You might call osmanthus a great imposter, because shrubs and trees in the genus go by so many names. At various times and places, osmanthus species have been tagged with common names like “false holly”, “tea olive”, “wild olive’ and even the scary-sounding “devilwood”.

It takes some doing to get a handle on this group of ornamental evergreens.

Osmanthus species have nothing to do with Camellia sinensis, the species that provides black tea. Nor are they part of the genus Ilex, home to hollies. They really do not have any associations with the devil, though craftsmen find the hardwood devilish to work with.

The Latin name Osmanthus, is derived from the Greek words for fragrant and flower, so these common names probably fit it best. Some of the common names reference olive, which provides another clue to their true nature. Osmanthus is a card-carrying member of the olive family, Oleaceae, and its members are famous for the fragrance of their clusters of small, four-petaled flowers.

Experts reckon that there are about 15 species of holly olives, which are native to Asia and southern North America. Some flower in spring, while others wait until fall, but all can thrive in home landscapes. Smaller species may also be grown in large containers and overwinter inside in cold weather climates.

Autumn-Flowering Osmanthus

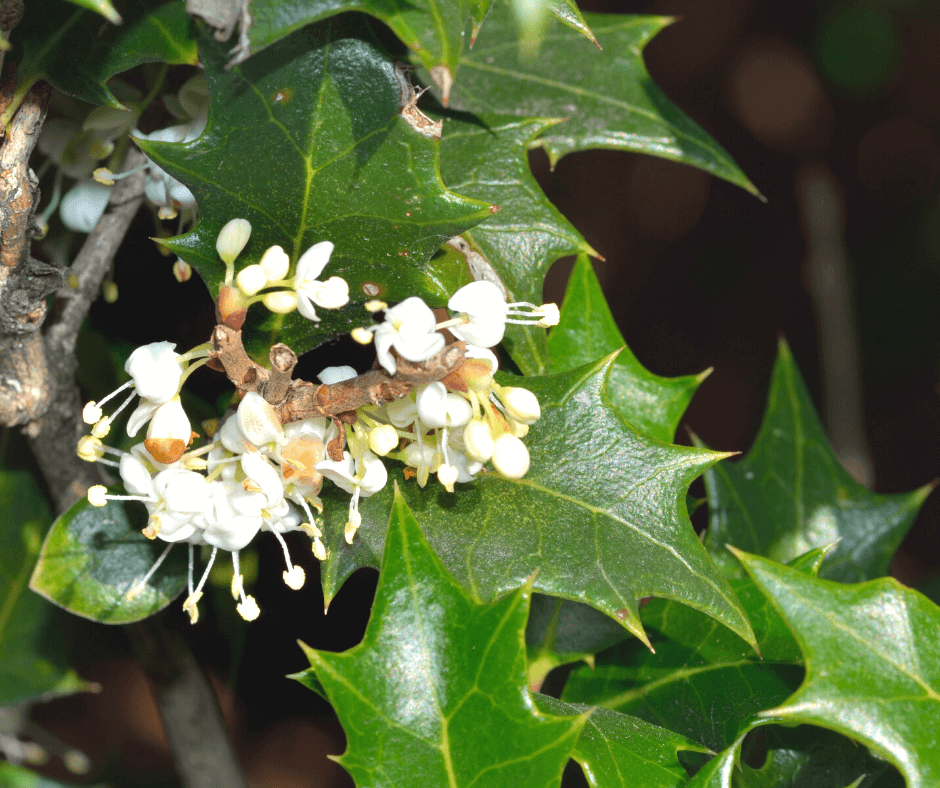

In autumn, as the garden season starts to wind down, holly olive (Osmanthus heterophyllus, Zones 7-9) defies the seasonal trend and pumps out scores of small, white, four-petaled flowers. Many of those flowers hide demurely under the foliage but make their presence known with a pervasive sweet scent. Growing 8 to 10 feet tall and 7 to 9 feet wide, the species can be grown as a large, bushy shrub or standardized into tree form. The leaves are dark green and spiny, like true holly, but close comparison reveals that holly olive leaves are opposite on the stems, while true holly leaves alternate. Though the leafy branches can be used effectively in winter holiday arrangements and decorations, holly olive does not produce the bright red berries that characterize many true hollies.

Many commercially available holly olive varieties bear green leaves, while others, like “Goshiki’ and ‘Kembu’ sport variegated leaves that are blotched or edged in cream. Add light to the landscape with ‘Ogon’, which features bright, golden-green leaves.

For something a little smaller and potentially more manageable in limited space, try sweet olive (Osmanthus decorus, Zones 6-9). Native to areas around the Black Sea in Asia Minor, decorus grows only 6 to 8 feet tall, with tiny, white spring blossoms that perfume the air around the shrub. The oblong foliage is spineless, glossy, and dark green. In fall, the shrubs produce small, purple-black fruits, a testament to the familial link between osmanthus and the rest of the olive family.

Good Fortune: Cross holly olive with fragrant olive and you get Fortune’s olive (Osmanthus x fortunei, Zones 7-10), which can grow 15 to 20 feet tall, with a rounded crown, but is easily pruned to fit smaller available spaces. The hybrid has spiny, holly-like leaves and fragrant fall blooms. One popular variety, ‘Fruitlandii’, is slightly more compact than its parent, with flowers that are creamy yellow instead of white. ‘Variegatus’ offers green and white foliage, plus scented blooms. Fortune’s olive offers better cold hardiness than some other osmanthus species.

Devilwood is a terrible name for (Osmanthus armatus, Zones 7-9), a lovely shrub native to China. Admittedly, the lustrous, holly-like leaves can be spiny on young plant but smooth out on mature specimens. The characteristic white flowers appear in clusters, the better to spread their glorious scent in autumn. Female plants may also produce oval-shaped, dark purple fruits after the flowers drop. Devilwood is most often grown as a multi-branched shrub and can reach eight to 15 feet in height. It is cold-hardy to at least Zone 7 and will tolerate more shade than many other osmanthus species.

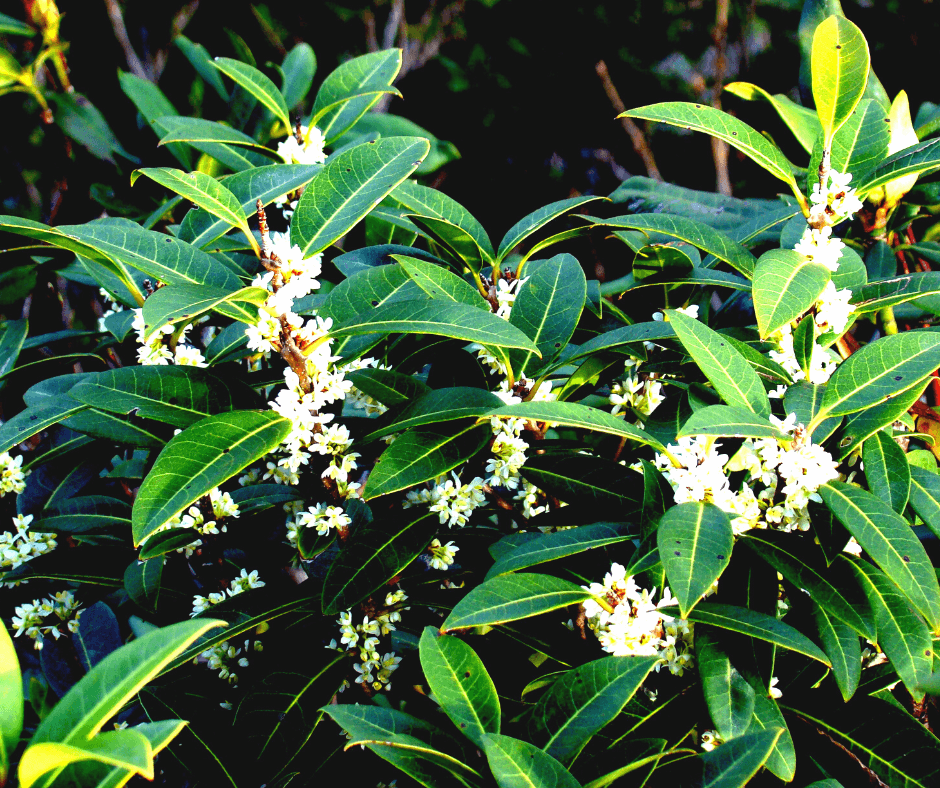

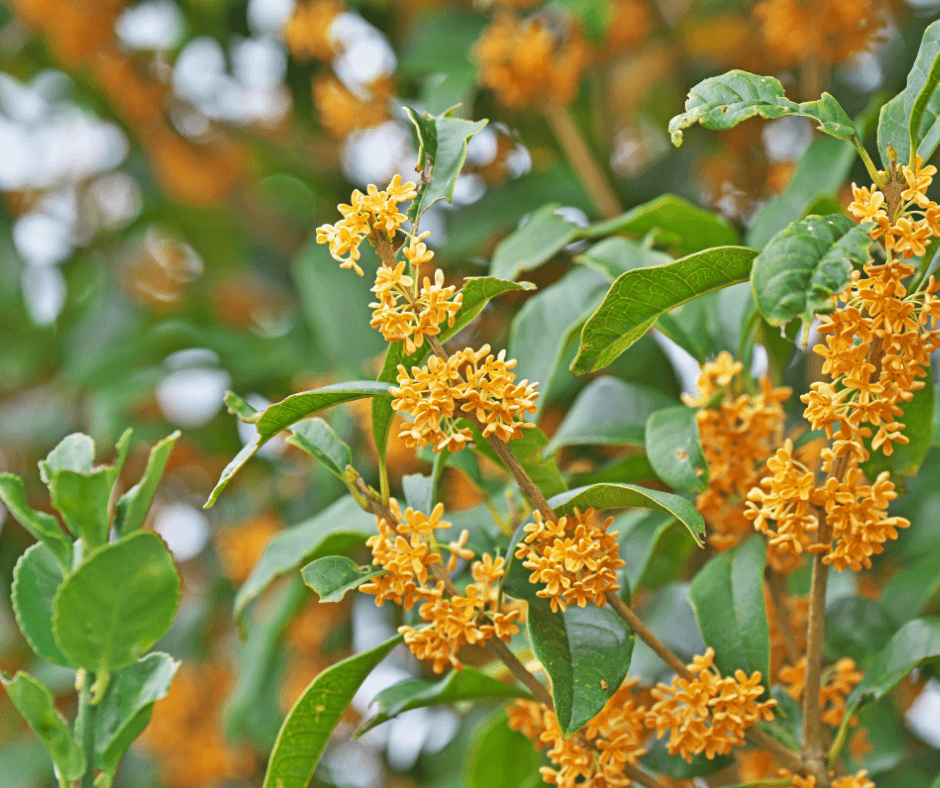

In warm winter climates fragrant olive (Osmanthus fragrans, Zones 9-11), native to Japan and China, contributes strongly scented flowers to the spring garden, along with leathery oblong green leaves. Maxing out at 10 to 15 feet tall and wide, it can be grown as a tree or shrub and pruned to keep the size under control. Unlike holly olive, fragrant olive produces its white blooms in spring. Like most other osmanthus, this spring charmer is relatively unfussy, tolerating clay soil and, once established, drought. The spectacular orange-flowered variety Osmanthus fragrans f. aurantiacus ‘Orange Supreme’ is one to seek out!

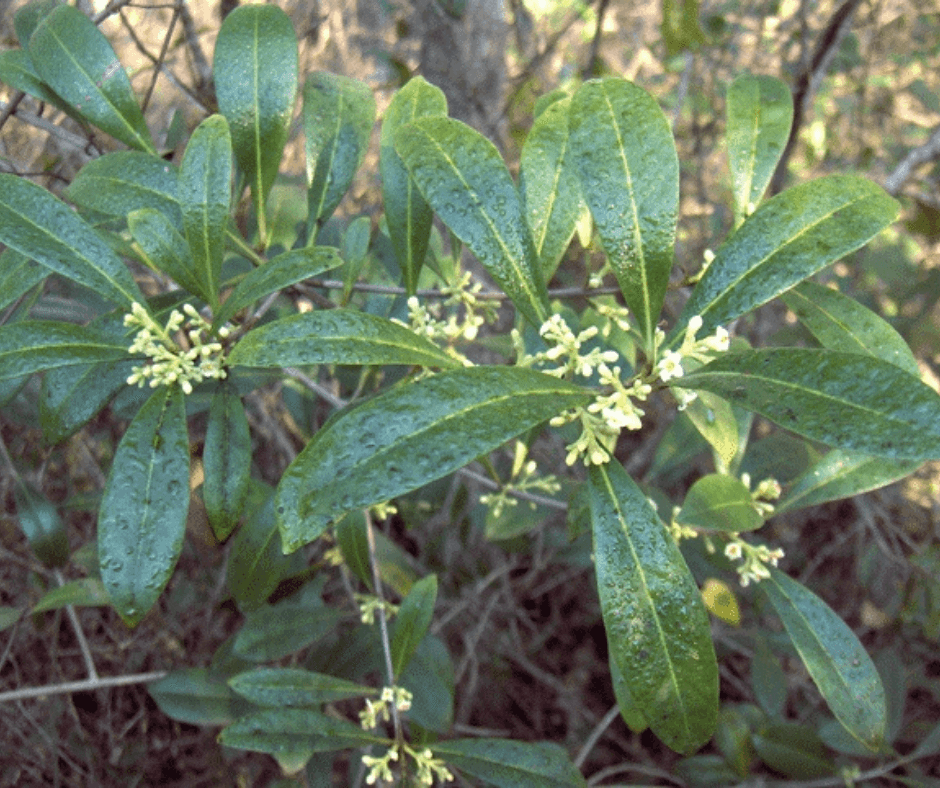

Osmanthus americanus (syn. Cartema americana, Zones 6-10), also known as American or wild olive is also sometimes referred to as devilwood. The elongated leaves, which feature smooth rather than spiny edges are dark green and adorn shrubs that can top out at between 15 and 24 feet high. As with other osmanthus, the fragrant flowers are white, blooming in mid-spring, followed by blue-purple fall fruits. Wild olive is quite cold-hardy.

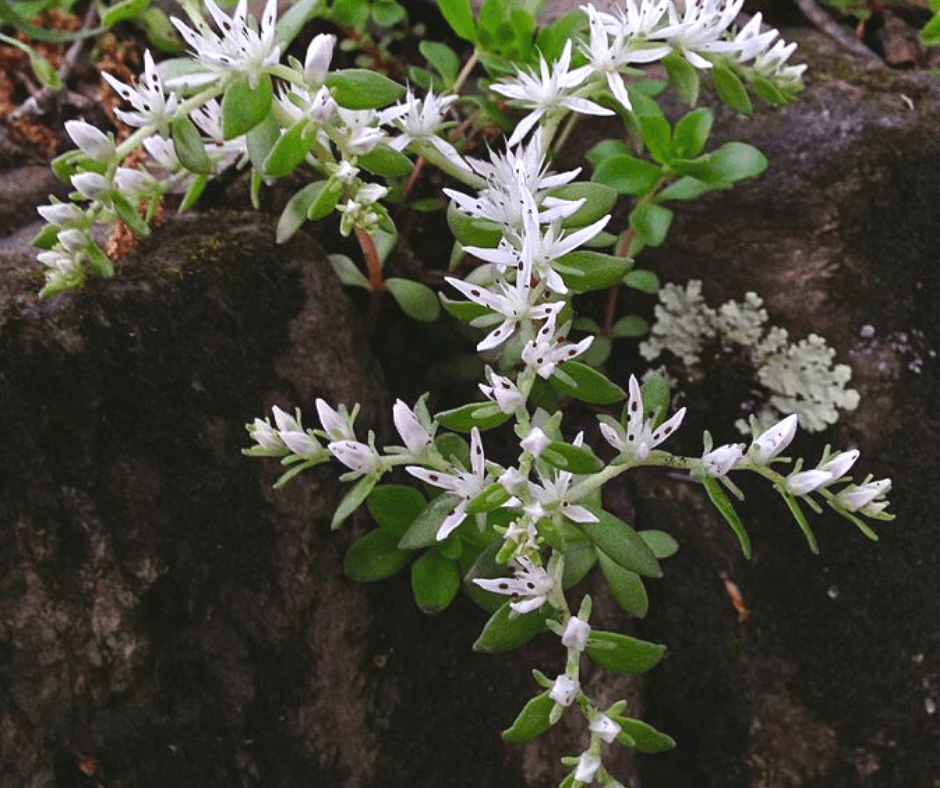

Burkwood’s osmanthus (Osmanthus x burkwoodii, Zone 6) is relatively small (six to 10 feet tall and wide) hybrid with highly aromatic spring flowers. Most often grown as a rounded shrub, the shiny, dark green leaves are toothed rather than spiny. Introduced in England in the 1920’s, Burkwood’s osmathus has remained popular for its fragrant early flower clusters and is also reputedly deer resistant.

Planting Osmanthus

Osmanthus is easy to grow and tolerant of an array of conditions, but needs a good start in the garden. Plant potted or balled and burlapped nursery specimens in soil amended with Fafard Premium Natural and Organic Compost. Mulch thoroughly, but do not allow mulch to touch the plants’ main stems or trunks, and water regularly for the first few months while the roots get established.