Totally On-Trend

If you wanted to create the most on-trend garden for the new gardening season, what would it look like? Leafing through shelter magazines, garden catalogs, websites, and other communications outlets, it would appear that a totally on-trend garden might exist in either in-ground or container form and contain a wide array of drought-tolerant annuals, perennials, and shrubs with jewel-toned flowers and the ability to attract an abundant number of pollinators. Extra trend points would go to those landscapes featuring native plant varieties with excellent resistance to extreme weather. For gardener’s living in areas prone to wildfires, all of the above would happen in the context of fire-awareness, with vegetation-free shelter belts around houses and other structures.

Pollinators’ Heaven

While many garden merchandisers are offering pre-selected pollinator gardens, it is fun to pick individual varieties on your own. Members of the mint family are much loved by butterflies, moths and other insects, and in the last few years, hummingbird mint or agastache has ridden a wave of popularity. Many are drought tolerant as well. New agastaches this year include colorful additions to the Maestro® Agastache series like ‘Gold’ and ‘Coral’. Catmint, a stalwart of easy-care perennial landscapes, is newly available in a gold-leafed variety, ‘Lemon Purrfection’.

Hydrangeas Hold Court

The enduring popularity of hydrangeas, especially new varieties that bloom on both new and old wood, is on display in this season’s new offerings. Rich color dominates in offerings like the red-flowered hydrangeas, with Hydrangea macrophylla Seaside Serenade® Hanalei Bay and Centennial Ruby™ leading the way. Smaller hydrangea offerings, suitable for small landscapes and even large containers abound, with varieties like compact ‘Lil Annie’ oakleaf hydrangea leading the way

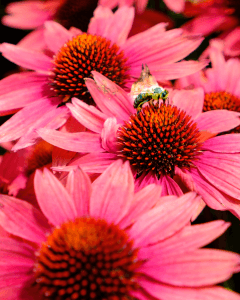

Coneflowers in Every Color

If coneflowers (echinacea) are not in every single garden, container and window box in America and elsewhere, it is not for lack of variety. Echinacea has been hotter than hot for more than a decade and the heat persists. New bi-colors, like ‘White Tips’, with lavender petals edged in bright white, increase the color possibilities, while double-flowered ‘Raspberry Ripple’ adds yet another entry in the fluffy flower category. The trend for unusual petal configurations—quilled, spoon-shaped, or spidery—has resulted in echinaceas like ‘Prima Spider’, a bi-colored variety with slender spoon-shaped petals.

Cavalcade of Dashing Annuals

Breeders and merchandisers are working hard to keep up with the demand for ever more colorful annual bedding plants. New entries into the annual array include ever brighter shades of impatiens, petunias (and their relatives the “million bells” or calibrachoa) in single and double varieties, some with extravagant stripes. Unusually colored petunias like Amazonas™ ‘Plum Cockatoo’ change the garden color scene with pale green petals swirling around purple centers. Not to be outdone, new members of the Queeny series of lushly petalled and colored Zinnia elegans varieties includes opulent double-flowered entries like ‘Queeny Red Lime’, a bi-color with rose pink outer petals surrounding shorter, lighter inner petals. Other unusual colors include ‘Queeny Lemon Peach’ and ‘Queeny Orange’.

For color in shade, gardeners have long turned to the flashy foliage of annual coleus. This year’s newcomers include ‘Pink Ribbons’, with toothed, near-black leaves edged and veined in bright pink.

Dahlia Resurgence—Hang Onto Your Tubers

Once reviled as common and kitschy, dahlias now take center stage everywhere, with lots of new entries for spring 2026. One old reliable vendor lists no fewer than 16 online pages of new varieties. New and noteworthy entries in the dahlia sweepstakes include the fluffy, exuberantly striped ‘Knight’s Armour’ and the demure ‘Halo’. Popular introductions routinely sell out, so if growing dahlias from tubers is your thing, order now.

Houseplant Riot

For apartment dwellers and those lacking outdoor space, garden merchandisers say, “no problem”, and back that up with an amazing area of houseplants (which can be moved outside, space and climate permitting). The world of fancy-leaf begonias has expanded with new entries including ‘Joy’s Jubilee’, an exuberant swirl of ruffled green and maroon leaves, dappled in white. Foliage plants—restful and otherwise—are also very popular, especially in large sizes, with new introductions like the elephant-eared Alocasia ‘Variegated Freydek’, flaunting its huge green and white leaves, or white variegated monstera, with its artfully tattered foliage. Old-fashioned parlor maples (Abutilon) have shed their Victorian image and reappeared in new forms, like ‘Red Glory’, with scarlet hollyhock-like flowers, and the pink and white ‘Wedding Day’, which celebrates its name with nodding blooms.

Drought Tolerant

With drought conditions a regular occurrence in some parts of the country, gardeners are looking for deep-rooted prairie plants like goldenrods and penstemons that need little hydration once they are established. Where climate permits, or indoor winter quarters exist, agaves are very much in vogue, with new introductions like the variegated ‘Craziness’ or the gold and green striped ‘American Masterpiece’, an agave/mangave hybrid.

Newcomers Welcome

Garden vendors are especially interested in attracting new gardeners to the hobby. For them, the merchants have created an increasingly wide array of pre-planned gardens, sold complete with plants and planting diagrams. Container gardeners are not left out of this trend, and companies with provide plants, diagrams or pictures, and selected containers, making plant selection and arrangement easy and accessible. The packages may or may not include the newest or most fashionable plants, but they are designed to encourage the novices who will buy the new introductions of the future.