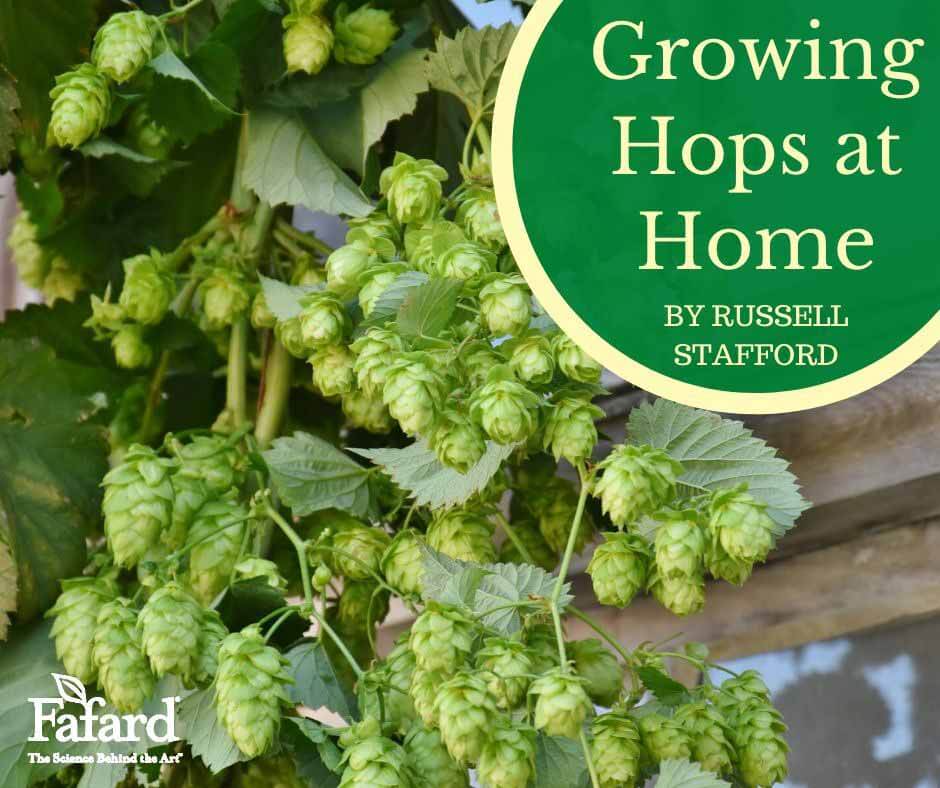

If you’re into brewing your own beer, perhaps it’s time to start growing its components, too. Hops – the cone-like fruits that give most brews their signature flavors and aromas – are a cinch to cultivate if you have lots of vertical garden habitat such as a pergola or large trellis. A close relative of “weed” (it’s a member of the Cannabis family), hops (Humulus lupulus, USDA Hardiness Zones 5-10) is something of a weed itself, twining to 15 feet or more in spring and summer and dying back to a suckering perennial rootstock in winter. You’ll sometimes find it winding through the abandoned shrubbery of pre-revolutionary estates, a legacy of a time when home-grown and home-brewed beer was a way of life.

Hops Flowers

Hops are borne on female plants of Humulus lupulus – no male companion required. In fact, growers and brewers generally shun male plants, preferring the flavor of seedless hops. No nearby males mean no pollination and thus no seeds. Occasionally, female plants may produce conical sprays of small sterile flowers that appear to be male. These ersatz male flowers are pollenless.

Growing Hops

Humulus lupulus plants flourish in full sun and fertile, moist, organic-rich soil. Dig a planting hole several times wider than the root ball, and amend the backfill with Fafard Organic Compost, as needed. If indicated, topdress your newly planted hops with a fertilizer relatively high in nitrogen and potassium and low in phosphorous (5-2-4 works well). Mulch with a couple inches of compost, and your hops are good to grow. Water frequently during late spring and early summer, when the hops vines (or “bines”, as they’re traditionally known) are growing most rampantly – as much as 9 inches per day. You can also propagate hops from seed, rogueing out male seedlings as they flower.

Hop Varieties

Numerous of hops varieties are available from specialty growers. (Click here for the hops list.) The fruits of each variety possess characteristic levels of acids and other compounds that determine the bitterness, aroma, and other qualities of the hops – and of your brew. All have comparable growth habits. The real differences are in the fruits. One variety – Humulus lupulus ‘Aureus’ – is grown for its ornamental yellow foliage rather than for its hops.

Across Eastern North America, Japanese hops (Humulus japonicus) has become a nasty invasive species with no beer-making value because the flowers lack the pleasing flavors favored for beer. One distinctive characteristic is that the leaves and stems are covered with scratchy spines. The female flowers are also very small. Pull these plants on sight because they terribly invasive vines can reach 35 feet in a season and cover beds and landscape areas quickly.

It’s best to purchase hops as container-grown plants propagated from disease-free stock. Hops were traditionally propagated from sections of root-like rhizomes, but rhizomes sometimes carry viruses and other diseases.

Harvesting Hops

Hops ripen in late summer – August or September in most of their USDA Zone 4 to 9 hardiness range. Plants may not bear well their first year or two. Harvest the hops when their outer scales begin to feel dry, papery, and slightly springy to the touch, and when their powdery coating (known as “lupulin”) turns yellow and sticky. You can either pluck the hops off the standing vines, or cut the plants back to 3 feet and harvest the hops from the cut vines. In either case, wear gloves and thick clothes to protect your skin from the bristly, irritating hairs that coat the plants.

Either use the freshly harvested hops in your brew, or spread them out to dry on a screen or in a food dehydrator or 140 degree oven. Dried hops are ready to store when they’re papery and slightly brittle, and when their lupulin sheds readily from the scales. Bag and freeze the dried hops to use in future brews.