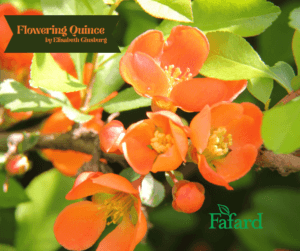

Every year I glory in the first signs of spring—snowdrops, crocuses, early daffodils and grape hyacinths. But the big show really takes off when the swollen buds on the old flowering quince start popping open, revealing joyful, pinky-white blossoms that cover the shrub in a foamy cascade.

The flowers are reminiscent of apple blossoms, which is no coincidence, since quinces and apples both belong to the larger Rosaceae or rose family.

Flowering quince—Chaenomeles japonica, Chaenomeles speciosa and hybrids—have been enchanting us for a long time. The japonica species was introduced to the United States from Asia in 1784, and the speciosa quinces arrived in 1815. They caught on quickly. For some time flowering quince was known as Pyrus japonica, a nod to the pear tree, also loved for its flowers, and known to its botanist friends by the species name Pyrus.

photo by Elisabeth Ginsburg

Japanese quince has many virtues, including vivid red-orange spring flowers, attractive ovoid leaves, and a relatively low-growing habit (two to three feet tall, and three to six feet wide). Densely branched, it also sports a highly effective system of defenses, in the form of inch-long spines. Harvesting branches for indoor display is a time-honored spring tradition, but requires sturdy gloves and a bit of caution.

The spiny trait is shared by the glorious Chaenomeles speciosa, a flowering quince native to parts of China, Tibet and Myanmar. It is larger than the speciosa type, growing six to ten feet tall and wide. The flowers are more red than orange and also open in the spring.

Orange and orange-red flowered quinces are show-stopping, but varieties with less flamboyant flower colors are also available. I love the old-fashioned hybrid, ‘Cameo’, with soft peach blooms and characteristic glossy green leaves on three to four-foot shrubs. The flowers are especially beautiful with the spring sunlight shining through them. If you are partial to white blooms, try ‘Jet Trail’, a somewhat smaller variety (three to four-foot height and spread) with single white petals surrounding golden stamens.

photo by Elisabeth Ginsburg

So what should you do if you covet the beauties of flowering quince but hesitate at the threat of thorns? Hybridizers have thought of that, crossing and back-crossing speciosa and japonica varieties to produce thornless cultivars like the trademarked Double Take series, speciosas hybridized by Dr. Thomas Ranney at North Carolina State University Extension Center. The color range includes ‘Double Take Scarlet’, ‘Double Take Orange’, ‘Double Take Peach’ and ‘Double Take Eternal White’.

Confusion can ensue when gardeners compare traditional flowering quinces against those of common quince (Cydonia oblonga) native to parts of Eurasia, which bears white or pink flowers. Common quince is grown primarily for its edible pear-like fruit, while the flowering species and hybrids, which may also bear somewhat smaller quantities of fruit, are grown almost exclusively for their ornamental value. Ripe quince fruits from either type of shrub exude an intoxicating fragrance, but cannot be eaten out of hand. Hard and sour when harvested, quince can be cooked down with a bit of sugar to make a lovely sauce or thickened further into membrillo (also known as quince paste or quince cheese) that is tasty when paired with cheese.

If you don’t want to worry about rock-hard quinces falling from your shrubs, opt for the Double Take varieties, which are both spineless and fruit-free.

Flowering quinces have long been prized as landscape shrubs. Twentieth century gardener and garden writer, Vita Sackville-West, co-creator of the great gardens at Sissinghurst in Kent, England, mentioned them many times in her garden columns for the Observer newspaper. She recommended using quince bushes en masse for flowering hedges. Needless to say, those hedges would be especially effective for use on property boundaries.

The shrubs can also be grown as specimen plants or incorporated into a mixed annual, perennial and shrub border. They appreciate the same conditions as other members of the rose family—full sun and rich, loamy soil, but can also adapt to light shade. Like many beautiful things, they tend to grow in an undisciplined manner. Prune after flowering to shape the plant and watch for root suckers. These are easy to remove, but if left unchecked will begin the process of turning your single quince into a quince thicket.

photo by Elisabeth Ginsburg

Glorious spring beauty is the best reason to invest in flowering quince. Don’t be intimidated by the spines. For centuries gardeners have grown all kinds of spiny things, including raspberries, barberries, cacti and holly, and managed, using a combination of gloves and caution, to enjoy them without drawing blood.