In the time of Roman Emperor Julius Caesar, “divide and conquer” was a battlefield technique that defeated the Emperor’s enemies and expanded the Roman Empire. You can expand your own empire—or at least your supply of ornamental plants—by dividing mature clumps of perennials. This technique, which does not require much in the way of labor or expertise, will also revitalize established perennials and improve the looks of your garden.

Perennials for Division

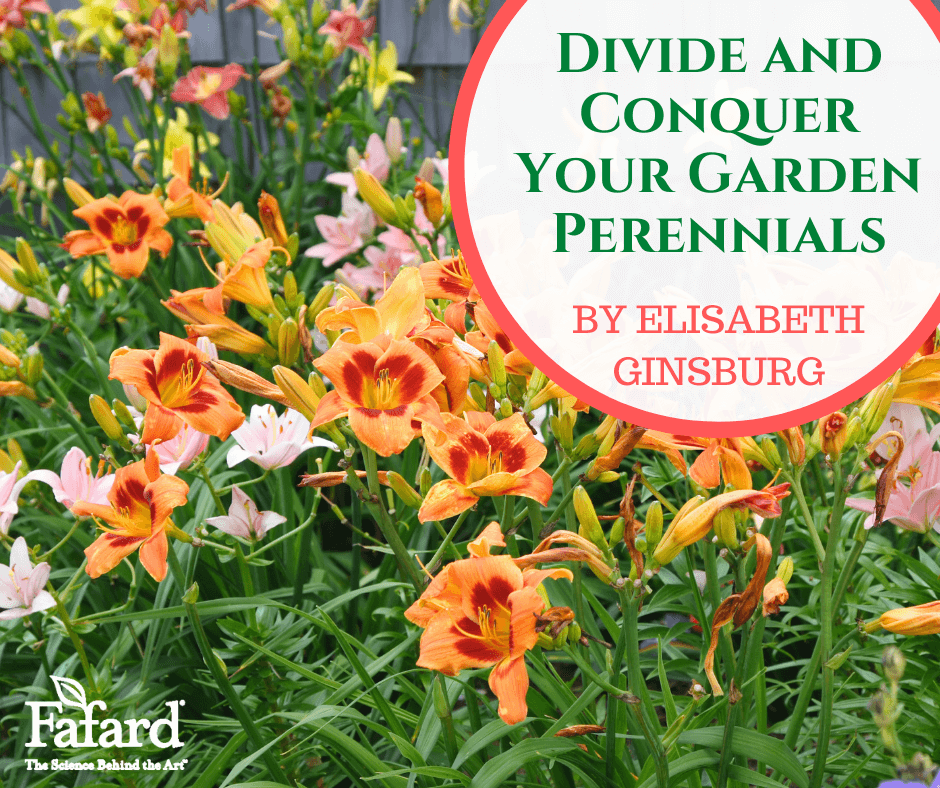

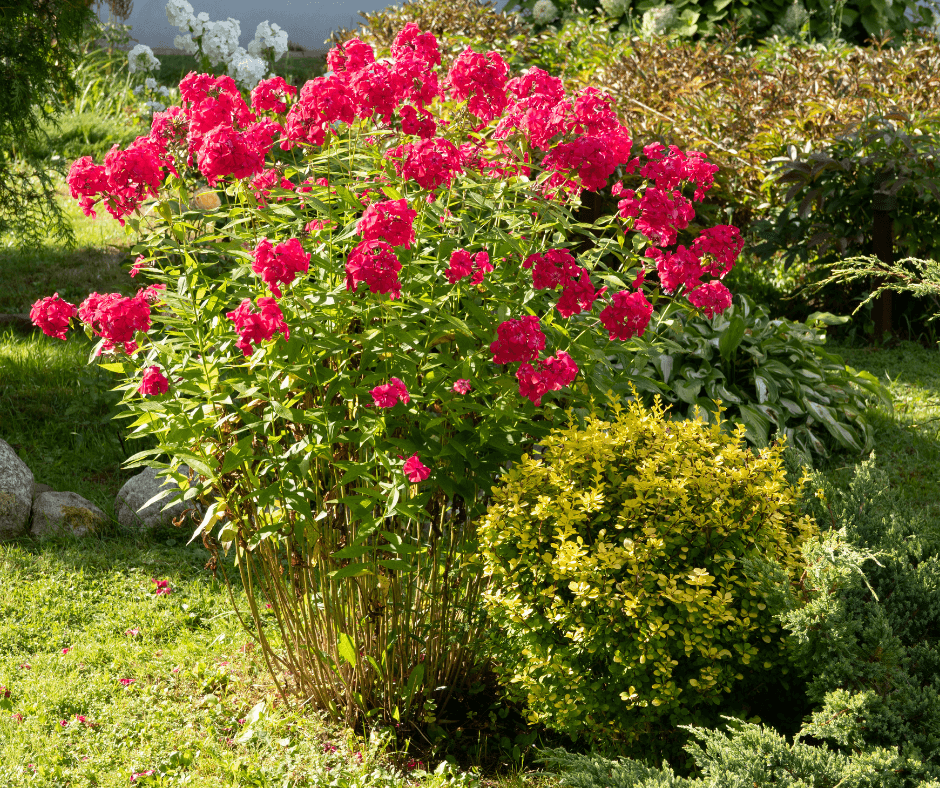

If your landscape is home to clump-forming or spreading perennials, like hostas (Hosta spp.), tall phlox (Phlox paniculata spp.), daylilies (Hemerocallis spp.), purple coneflowers (Echinacea purpurea), goldenrods (Solidago spp.), or perennial grasses that have been in place for several years, chances are some of them could stand to be divided. Sometimes the plants cry out for division by producing fewer flowers and appearing a little less vigorous than in prior years. At other times the opposite may be true—vigorous specimens that have outgrown their original spaces attempt garden domination by muscling aside other plants and creating congestion in formerly harmonious planting arrangements.

Dividing is the best way to deal with both situations and spring is a good time to think about doing so. Dividing in spring, when the shoots are emerging, is much easier than lifting and dividing large unwieldy specimens later in the season. Clumps of immature plants are also more forgiving and less impacted by transplant shock.

Why Don’t More People Divide Perennials?

Fear of killing plants is probably the primary reason, but it is unwarranted. The vast majority of perennials are amenable to division. A healthy plant, divided with even a modicum of care, will not die. In fact, the successful division of one moderately large clump is more than likely to result in two, three, or even four thriving new plants.

Dividing plants does not require much in the way of special tools: a sharp spade or garden fork, watering can, a garden knife or sharp trowel for smaller plants and a pair of gloves will do the job. To keep things tidy, consider working on a tarp when working with large clumps.

When it comes to division, water is your friend. If you can time the job so that it takes place a day or two after a rainy day, the ground will be soft and yielding, making it much easier to remove plants. If you can’t arrange that, water the ground around the plant thoroughly a day before you divide it.

Dividing Perennials in the Spring

Once the ground is soft in spring, use the spade or garden fork to dig down and around the clump until you can lift the root ball out of the surrounding earth.

Some species, like daylilies, can be divided by simply pulling apart the roots with your fingers. Others, like hostas (Hosta spp.), may require the use of a garden knife, spade, or garden fork. Depending on the size of the clump, you may be able to separate it into two, three, or even more divisions. No matter how many new plants you create, make sure that each division has a healthy supply of roots attached.

Once you have made the divisions, replant one of them in the old planting hole, improving the soil with a quality natural amendment, like Fafard Garden Manure Blend. Distribute the others to new locations around the garden, making sure that the young plants will enjoy the same light and soil conditions as the parent. Amend the soil as the divisions go in and water them regularly as they establish themselves, especially if the weather is dry.

If your garden is so full that you have to hang out the “no vacancy” sign, donate the divisions to family and friends, or local public gardens. If you can’t install the divisions right away, or are giving them to others, be sure to keep them cool and moist until they are ready to go into the ground. Planting them up in pots is another options.

Dividing Perennials in Fall

While spring is an excellent time to divide many perennials, early fall is also good. Stress on plants and humans increases as temperatures rise and rain amounts decline. Spring or fall conditions are more comfortable for the specimens being divided and the individuals doing the dividing.

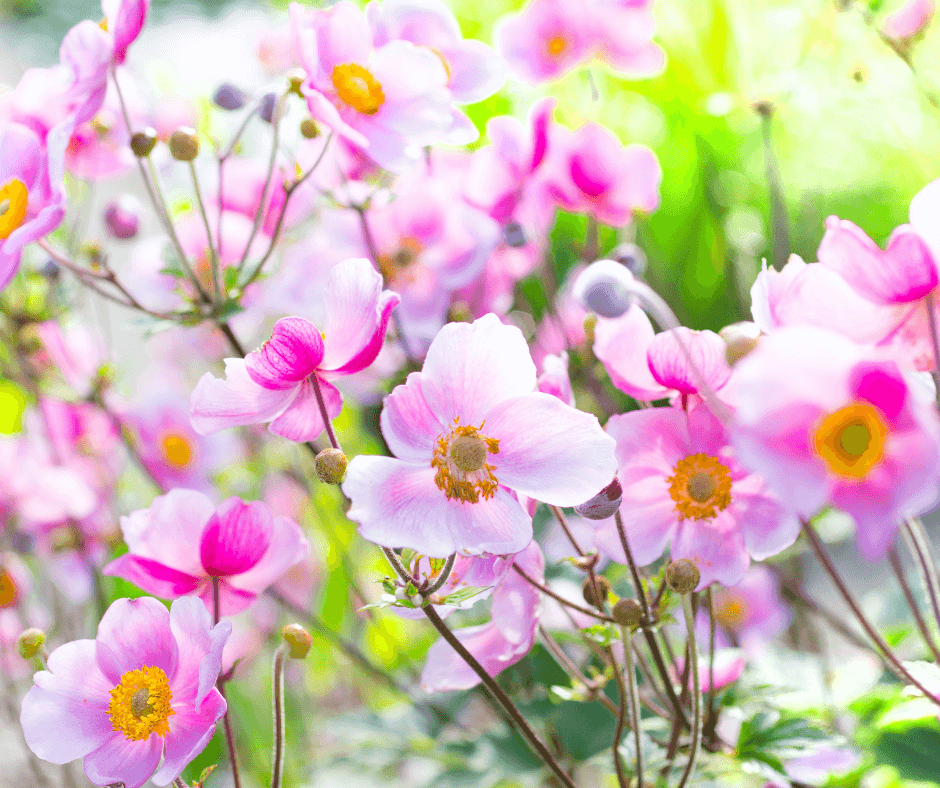

The common wisdom is that fall-blooming plants, like Japanese anemones (Anemone hupehensis var. japonica), asters (Symphyotrichum spp.), and goldenrods (Solidago spp.), should be divided in spring, and spring-blooming plants, like Siberian iris (Iris sibirica) and moss pink (Phlox subulata), should be divided in fall. As with many time-honored “rules”, there are exceptions. I make one for early spring bloomers, like snowdrops, grape hyacinths, and daffodils, dividing them right after they finish flowering, but before the foliage has withered. Since these plants are ephemeral and disappear for their annual siestas in late spring or early summer, it is a good idea to divide them while you can still see them.

Thrifty gardeners have always divided plants, gradually filling up their gardens with no additional investment, other than a little time and energy. Distributing divisions around the landscape also creates repetition, one of the key tenets of garden design.

With the renewed emphasis on sustainability, the age-old practice of multiplying by dividing has gained new currency. It links today’s gardens with the past and the future.