Where there’s a sidewalk, there’s often also a hellstrip – that narrow planting space between the walk and the street. Flanked by baking pavement and blessed with soil composed of compacted sand, construction rubble, and the like, it’s not the most welcoming place for plant life. It also confronts unique challenges such as marauding dogs (and humans), traffic visibility restrictions, and road salt. If a plant is over 4 feet tall or can’t handle even a bit of foot traffic or salt spray, it’s probably not suited for hellstrip duty.

As it turns out, quite a few plants native to eastern and central North America are more than up to these challenges. After all, environmental conditions in coastal sand dunes, dry prairies, rocky slopes, and numerous other native habitats can get every bit as hostile as those in your typical hellstrip.

To give your hellstrip border a strong overall visual structure, dot it with shrubs and large perennials planted singly or in small groups. Then fill in the gaps with smaller plants, including generous groupings of ground-covering perennials. In future years, edit seedlings and offshoots as desired.

Native Plants for Hellstrips

Butterflyweed (Asclepias tuberosa)

Monarch butterflies in your neighborhood will flit with joy if you stud your strip with clumps of this tap-rooted, 2-foot-tall perennial. Native to dry sunny meadows and prairies of Central and East North America, butterflyweed (Zones 3-9) will take as much sun and drought as nature throws at it, answering with an early summer display of orange-red to yellow flowerheads. You’ll likely have even more of it next year, thanks to self-sown seedlings. Lots of other drought-tolerant Asclepias are well worth seeking out and growing – especially the spectacular purple milkweed (Asclepias purpurascens, Zones 4-9). It does indeed produce rich rose-purple domes on stems that are taller than those of butterfly weed (to 3 feet or slightly more). As an ornamental, it’s far superior to its vaguely similar cousin common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca), which has duller flowers and a much more invasive habit (and is best avoided unless you want your border to be ONLY common milkweed).

Twilight aster (Eurybia × herveyi ‘Twilight’); heath aster (Symphyotrichum ericoides)

A hybrid of large-leaved aster (Eurybia macrophylla) and showy wood aster (Eurybia spectabilis), ‘Twilight’ (Zones 3-4) spreads relatively rapidly into ground-covering foot-tall swards clothed with narrowly heart-shaped leaves. Thirty-inch stems decked with pale lavender flowers arise in summer, with bloom continuing from early August into fall. A first-great ground cover for drought-prone partially shaded borders, it also does well in full sun. Speaking of asters, prostrate forms of heath aster (Zones 3-9) and its kin can hardly be bettered as ground covers for hot sunny hellstrips. With their needle-like foliage, they do indeed resemble a heath or heather, until their clouds of small daisy flowers open in late summer. The carpeting, white-flowered cultivar ‘Snow Flurry’ is indispensable for covering ground or cascading down a wall.

Coneflowers (Echinacea and Rudbeckia)

Purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea, Zones 4-8) and showy coneflower (Rudbeckia speciosa, Zones 3-9) are a bit too salt-sensitive for many hellstrips. Instead, you might want to opt for Tennessee coneflower (Echinacea tennesseensis, Zones 4-9), a somewhat smaller, more graceful, more salt-tolerant take on purple coneflower, with narrow leaves and blunter, horizontal (rather than drooping) petals. The flowers are the usual echinacean purple, in late spring and summer. Its hybrid ‘Pixie Meadowbrite’ is a wonderful little thing with shocks of narrow leaves which give rise to relatively large rose-pink flowers on 20-inch stems. As for rudbeckias, among the best and most adaptable is ‘Prairie Glow’, a cultivar of Rudbeckia triloba with swarms of relatively dainty burgundy-and-yellow “black-eyed Susans” in summer. At 40 inches tall it’s close to being a stretch for a hellstrip planting, but its height is countered by the airy see-through texture of its inflorescences. The somewhat short-lived plants inevitably self-sow.

Robin’s plantain (Erigeron pulchellus)

Can a native lawn weed also be an unsurpassably useful groundcover? In the case of the cultivar ‘Lynnhaven Carpet’ (Zone 3-9), the answer is an emphatic “yes”. Large handsome rosettes of broad, fuzzy, gray-green leaves pop up here and there, eventually merging into a weed-smothering mass. It’s adorned in spring with numerous pink daisy flowers on 18-inch stems. Even better, ‘Lynnhaven Carpet’ thrives in just about any soil or sun exposure. Less vigorous but cuter is the Robin’s plantain variety ‘Meadow Muffin’, with congested rosettes of crinkly leaves.

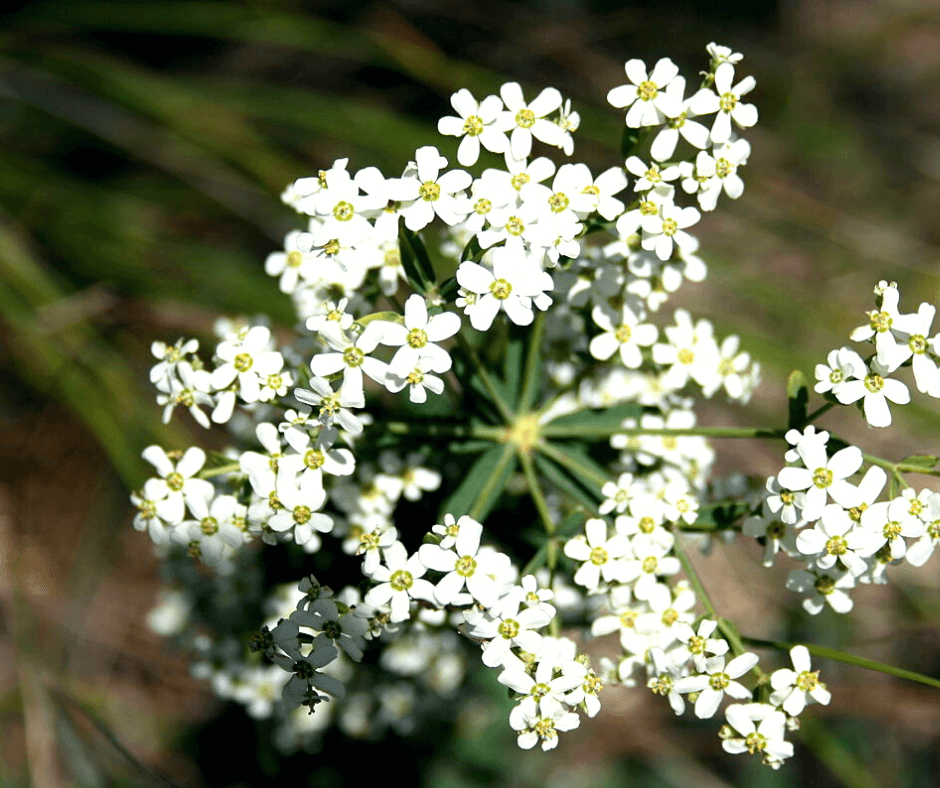

White spurge (Euphorbia corollata)

A delightful prairie and meadow dweller that’s ideal for naturalizing among carpeters such as heath asters, white spurge (Zones 3-9) carries flurries of flowers in late spring and summer that give the impression of a tall baby’s breath (Gypsophila paniculata). It’s a much less fussy critter than any gypsophila, however – provided it has ample sun and elbow room for its sparsely branched, 3-foot-tall stems. It will obligingly seed itself into whatever open patches of soil may occur. Numerous pollinators including the rare Karner’s Blue butterfly adore its flowers, and you’ll also love the vibrant orange and red color of its fall foliage.

Gaura (Oenothera lindheimeri)

This tireless, heat-loving spring-to-fall bloomer was profiled a few months back in our piece on perennials that don’t quit. As with many of the other perennials portrayed here, it will seed itself around in any sunny border, giving you plenty of editing opportunities. White-flowered cultivars such as ‘Whirling Butterflies’ are beautiful things, their waving wands of fluttery white flowers making a pleasing complement to echinaceas and other members of the daisy family. You might also want to mix in a pink-flowered variety (look for ‘Siskyou Pink’ and ‘Crimson Butterflies’).

Little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium)

We dismiss some highly ornamental and useful plants simply because they’re familiar to us as roadside “weeds”. Such is the case with little bluestem (Zones 3-9), which you’ll see ornamenting hot sunny roadsides across most of the U.S. Yet it has many notable charms, especially in late summer and fall, when its tall plumes of purplish-tan seedheads and its sunset-toned fall foliage put on a show. Several cultivars (e.g., ‘Blue Heaven’ and ‘The Blues’) also stand out in summer with their steely silvery-gray leaves. Another to seek out is the tidy, upright, blue-green Prairie Winds® ‘Blue Paradise’. Hot sun and sandy poor soil are no problem – in fact, they’re its preferred habitat.

Seaside goldenrod (Solidago sempervirens)

A plant that naturally grows on sunny seaside dunes and cliffs is ready-made for hellstrip conditions. The mounds of blue-green, tongue-shaped leaves are quietly handsome, and the late summer to fall, 3-foot fountains of sunny flowers are a delight. They’re also a pollinator’s dream (the bumblers, in particular, love them). As with many hellstrip candidates, it actually does and looks best in dry poor soil. It would rather you not pamper it.

Leadplant (Amorpha canescens)

Small shrubs, such as leadplant (Zones 3-8), also have a place in hellstrip plantings. The common name of this 2- to 3-foot shrublet refers to its tolerance of metal-laced soil – and it’s similarly disposed toward road salt. A pulchritudinous prairie native that would flatter any garden, it features ferny pinnate gray-green leaves adorned in early summer with feathery spires of purple-blue flowers.

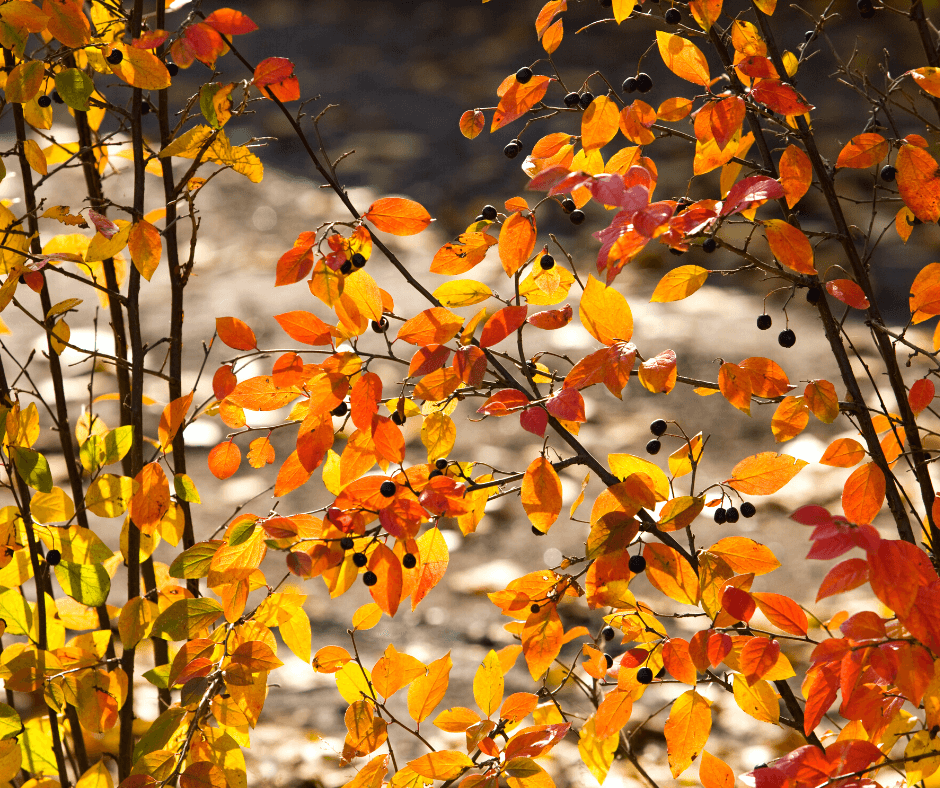

Chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa)

Offering showy white flowers in late spring, edible black fruits in midsummer, and gleaming rich green foliage that goes fiery in fall, compact varieties of this widespread native Aronia (Zones 3-9) are excellent shrubby choices for sunny to partly shaded hellstrips (did we mention that it’s also remarkably adaptable?). Selections include 3- to 4-foot ‘Iroquois’ and the even smaller ‘Low Scape Mound’ (which tops out at 2 feet).

New Jersey tea (Ceanothus americanus)

Here’s another splendid small shrub native to sunny arid habitats in the central and eastern U.S. Its 3-foot stems are covered with frothy white flowers in late spring and early summer, as well as with pollinating butterflies and bees. New Jersey tea (Zones 3-9) also tolerates moist soils.

Planting A Hellstrip

Late summer and early fall are a great time to plan and plant your own native hellstrip border. So why not get to it? If the soil is extremely compacted, sandy, or otherwise plant-habitat-challenged, you might want to fork in a couple of inches of Fafard Premium Natural & Organic Compost or apply it to the surface after planting. Even if you don’t, you’ll find that most of the plants portrayed here will manage to get by in all but the most extreme circumstances. You may sometimes find yourself wondering whether they’re native to the moon, rather than to the North American region of this planet. These babies are tough.