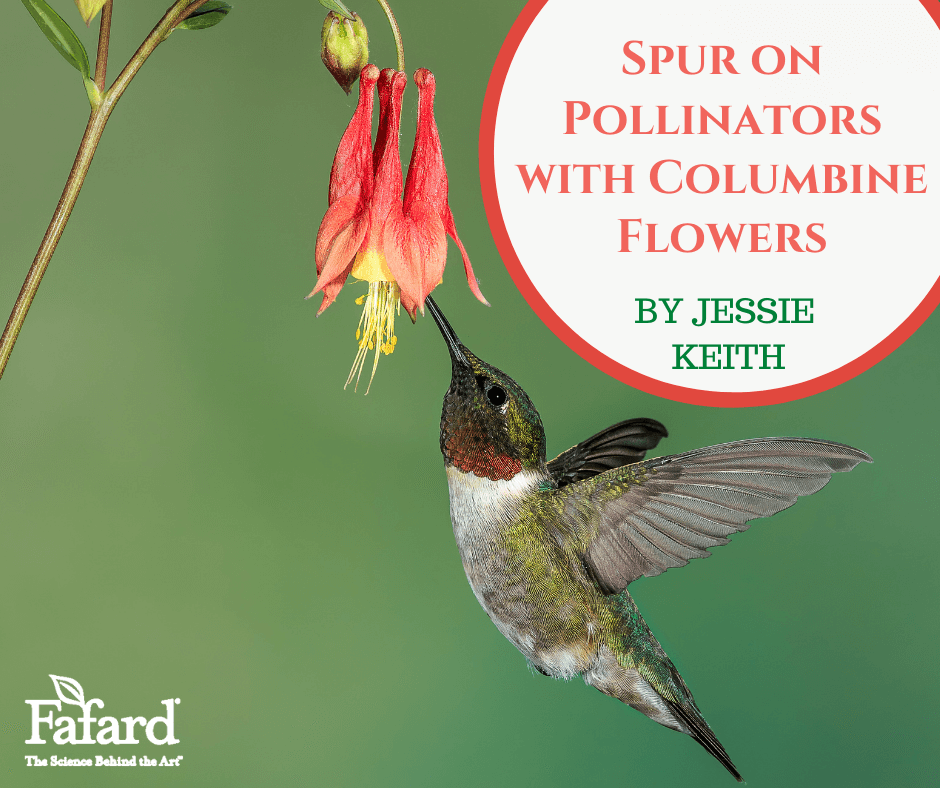

The elegant spurs of columbine (Aquilegia spp.) trail behind each bloom like the tail of a comet. The spurs are elongated, tubular nectaries filled with sweet nectar to feed a variety of visiting pollinators, from hummingbirds to long-tongued bees to hawkmoths. These beautiful perennials are best planted in fall or early spring.

Aquilegia comes from the Latin name Aquila, which translates to “eagle” and refers directly to the flower’s talon-like spurs. They are unique in that many of the 60+ wild species are just as pretty as the hybrids offered at garden centers. All species hail from the North Temperate regions of the world and most bloom in late spring or early summer. The blooms attract pollinators of one variety or another, but many are specially adapted to certain pollinator groups.

Flower color is the main characteristic that dictates pollinator attraction, though spur length, scent, and nectar sugar levels also play a part. Organizing favorite Aquilegia species by color makes it easier to choose the right plants for your pollinator garden design.

Hummingbirds: Red and Orange Columbine

Native American columbine species with red or orange flowers are specially adapted for hummingbirds. Beautiful wildflowers, such as the eastern red columbine (Aquilegia canadensis, 2 feet) with its tall stems of nodding red flowers with yellow throats, or western red columbine (A. elegantula, 1-3 feet) with its straighter, nodding, comet-shaped flowers of orange-red, are sure to attract hummingbirds in spring and early summer. Hummers flying through western desert regions will likely visit the blooms of the Arizona columbine (A. desertorum, 1-2 feet) with its many small, red flowers with shorter spurs. All of these columbine blooms hold lots of extra sweet nectar to fulfill the needs of visiting hummingbirds.

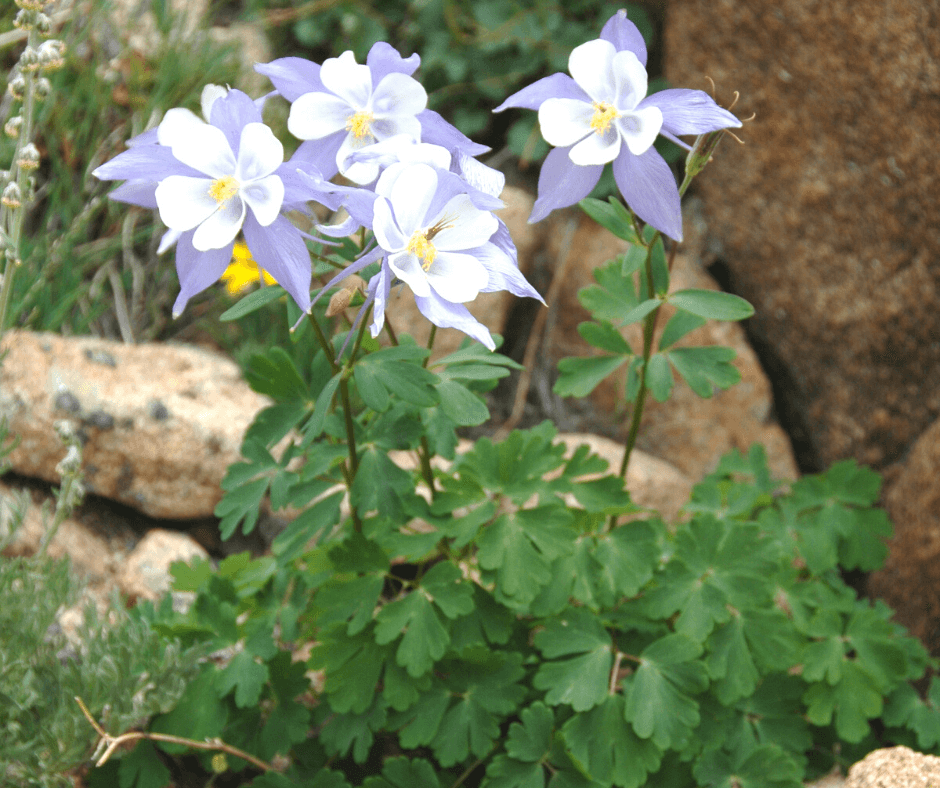

Hawkmoths & Bees: Violet and Blue Columbine

Columbine species with flowers in combinations of violet-blue and white tend to be most attractive to hawkmoths and native long-tongued bees. (Hawkmoths are easily distinguished by their hummingbird-like hovering flight patterns and long tongues adapted for nectar gathering.) Blue columbine with long spurs, such as the Colorado blue columbine (A. coerulea, 1-3 feet), is most attractive to hawkmoths. Smaller, blue-flowered species, such as the alpine Utah columbine (A. scopulorum, 6-8 inches) and small-flowered columbine (A. brevistyla, 1-3 feet), are better adapted to bee pollinators.

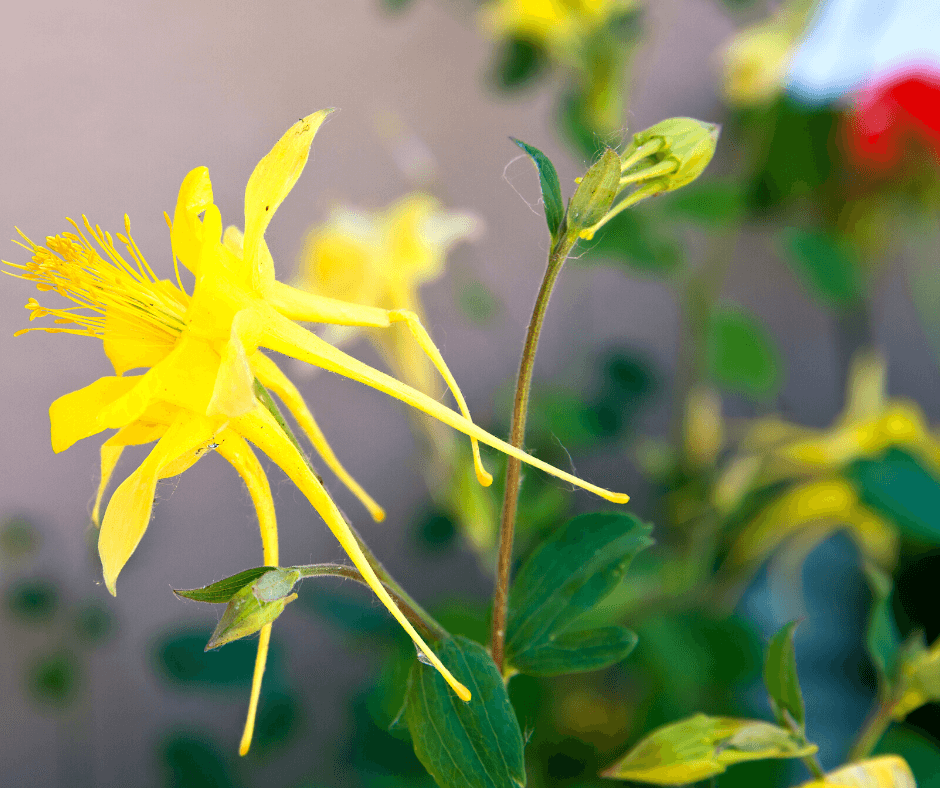

Hawkmoths: Yellow Columbine

Some of the most impressively long spurs are found on columbine with ethereal yellow flowers that glow in the evening light. Most are adapted for hawkmoth pollination. One of the prettiest for the garden is the southwestern golden columbine (A. chrysantha, 3 feet) with its big starry flowers and long, long spurs of gold. From spring to summer the plants literally glow with beautiful blossoms. Another big-spurred beauty from the American Southwest is the long-spurred columbine (A. longissima, 1-3 feet) with its 4-6 inch long spurs. The upward-facing blooms are paler yellow than A chrysantha and bloom from mid to late summer. Both species look delicate but are surprisingly well-adapted to arid weather conditions.

Growing Columbine

As a rule, columbine grows best in full to partial sun and soil with good to moderate fertility and sharp drainage. Fafard® Premium Natural & Organic Compost is a great soil amendment for these garden flowers. They don’t require heavy fertilization and should be protected from the sun during the hottest times of the day. After flowers, plants often die back or develop a ragged look, so be sure to surround them with other full perennials with attractive foliage and flowers that will fill the visual gaps left by these plants. Good compliments are tall phlox, coneflowers, eastern bluestar, and milkweeds.

Columbines are great choices for pollinator gardens, so it’s no wonder that sourcing species is surprisingly easy. High Country Garden sells a western species collection, in addition to the dwarf eastern columbine, and many others. Moreover, columbine self-sow and naturally hybridize, making them truly enjoyable garden flowers for gardeners we well as our favorite pollinators.