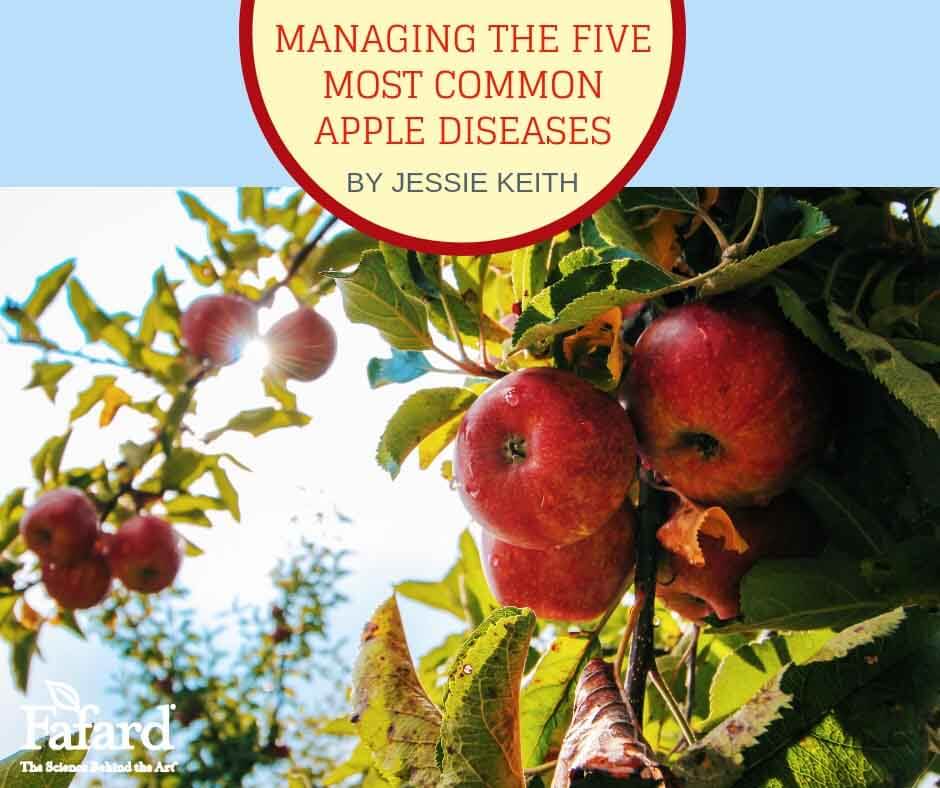

Don’t be afraid to grow your own apples. Sure, most varieties are rife with disease problems, but there are varietal exceptions, and smaller trees make management easier. Choosing disease-resistant apples and understanding care requirements will make for a reliably healthy harvest. Aspiring orchardists need not be discouraged.

Before and after steps can be taken to ward off common apple diseases. Preliminary steps include planting and caring for your trees correctly and applying preemptive horticultural oils and other natural pesticides. After problems appear, there are other sprays for disease management. To understand what steps to take, a gardener must be able to identify and understand each disease for management.

Five Common Apple Diseases and Management

Apple Anthracnose (Neofabraea spp.): Cool, wet weather encourages this fungal disease that causes reddish or orangish circular cankers on the bark, which can open to show the interior wood. Leaf spots and bull’s-eye fruit rot are also expected features. The disease is rarely deadly. Solution: Use a strong copper-based fungicide during a rain-free spell at spring bloom and just before harvest. Remove and burn cankered branches and stems when plants are dormant in winter.

Cedar Apple Rust (Gymnosporangium juniperivirginianae): When trees are infected, orange spots develop on the leaf tops with odd-looking brownish fungal spikes below. The spots weaken trees. Infected cedars and junipers spread the disease to apples, pears, and other related hosts, so fruit growers must avoid planting these evergreens. Solution: Apply a fungicide for rust, such as Neem oil, when the trees are in bloom if a tree has shown signs of the disease in the past.

Fireblight (Erwinia amylovora): Fireblight is an easily identifiable bacterial disease that’s spread when it’s rainy. It gives leaf tips, flowers, and stem tips a scorched look. Stem tips curl as they die. Infected leaves dry up and turn brown or black. Badly infected trees develop cankers with orangish bacterial ooze on branches and twigs. Solution: Remove and burn branches with signs of the disease when plants are dormant in winter. If weather conditions are moist at bloom time, spray them with a fireblight bloom spray. Throughout the season, look for the early onset of symptoms and cut and burn infected stems as they appear.

Apple Scab (Venturia inaequalis): Both fruits and leaves are damaged by this fungal disease. Apple scab overwinters on leaf buds and shows itself when weather conditions become warm and moist. Leaf spots are green and velvety and then turn black. Eventually, whole leaves succumb and die. Infected fruits have scab-like cracked or bulbous spots. Solution: Apply copper fungicide spray or Bonide® Citrus, Fruit & Nut Orchard Spray, according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, just before bud break and through to early fruit set.

Powdery Mildew (Podosphaera leucotricha): Warm, moist or dry weather favors this fungal disease. A powdery substance cover young leaves and new shoots, causing them to crinkle and curl. Solution: Apply the all-natural, potassium bicarbonate-based Greencure® foliar fungicide spray until symptoms are gone.

Note when you spray different pesticides. For example, copper fungicide sprays should be applied 10 days after an application of dormant oil spray. Use home pressure sprayers for application. (Click here to learn more about horticultural soil sprays and their use.)

Disease Resistant Apple Varieties

Disease-resistant apple varieties and root stocks make control much easier. Different root stock varieties can also impart vigor and productivity. Tree size is also dictated by the rooting stock, resulting in dwarf, semi-dwarf, or mid-sized trees. (Even the smallest garden can accommodate a couple of dwarf apple trees in large pots or espaliered against walls.) Nursery-purchased apple trees are generally grafted onto good stock with just tree size being variable. (Click here to learn more about apple root stocks.)

Newly cultivated apples are bred for disease resistance as well as flavor. These are the best apples to grow organically because they require little to no spray. Sadly, most heirlooms are very disease susceptible, though a few show some resistance. The 19th-century cultivar ‘McIntosh’ (19th century) is resistant to cedar apple rust and powdery mildew, and ‘Winesap (18th century) is resistant to cedar apple rust. Here are five of the best newer disease-resistant varieties available:

- CrimsonCrisp™: A sweet, crisp apple with deep red skin that’s highly resistant to apple scab and moderately resistant to fireblight and powdery mildew.

- ‘Enterprise‘: A firm, crisp, tart red apple with high resistance to apple scab and moderate resistance to cedar apple rust and fireblight.

- ‘Goldrush‘: A tangy, sweet golden apple with high resistance to apple scab and moderate resistance to fireblight.

- ‘Jonafree‘: A flavorful, low-acid, red apple that bears heavily and is very resistant to apple scab.

- ‘Liberty‘: A yellow and red apple that’s crisp, sweet, tart and shows great resistance to apple scab, cedar apple rust, fireblight, and powdery mildew!

All apples require cross-pollination, so you need to plant yours with compatible varieties for fruit set. (Click here to view compatible apple varieties for cross-pollination.)

Planting and Care

Plant apples in spring or fall. You can buy either nursery or online stock. Trees purchased online will be smaller and take longer to establish.

At planting time, dig a hole to the same depth as the root ball and three times as wide. Place the backfill on a large tarp or in a wheelbarrow and mix it with Fafard Premium Natural and Organic Compost at a 1:2 ratio. Sprinkle in an all-purpose tree fertilizer, using the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Center and hold the tree straight in the hole. Make sure the top of the root ball meets the lawn’s soil line. Then plant it with the amended backfill and tamp it in to remove air pockets. Water deeply after planting, filling in any low spots as they appear, and then add 2 to 3 inches of bark mulch or compost around the newly planted tree. Continue watering one or two times a week for at least two months during dry spells.

Good apple selection and disease management will leave growers with few disease worries. Apple pests are another matter, but they are often far less destructive if populations are low to moderate. Planting compact apples will make care even easier. So be daring and plant one or more apple trees this fall.