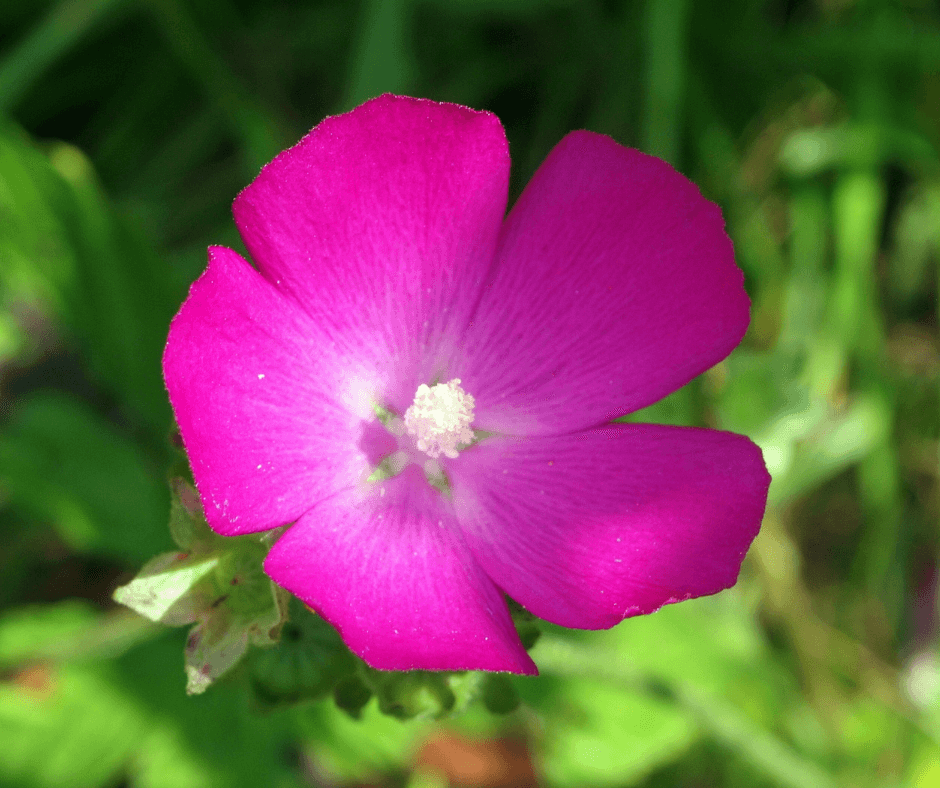

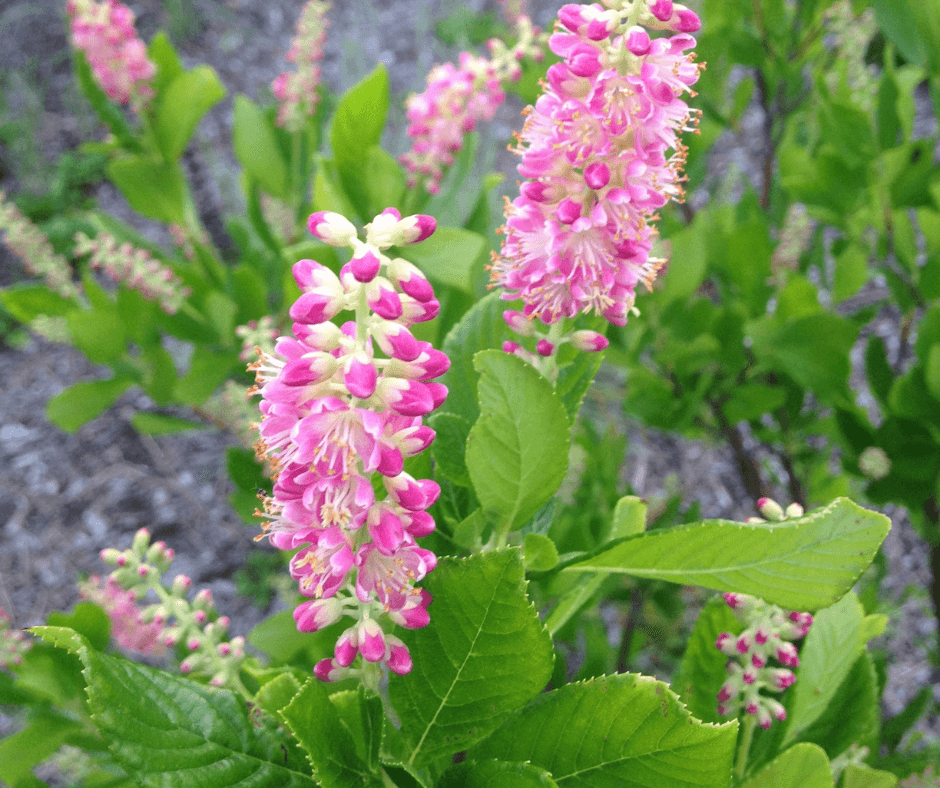

An oceanside garden poses special challenges for plants. The wind-whipped salt-laden air and sandy soil typical of such sites is inhospitable to many sensitive garden favorites, such as border phlox (Phlox paniculata), primroses (Primula spp.), and summersweet (Clethra alnifolia). When faced with these challenging conditions, some gardeners go full denial, erecting barriers to the wind and adding truckloads of humus to the thirsty soil to grow the ungrowable. Such efforts usually end with the realization that defying nature is not a viable gardening strategy.

A more successful approach is to embrace the many rewarding plants that naturally inhabit coastal regions or a streetside garden where winter salt is common. Many of these seaside natives are still not seen in gardens nearly as much as they might be, even in places near the ocean’s roar. They’re also ideally adapted for inland gardens where salt and drought are problems. If sandy soil and salt-happy road crews pose challenges for your garden, coastal natives are among the best answers.

Trees, shrubs, and shrubby ground covers form the core of any garden, coastal or otherwise. Here we highlight 11 of the best such plants that hail from North American seaside habitats. Most offer the added bonus of being favorites of pollinators and other wildlife. As you’d expect, all are happiest in full sun but will tolerate light shade in some cases. Sandy or otherwise well-drained soil is best, with a light mulch of Fafard Organic Compost to help buffer the soil from extreme conditions.

Salt-Tolerant Native Shrubs

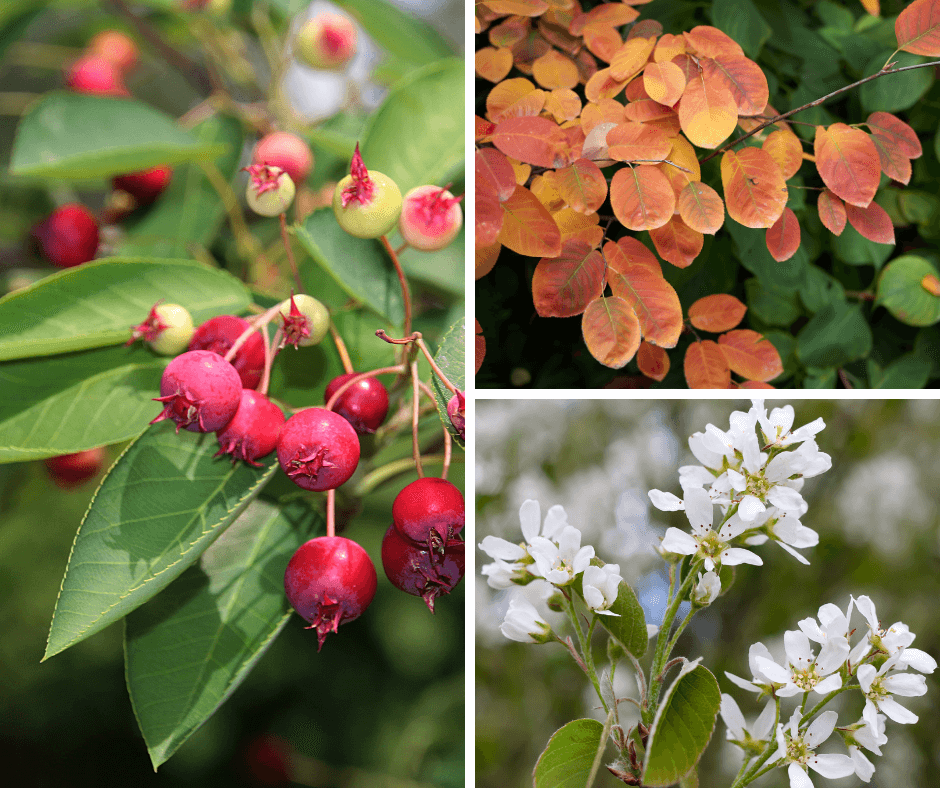

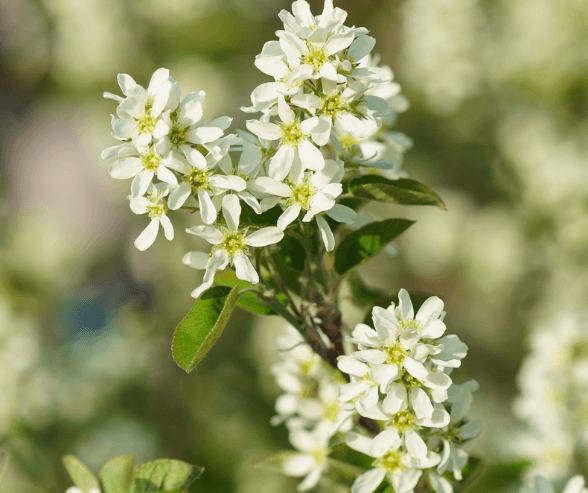

Nantucket Serviceberry (Amelanchier nantucketensis)

Most gardeners know serviceberries as small trees, but this rare East Coast native is a suckering 4-foot-tall shrub. As with most of its tribe, the Nantucket species (Zones 4-8) produces white early-spring flowers followed by edible dark blueish berries that ripen in late spring and early summer. Its close cousin running serviceberry (Amelanchier stolonifera) will also do in a pinch. Both can be hard to find in nurseries. Look for native plants in coastal regions from Nova Scotia to Virginia.

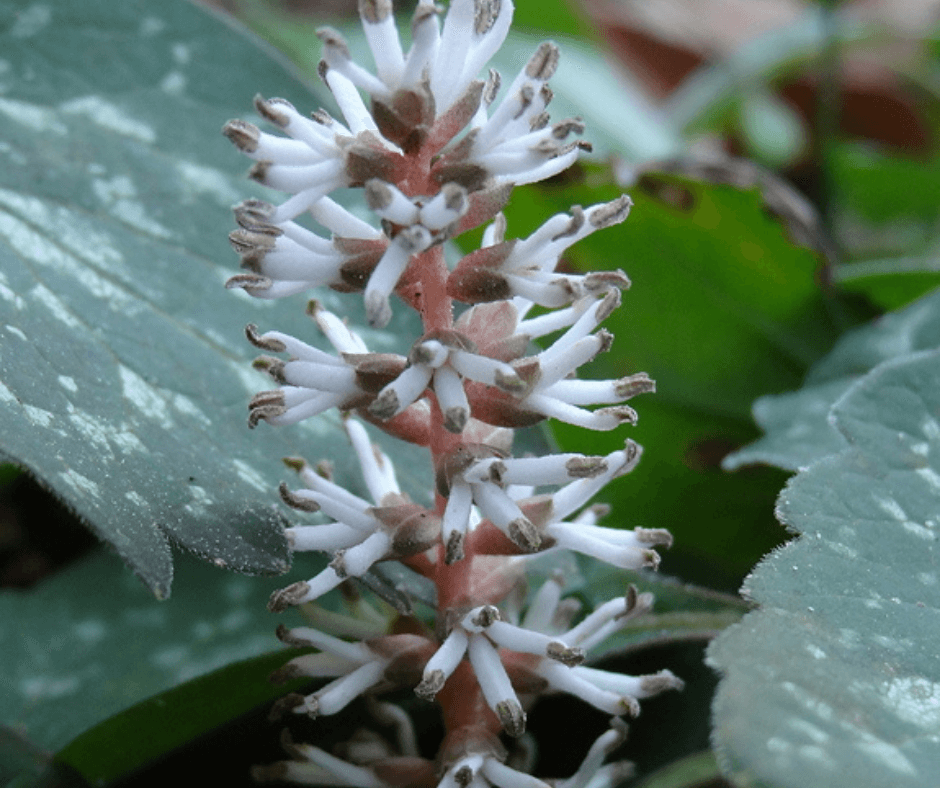

Bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi)

Spreading tufted mats of small rounded evergreen leaves give rise to pinkish urn-shaped flowers in spring, evolving to ornamental red berries in late summer. Even in the poor sandy soils bearberry (USDA Hardiness Zones 2-7) prefers, the groundcover shrub can take a while to settle in, so it’s not for gardeners in a hurry. The natural distribution of the shrub includes the upper latitudes of North America and Eurasia.

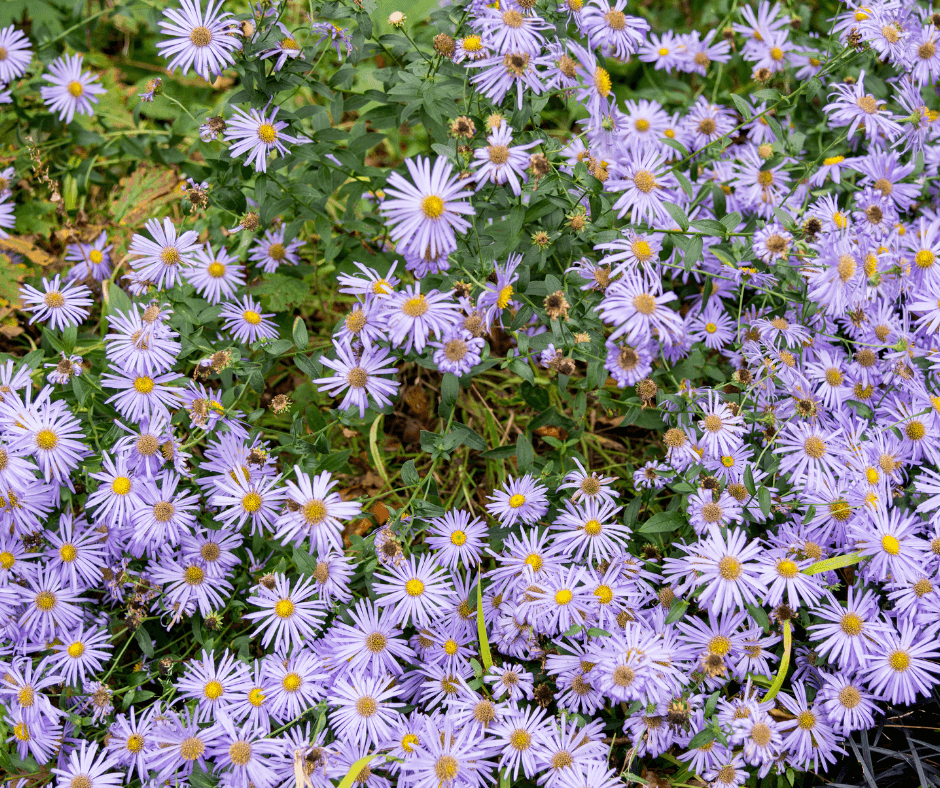

Groundsel Bush (Baccharis halimifolia)

Most hardy members of the aster family are herbaceous perennials, dying back to the ground every winter. Groundsel bush (Zones 5-10) is anything but, forming an upright medium to large shrub – up to 15 feet tall and wide in moist fertile soil. Its growth is relatively restrained in dry sandy conditions. Clad in attractive shiny bright-green foliage from spring until late fall, Baccharis halimifolia takes center stage in late summer, engulfing itself in clouds of small white flowers. Female plants go a step further, producing downy silvery seedheads that glisten in the slanting late-season sunlight. The seeds drift away in late fall, often producing a large crop of progeny – so you and your neighbors will need to be on the lookout for possible unwanted seedlings. The shrub’s native distribution is from Massachusetts to Texas.

Inkberry (Ilex glabra)

Inkberry (Zones 4-9) has become a staple evergreen shrub for sunny and lightly shaded gardens throughout much of the US. This is largely thanks to the introduction of compact varieties such as ‘Shamrock’, ‘Green Billow’, and ‘Forever Emerald’, which maintain a dense compact habit rather than becoming sparse and rangy like the straight species. The glossy spineless dark-green leaves are joined by small white flowers in spring, and on female plants by little black berries in fall. The cultivar ‘Ivory Queen’ is showier in fruit, bearing pearly white fruit. The native distribution is from Nova Scotia to Louisiana.

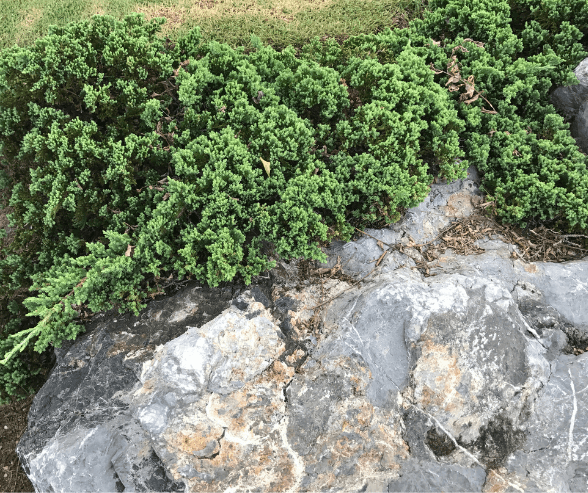

Creeping Juniper (Juniperus horizontalis)

Even the most casual gardener is likely to be familiar with this garden workhorse, whose prostrate scaly-leaved evergreen branches provide ground cover in many a sunny garden niche. Plants often turn bronze-green in winter. Numerous varieties of creeping juniper (Zones 3-8) are available, including vigorous blue-tinged ‘Wiltonii’ (commonly known as blue rug juniper), and ground-hugging, fine-textured ‘Bar Harbor’. The native distribution is across temperate North America.

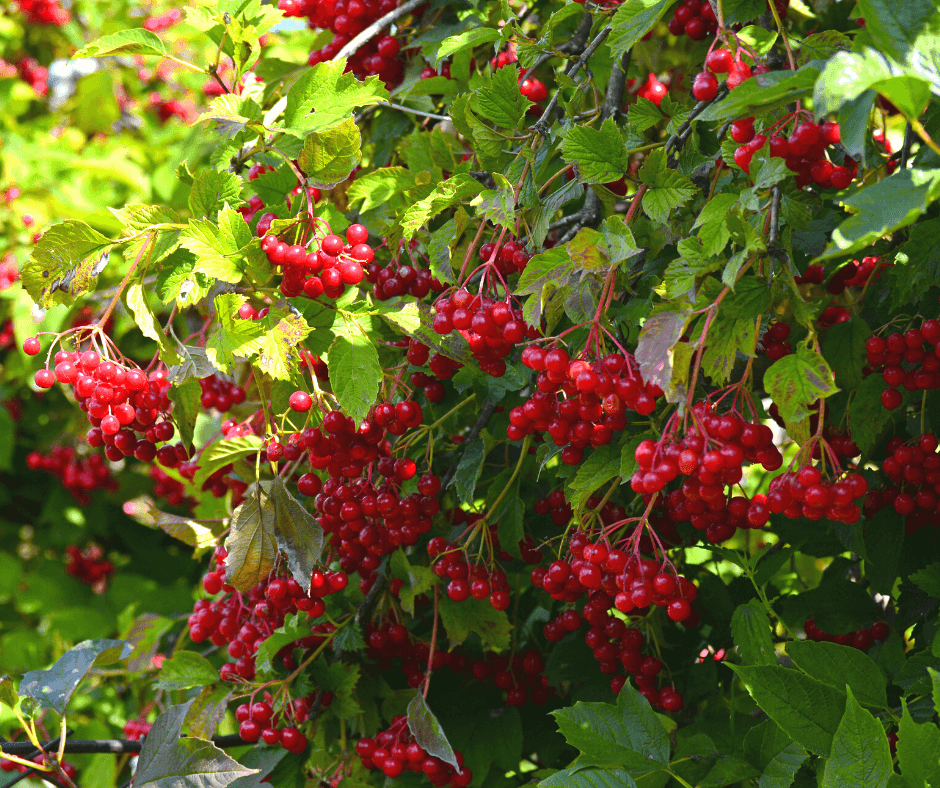

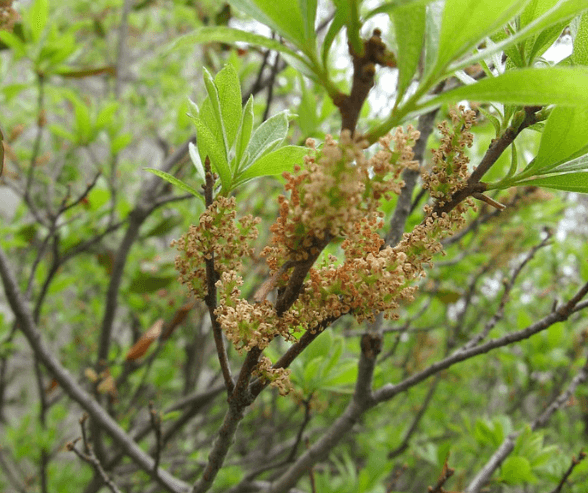

Northern Bayberry (Morella caroliniensis)

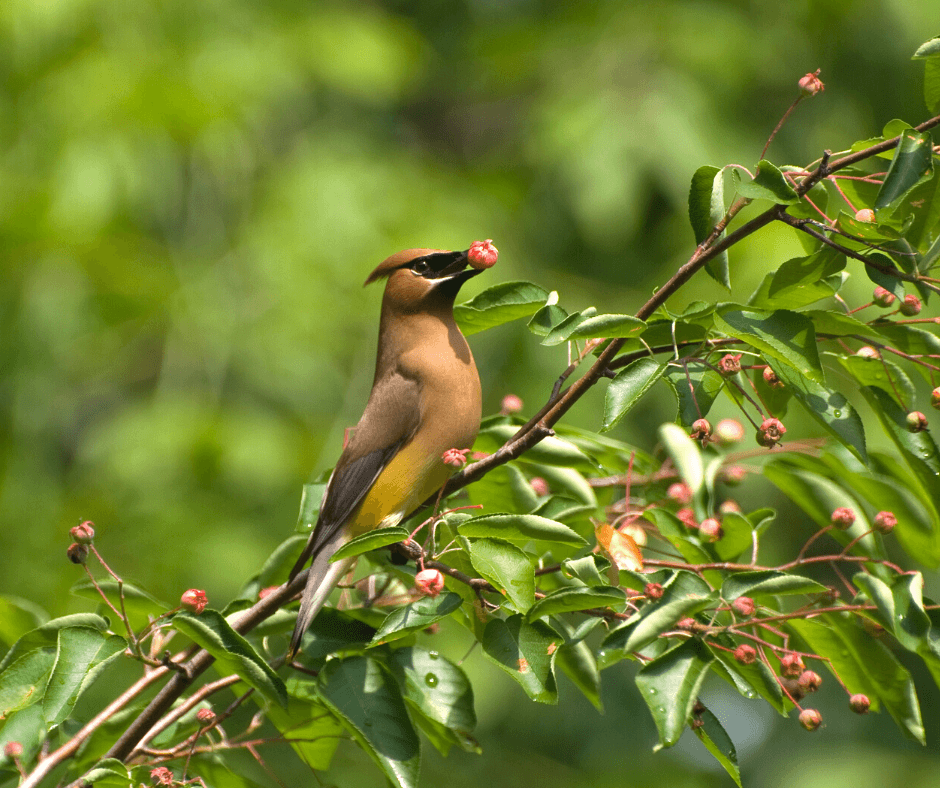

Long prized for its glossy aromatic semi-evergreen foliage and its winter berries, northern bayberry (Zones 3-7) spreads gradually into somewhat sparse 6- to 8-foot thickets that work well as informal hedging. Cedar waxwings, yellow-rumped warblers, and other birds hungrily harvest the berries in late winter. Both male and female plants are required to produce the fruits, which were traditionally used to scent bayberry candles. The shrub exists from Newfoundland to North Carolina.

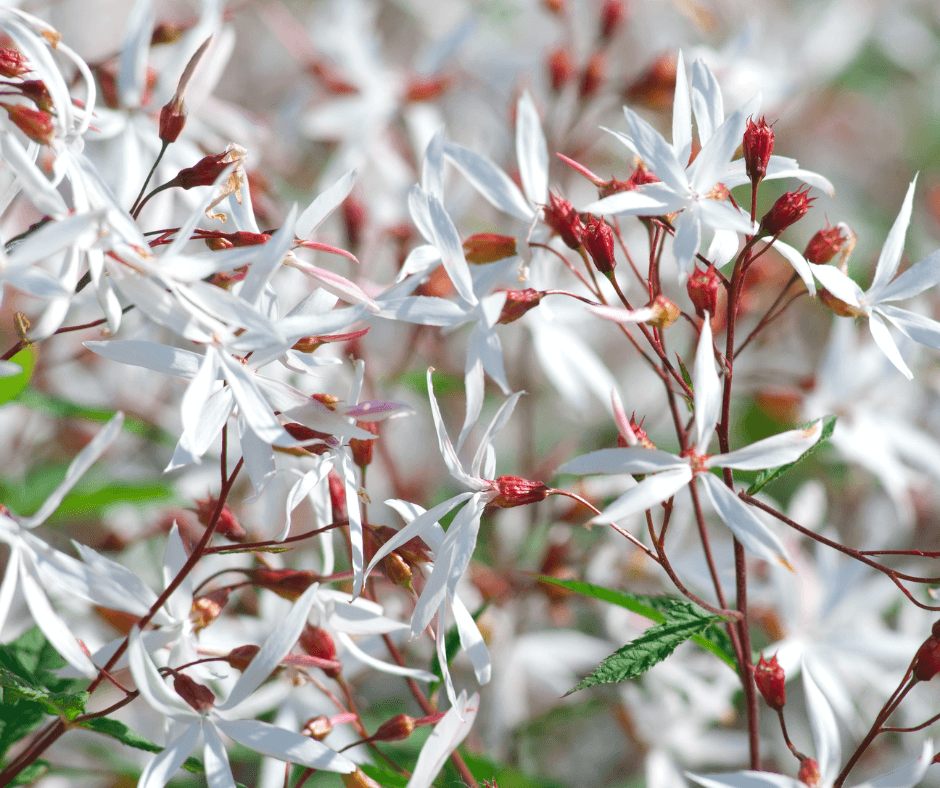

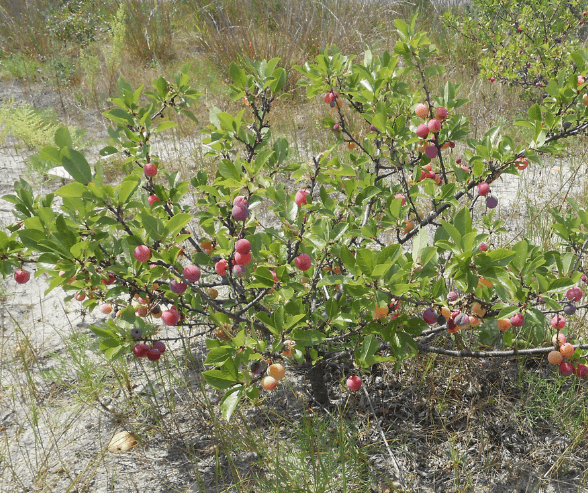

Beach Plum (Prunus maritima)

The tart, grape-sized fruits of Prunus maritima (Zones 4-8) excel in preserves, syrups, vinegars, and jams. Beach plum fanciers typically harvest them from the wilds of the Atlantic coast when they ripen in late summer. Plant a few female beach plums along with a pollenizing male, and you’ll have a harvest right outside your door. Although a rather scraggly 3- to 5-foot thing in its native dune habitats, beach plum forms a dense, attractive 6- to 10-foot shrub under garden conditions. Swarms of snowy white flowers in spring are a further ornamental feature. Most plants bear irregularly from year to year, so look for selections – such as ‘Snow’ and ‘Jersey Beach Plum’ – that are more consistent producers. Cultivars ‘Nana’ and ‘Ecos’ bear reliable annual crops on more compact 3- to 5-foot-tall plants. You can further enhance beach plum’s productivity and habit by thinning out old, unproductive branches in early spring. Beaches from Maine to Virginia are home to the shrubby plum.

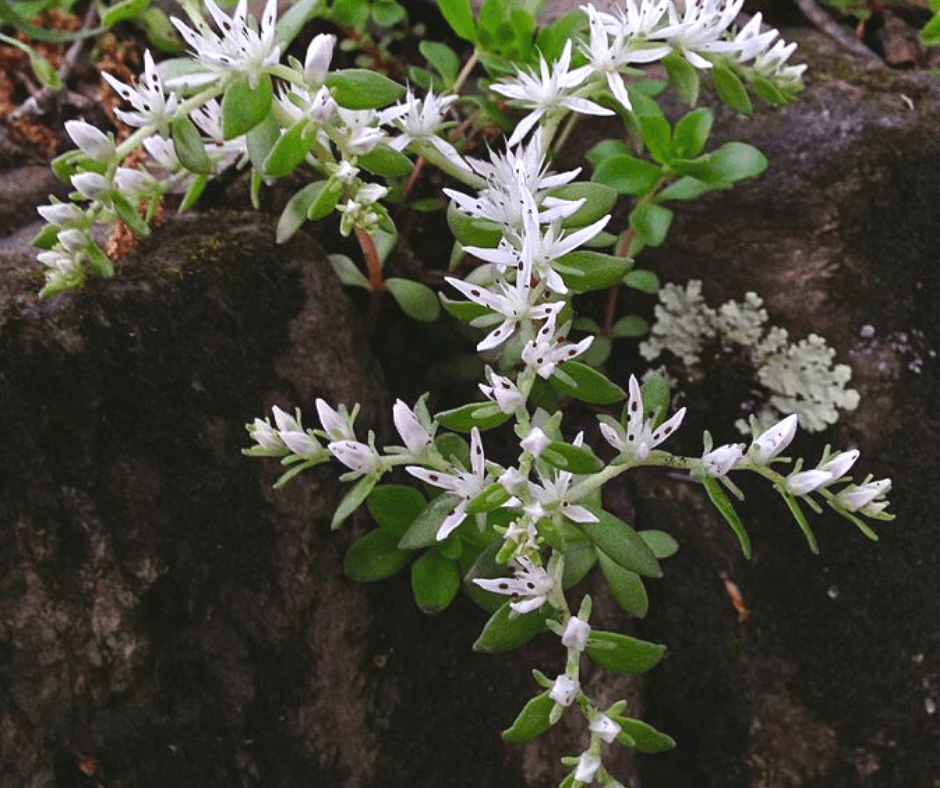

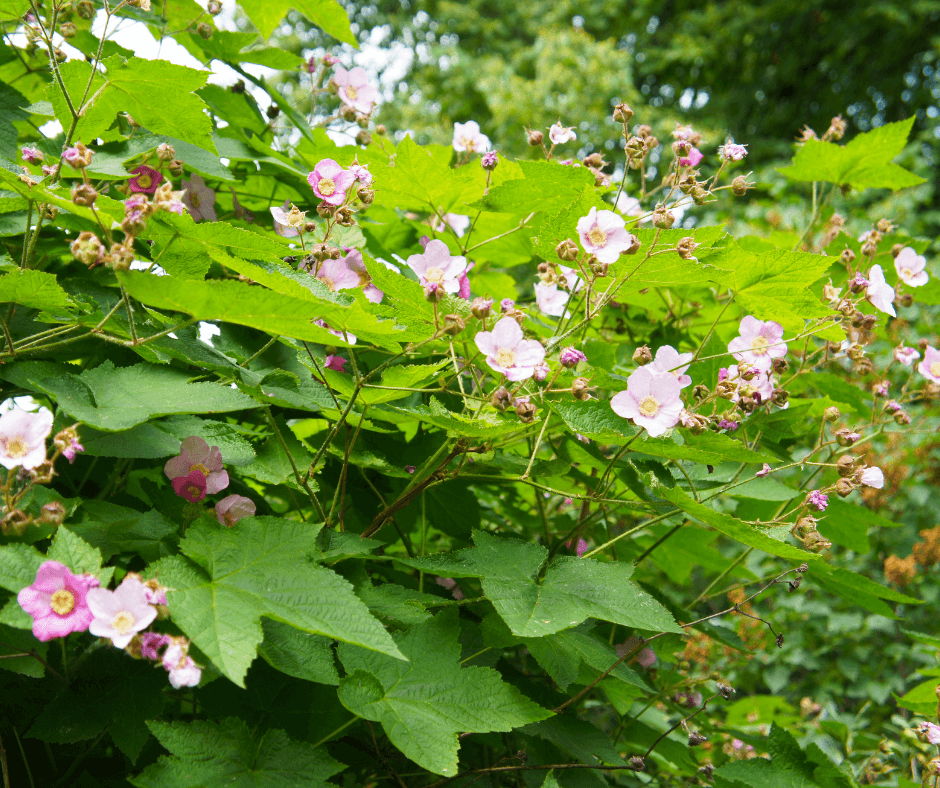

Dwarf Sand Cherry (Prunus pumila)

Edible fruits are also a feature of the outstanding 2-foot tall ground cover cherry (Zones 3-8), which will quickly cover a sandy bank with its sprawling stems. The summer-ripening fruits are preceded by white flowers in spring. Dwarf sand cherry can be found along coasts from Ontario to Virginia.

Salt-Tolerant Native Trees

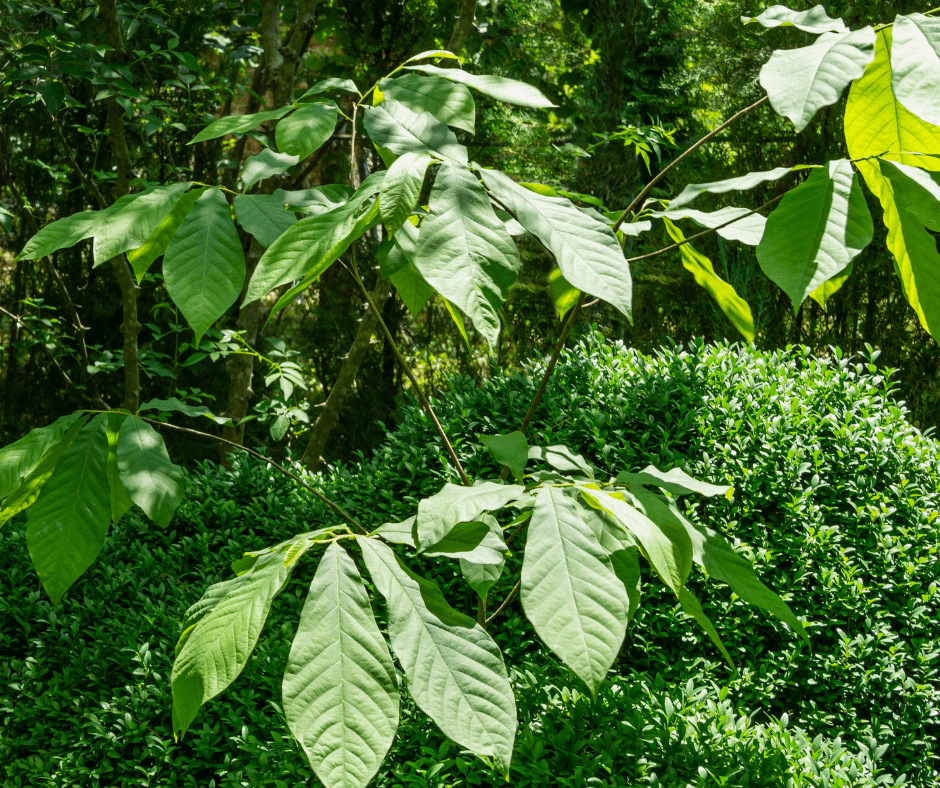

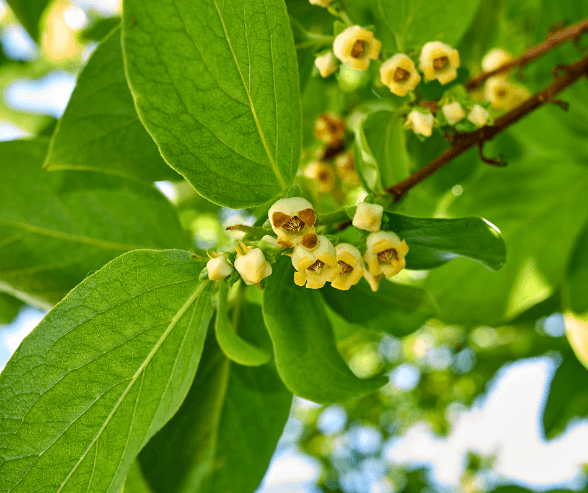

American Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana)

A must for the edible coastal garden, this Connecticut-to-Texas native does indeed bear tasty persimmons (Zones 5-10). Ripening orange in fall, the squat, tennis-ball-sized fruits mellow from astringent to tartly flavorful as they soften. A tree in full fruit gives the appearance of being laden with miniature pumpkins. You’ll need both male and female trees – or a self-pollinating selection such as ‘Meador’ – to get fruit. American persimmon matures into a large picturesque open-branched tree with handsome, plated, charcoal-gray bark and bold, oval, deciduous leaves. Few trees can match it as a four-season ornamental.

American Holly (Ilex opaca)

If you’re looking for a classic spiny-leaved, conical, tree-sized holly (Zones 5-9), here’s the native for you. Growing slowly to 20 feet or more, it maintains a dense, fully branched habit in sunny sites. Partially shaded specimens are sparser and lankier. With its signature shape and its red berries from fall into winter, American holly makes an arresting feature plant. It also works well as an impenetrable barrier hedge. Selections that depart from the norm in size, fruit or leaf color, or other characteristics are also available. Look for the holly in native lands from Massachusetts to Texas.

Pitch Pine (Pinus rigida)

The signature species of pine barrens and other sandy habitats in eastern North America, Pinus rigida (Zone 3 to 8) typically grows as a somewhat gnarled small to medium-sized tree. It can attain considerable height in more fertile habitats. Best for gardens is ‘Sherman Eddy’, a superior dwarf cultivar, which forms a rounded, 12- to 15-foot specimen with densely needled, bottlebrush-like branchlets. Even more dwarf is ‘Sand Beach’, a mounding prostrate selection. Look for the tree from Maine to Georgia.