops. Where space is limited, consider the dwarf cultivar ‘Hamilton’, which tops out at a foot wide and 4 inches high, but with normal-size berries. Plant two or more different varieties for maximum berry production. Native mostly to latitudes north of the Mason-Dixon Line, cranberry does best in areas with chilly winters and relatively unoppressive summers. Dig a couple of inches of Fafard Ultra Outdoor Planting Mix into the soil before planting, and your cranberries will be extra-happy.

Also effective (and productive) as a small-scale ground cover is cranberry’s close cousin, lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea, zones 3-7). Similar to cranberry in habit, foliage, preferred garden habitat, and culinary uses, it bears clusters of pale-pink, urn-shaped flowers in late spring and summer that ripen to tomato-red pea-sized fruits in late summer and fall. Lingonberries going by the name of Koralle yield abundant fruits on spreading 8- to 12-inch-tall plants. The vigorous, large-fruited cultivar ‘Red Pearl’ grows a few inches taller and wider than Koralle.

Harvestable Hedges

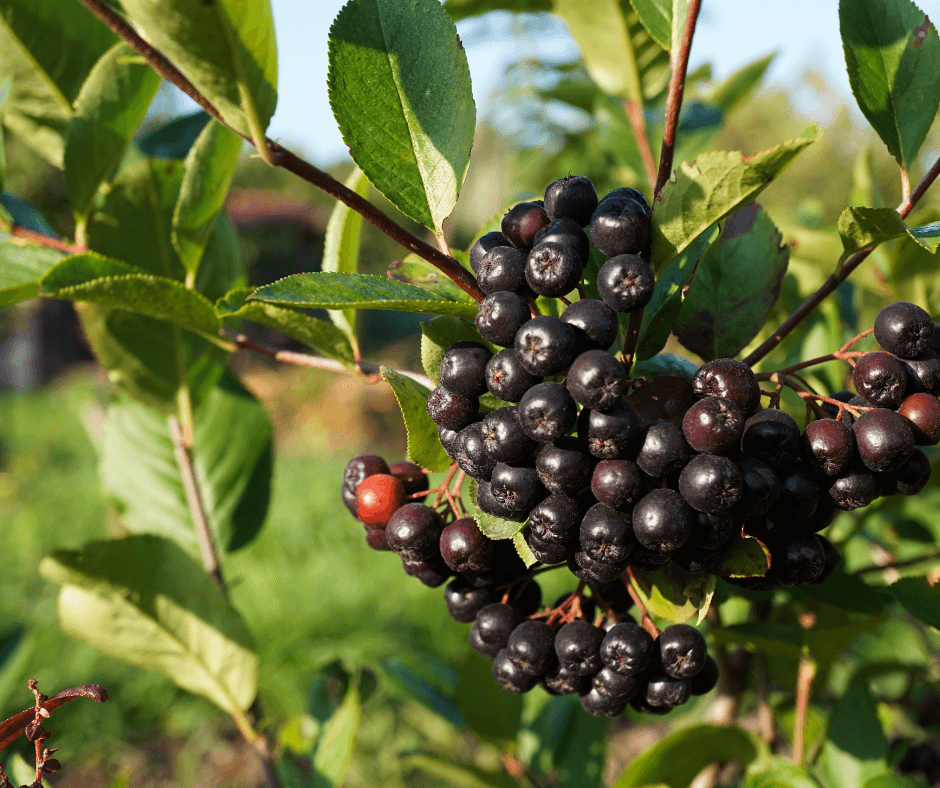

A significant food crop in Europe, the eastern North American native Aronia melanocarpa (commonly known as black chokeberry) is surprisingly absent from American orchards and gardens. Yet this rugged deciduous shrub makes an outstanding ornamental and culinary plant for sunny niches throughout USDA Zones 3 to 8. Plants typically form suckering 3- to 5-foot-tall clumps clad with glossy-green oval leaves that turn brilliant sunset shades in fall. Abundant clusters of white flowers open toward the branch tips in mid-spring, followed by tart-flavored, quarter-inch-wide berries that ripen black-purple in late summer. The fruits are excellent for preserves, pies, and other kitchen uses. With its dense habit, black chokeberry works wonderfully as a low garden or boundary hedge.

Commercial cultivars such as ‘Viking’ (which may be a hybrid with mountain ash, Sorbus aucuparia) produce the largest berries, on vigorously suckering stems. For residential gardens, ‘Autumn Magic’ and Iroquois Beauty™ are of relatively compact growth with somewhat smaller – but still toothsome – berries. Two newly introduced cultivars (Ground Hug™ and Low Scape Mound®) from the University of Connecticut’s breeding program are even more compact, maturing at 1 to 2 feet tall and producing modest crops of fruit. For maximum production, plant more than one cultivar of black chokeberry.

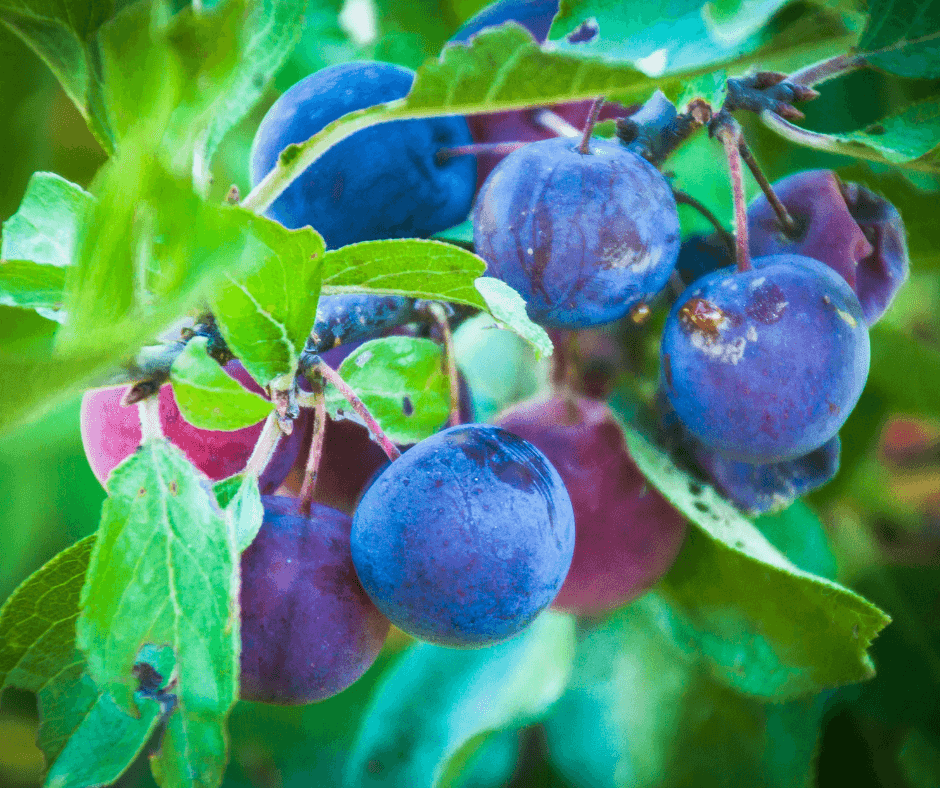

The tart, grape-sized fruits of beach plum (Prunus maritima) may be small, but they’re unsurpassed for flavoring preserves, syrups, vinegar, and the like. Thousands of beach plum aficionados descend on Eastern Seaboard dunes in August and September to harvest the red-purple ripe fruits. Curiously, however, very few gardeners in beach plum’s Zone 3 to 8 hardiness range recognize its considerable merits as a culinary and ornamental plant.

Although a rather scraggly 3- to 5-foot thing in its native dune habitats, in average garden soil it forms a dense 6- to 12-foot clump well-suited for hedging. Blizzards of white flowers in mid-spring are followed by fruits if another beach plum is nearby for cross-pollination. Most plants bear irregularly from year to year, so look for selections – such as ‘Premier’ and ‘Jersey Beach Plum’ – that are more consistent producers. Cultivars ‘Nana’ and ‘Ecos’ bear reliable annual crops on more compact 3- to 5-foot-tall plants. You can further enhance beach plum’s productivity and habit by thinning out old, unproductive branches in early spring (this also works for the other shrubs described here).

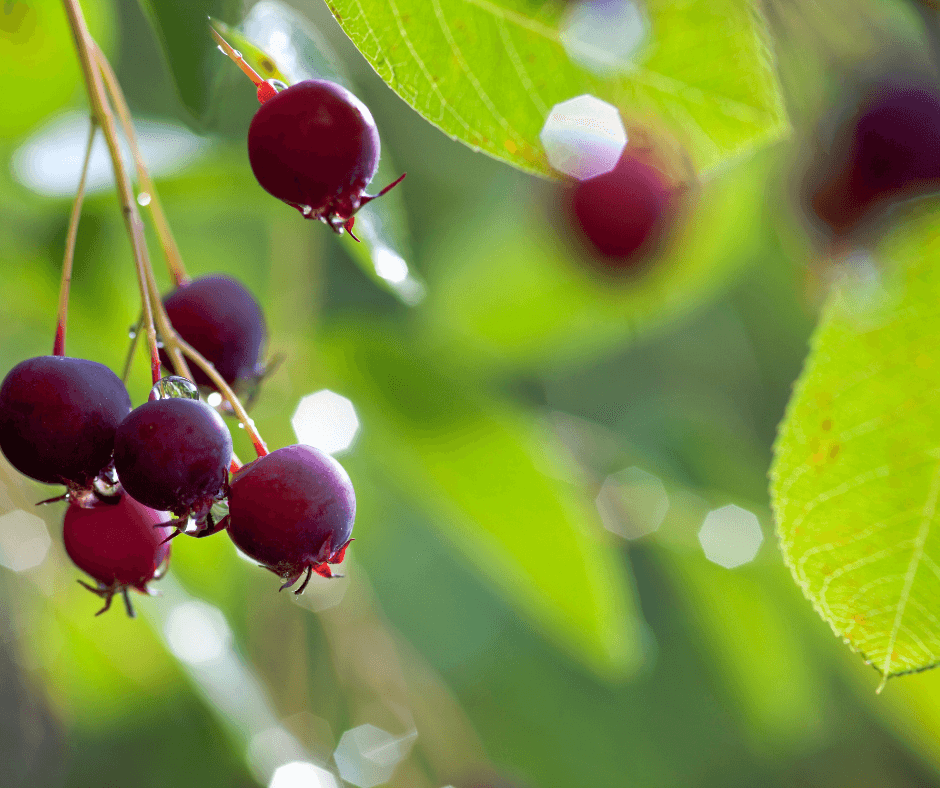

From upper latitudes of western North America comes another first-rate hedging and fruiting shrub, Amelanchier alnifolia ‘Regent’. A compact selection of one of several small native tree species variously known as serviceberry and shadblow, ‘Regent’ tops out at a bushy 6 feet tall, placing its blueberry-like, early-summer fruits in easy reach. Clusters of gossamer white flowers precede the fruits in the earliest spring. Commonly known as saskatoon, this extremely cold-hardy shrub thrives in full sun to light shade and most types of soil from Zones 2 to 7. Plant another variety of Amelanchier nearby to maximize fruiting.

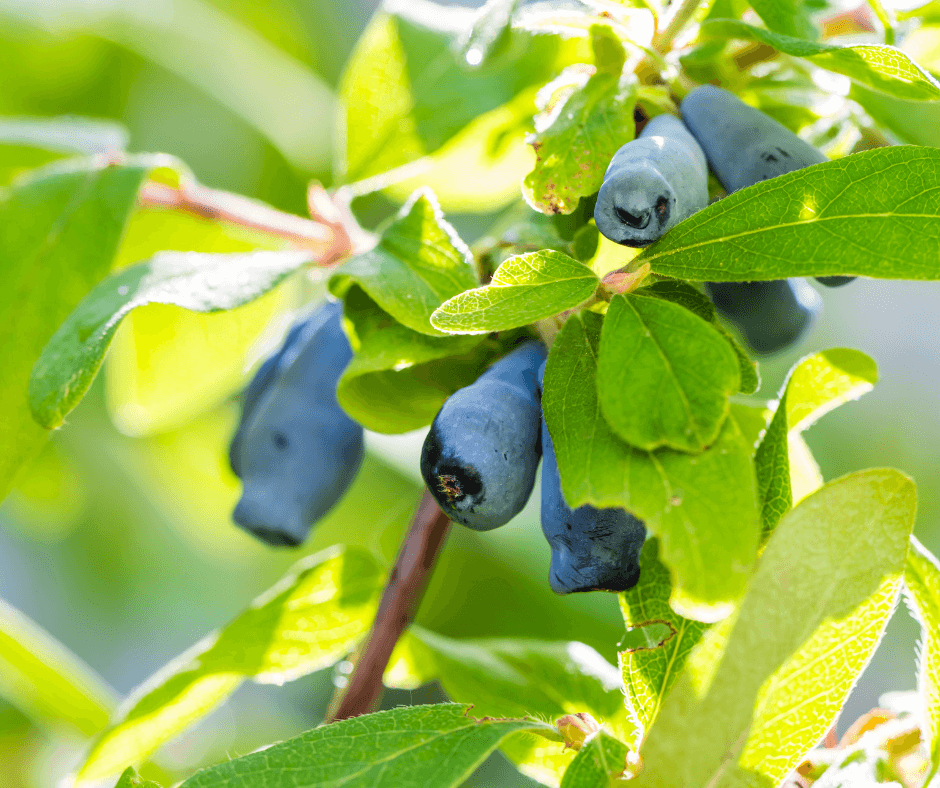

Also producing blue fruit in early summer is honeyberry, Lonicera caerulea. Olive-shaped rather than rounded, the fleshy, tasty berries have similar uses to those of blueberry and saskatoon. They’re borne on attractive 3- to 4-foot plants clothed with dainty, downy, oval leaves that flush just before the pale yellow flowers open in early spring. You’ll need more than one variety for plants to produce fruit, so why not make a hedge of them? Several cultivars of this extremely hardy (Zones 2 to 7) Northeast Asian native are available, including Blue Moon™, Blue Velvet Palm, and Yezberry Sugar Pie®. All prefer full sun but will tolerate some shade.

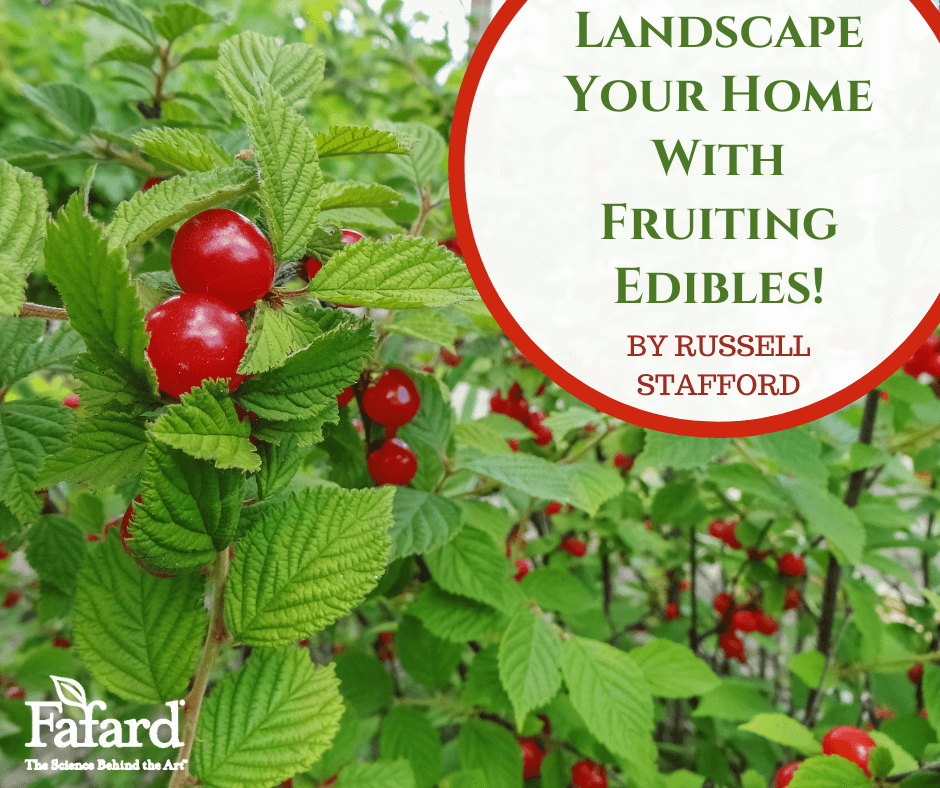

East Asia is also the home of Nanking cherry (Prunus tomentosa), another little-known and highly ornamental fruiting shrub. Its upright to arching stems carry pale pink flowers along nearly their entire length in early spring, before the toothed oval leaves expand. Red, tart to sweet, cranberry-sized “cherries” follow in late spring and early summer, ready for fresh-eating or for making into pies or preserves. Maturing at around 8 feet high and slightly wider, Nanking cherry nicely fills the bill as a large hedging plant for sunny sites in Zones 2 to 7. When available (which is all too rarely), it’s usually offered as unnamed seedlings. Multiple plants are needed for a good fruit-set.

Trend-Setting Fruit Trees

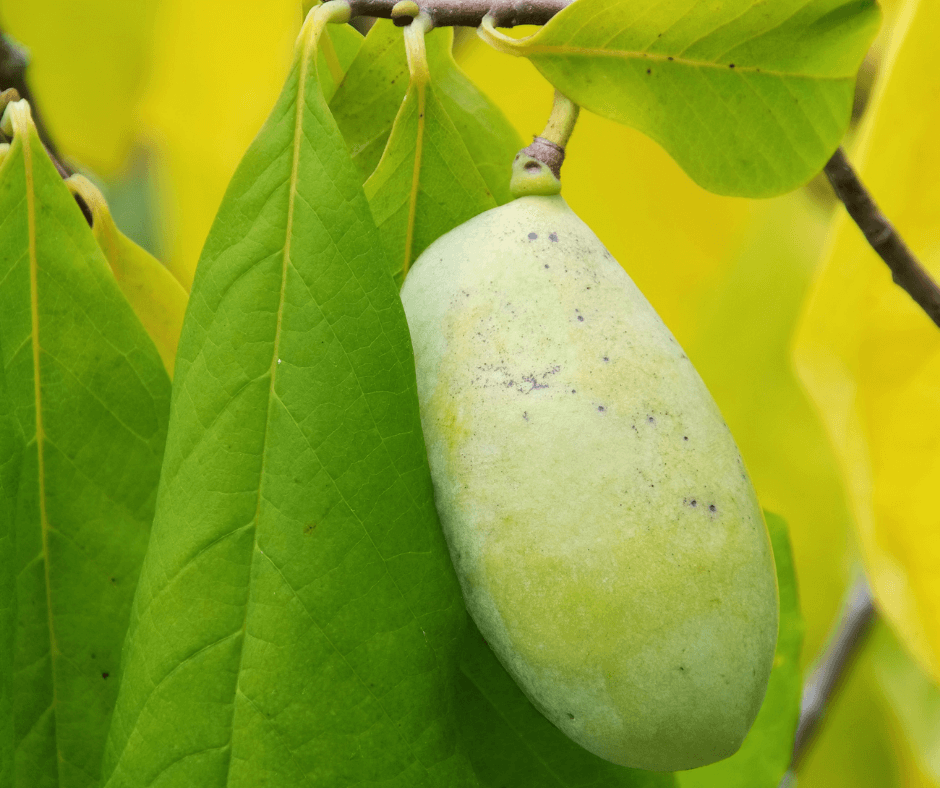

The standard suburban fruit tree is a rather homely, disease-riddled affair. A well-grown specimen of pawpaw (Asimina triloba) is anything but. In its native woodland haunts in the central and southeastern U.S., it grows as a gaunt, unprepossessing understory tree. It’s another thing entirely in a sunny or lightly shaded garden niche, where it typically forms a dense low-branched 15- to a 20-foot tree whose conical crown is densely furnished with large tropical-looking leaves. Curious fleshy liver-purple flowers in early spring give rise to large, potato-shaped fruits that ripen in late summer (two or more varieties are needed for fruiting to occur).

The flavor of the fruits’ custardy flesh varies from tree to tree, as does the number of seeds it contains, so look for varieties that have been selected for their fruiting characteristics. Young pawpaw trees suffer in harsh wind and blistering heat and should be sited or protected accordingly. The Zone 5 to 9 hardiness of this central and Southeast U.S. native belies its tropical appearance.

Also bearing large tasty fruit on handsome small trees is Chinese quince, Pseudocydonia sinensis. Fragrant bright yellow quinces dangle from its rounded crown in late summer, not long before the leaves turn burgundy and orange. This East Asian native is also well worth growing for its pink sweet-scented mid-spring flowers and for its handsome bark that flakes into multi-colored patches. Plants are self-fruitful, so you only need one tree to get the tart fruits, which are delicious in preserves and baked goods. Chinese quince does well in Zones 5 to 9 in full sun and fertile loamy soil.

If your taste buds have ever thrilled with the zingy flavor of Szechuan peppercorns, you should also be thrilled to know that the species that bears that Chinese-peppercorn fruit (Zanthoxylum simulans) makes a striking small tree for the culinary garden. Its spiny trunk and branches grow rather rapidly into an open 15- to 25-foot specimen that becomes characterfully gnarled with age. Pinnate leaves similar to those of mountain ash unfurl in early spring, a few weeks before the inconspicuous clusters of greenish flowers appear. Spicily aromatic, reddish-brown, pepper-like fruit capsules mature in late summer on female plants, which are usually somewhat self-fruitful. Plants offered for sale tend to be self-pollinated seedlings of such female plants, which do not need a male companion to produce peppercorns. Zanthoxylum simulans thrives in sun and well-drained soil from Zones 6 to 9. It functions as a large shrub in Zone 5, where it sometimes dies back in winter.

If you’re looking to literally add distinctive character to your edible landscape this spring, any of the above would be the perfect place to start. There’s always plenty of room to explore in the garden!